A Review of Don Mee Choi’s Freely Frayed,ᄏ=q, & Race=Nation

20.01.15

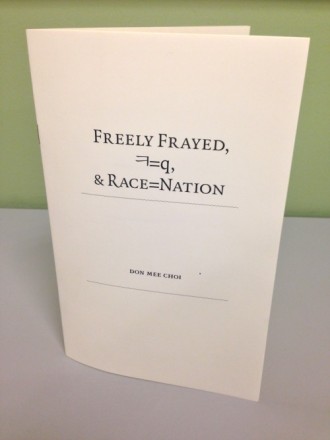

Freely Frayed, ᄏ=q, & Race=Nation

Don Mee Choi

Wave Books

18 pp.

“My intent is to expose what a neocolonial power does to its own, what it eats and shits. Kim Hyesoon’s poetry reveals this, which is why I translate her work.”

Don Mee Choi’s new pamphlet of talks on translation, race, and politics is a radical text, not because of the translation techniques she reveals (she doesn’t) but because of the political strategy she articulates. A Korean-born poet and artist who lives in Seattle, Choi has spent the last decade-and-a-half translating the work of major Korean poet Kim Hyesoon while working as an adult-ed instructor and writing her own complacency-dismantling poetry. In these three essays, she lays out the political motivation and context for her work.

The argument put forth in the essays is punchy, pungeant, and convincing: Korea, first a colony of imperial Japan, became a military outpost of the United States at midcentury. Having propped up various repressive regimes, the US maintains up to 100 military bases in South Korea and controls the South Korean military, keeping the entire nation on a warfooting to support its stance towards China and North Korea. Beyond its official military regime, the US has dismantled the domestic and agricultural economy of South Korea to create markets for its own industrial products, particularly meat. In these senses, South Korea is a ‘neocolony’ of the US.

The irreparable harm this does to the Korean landscape, psyche and bodies (especially female bodies) forms the subject matter, material and mise-en-scène of much of Kim and Choi’s work. In Kim’s work, this damage finds avatars in body after body—pig, rat, chicken, house, mountain, tear, hole. The neocolonial regime is inescapable and exacting: anything can be forced to have a body, register pain, eat, breed, issue more holes. In Don Mee Choi’s poetry, existence means enduring the relentless pressures of dislocation and disempowerment, migrancy and foreignness; these pressures induce a virtuosic text, by turns performing and refusing to perform fluency while weaving a fantastically frayed and glinting smart-fabric.

The three talks Choi collects here are radical not just in the contexts they claim or the political argument they sketch but also in the way they insist on the non-invisibility of the translator. The notion that a translator must make herself invisible in order to faithfully serve the translated text is in fact just an ideological canard meant to mask the fact that she is actually serving the dominant or imperial language into which she translates; we can recognize this when we recall the supposed praise that is awarded to a translation when the poem reads ‘as if it were written in English’. A new wave of translators—Don Mee Choi, Daniel Borzutzky, Carmen Giménez Smith, Sawako Nayasaku, Jeffrey Angles, Susan Bernofsky among others—are adamantly rejecting any such invisibility or service to the dominant culture. Instead, they take up an activist, non-invisible, very audible, assertive, even aggressive stance. In the essay “ㅋ=q”, collected here, Choi insists:

My translation intent has nothing to do with personal growth, intellectual exercise, or cultural exchange, which implies an equal standing of some sort. South Korea and the U.S. are not equal. I am not transnationally equal.

This insistent self-declaration on the part of Don Mee Choi is an act of anticolonial disobedience. It exerts itself all through these three essays—as when she insists that English-language readers’ tendency to read Kim’s work as political is the result of Choi’s own activist framing, thus completely rejecting and inverting the gendered expectation that the translator is a kind of handmaiden to the original text who must above all be faithful both to the text and the ‘original context’. In Choi’s view, thanks to US neocolonialism there is no ‘original context’ in Korea. In the essay “Race = Nation”, she observes that even at that ultimate site of origin, the moment of her birth, “Our race, our national identity, even our clothing [were] racialized and geopoliticized within the global class war. Therefore, when I was born in the tiny-roofed house, I was already geopolitically raced. Hence, me =gook.”

The ultimate force of Choi’s thinking lies in the counter-colonial model. Choi uses the term ‘twin-spirit’; one might apply the term ‘co-cuerpo,’ as coined by Heriberto Yepez or point towards the notion of the ‘deformation zone’ coined by Johannes Göransson and me. In every case, translation enacts a zone in which two supposedly separate bodies can possess and co-invent each other. It is just such a zone that Don Mee Choi’s own career configures—the twin-like, possessed co-body of her poetry and Kim Hyesoon’s, of translation and poetry, of forthright activism and service. This co-body, twin-spirit or deformation zone undermines the easily demarcated Enlightenment precinct of the individual man, the New Critical body of the individual text, the intellectual real estate of the individual genius. Instead something amorphous, powerful, undocumented, occult bubbles up. In the essays in this pamphlet and the prefaces and essays she’s published elsewhere, Don Mee Choi configures a counter-colonial co-body, an unknown zone, a zone made of ghost-twinship, translation, decomposition, trash and sound.

To translate is to be possessed, possessed by a twin spirit, a spirt of disobedience.[…] Because I am not Eternal, I scribble. Because I am not Overy, I scribble. Because I am not Anther, I scribble. Because I am not Petal, I scribble. Because I am not Beauty, I scribble. Scribble generic! O – rubbish!