A Cunny Poet’s Beautiful Book

31.07.14

Bunny Rogers’s Cunny Poem Vol. 1 functions as an archive — no poem has been omitted from those she wrote between 2012 and 2014, which were originally posted on her tumblr, http://cunny4.tumblr.com. All of these poems, from my very favorites to my least, are compelling and not easily grokked. A statement by Rogers in her 2013 interview with Harry Burke is perhaps a good starting point for approaching the book: “The coexistence of comedy and tragedy in all things is a foundational idea for me and thematically appears in the poetry.” Notice that she says “all” things, and a “coexistence,” not resolved, never concluded, settled, simplified.

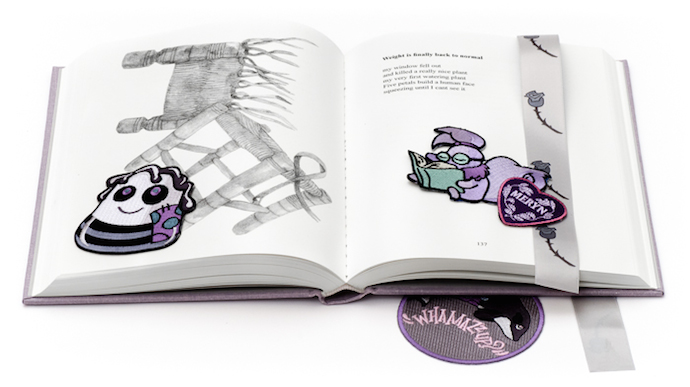

Likewise, Rogers’s poetry doesn’t become less complicated, uncanny, and striking as you begin to tease out its themes and techniques. Certainly the coexistence of comedy and tragedy is a theme overall, but there are also repeated references to addiction, imprisonment, safety, and death. And there are many symbols, both within the pages and also upon the included ribbon bookmark, emblazoned with roses from Clone High, a short-lived cartoon series whose love-lorn Joan of Arc clone character is part of Rogers’s gallery of heroes or icons (another is Elliott Smith, mentioned in a poem and gifted as one of several custom-made badges that come with the book). Also illustrating and accompanying these poems are drawings by Rogers’s close friend and collaborator Brigid Mason. Chairs, ribbons, and eyes recur in the artwork for the book as well as in Rogers’s visual artwork, for which she is well-known. My intuition is that these symbols, figures, and themes are like the careful decorations of an aesthetically and emotionally sensitive person’s childhood bedroom — she keeps close to her the people and things that feel resonant, expressive, right.

The poems themselves often employ a first-person speaking voice, which ranges from “like”-heavy casual speech to more formal pronouncements. Dark sarcasm and deadpan, ambiguous jokiness pervade the book, which is in keeping with the comedy/tragedy theme. There is something unnerving in these poems’ ambiguity of intent and meaning. Nothing is resolved, nothing is simply a joke or simply not, nothing is “honest” or means one stable thing. Rogers said, in the same 2013 Burke interview, that she doesn’t think she is or can be “honest,” only “accurate.”

What is Rogers accurate about? For one thing, her work is accurate in its portrayal of the confusing, frustrating, sick and degrading dynamic that can exist between heterosexual men and women. Rogers puts it most forcefully in the poem “@ one with the screaming in my head”: “Adorability is fuckability / because children are adorable / and men want to fuck children.” Elsewhere, she compares men to cops, those symbols of corrupt, abusive power, but then follows with three repetitions of the line “cuff me Im guilty.” This metaphor for heterosexual dynamics is both playful and not, a joke and not, at once a comedy and a tragedy.

Rogers is also accurate in her portrayal of mourning, of perpetual sadness, of being alone and thinking and feeling, in a prison of one’s own. There is no exit except through the ephemeral comforts, the sedative drugs, the ego-gratification of attention and sex. There is the sad victory of doing what you want, even though it will hurt some other people and some people won’t like it and some people won’t understand it. Rogers quips, “Guilt is doing what you want.” She says, “In the end you marry your illness.” This perspective on life, where the best course of action is still terrible, where nothing is perfect, only the best you could do, is not comforting, but it feels accurate to me. Rogers writes, in the last poem of the book, “Dewey,” that “You pick a god figure / You work with what u have / You sink and accept the sinking / You drive a car through a fence.” But the perspective shifts — the “you” of the poem, who thought she was being a cocky badass, who drinks in the drivers seat, who feels desired and clever, is in fact not the driver but the passenger, a “Passenger in a drivers seat.” The perspective shifts again — you watch yourself die on a television in a bar, and you judge yourself, you don’t like yourself, you’re dead. The book begins with defiance and ends with death. At first a disavowal, a pushing-away of the audience: “My Art sucks”; “I dont owe anybody anything!” — and, finally, violent closure: “You suck / You die.”

Given that Rogers is friends with Marie Calloway, that a paperback collection of poems is forthcoming from Civil Coping Mechanisms, that she has been published by Illuminati Girl Gang and has many friends in common with “Alt Lit”-associated people, she will perhaps inevitably be compared to other contemporary poets on the internet, especially those writing in first-person about their lives, a mode which is frequently (and reductively) called “confessional poetry.” Rogers’s poetry is not a face-value, sentimental, diaristic poetry, but neither is it primarily tongue-in-cheek, affect-heavy, wink-wink poetry — in that sense, she doesn’t wholly fit with much of Alt Lit or with the smart, chic, satirical poets with whom she’s read live in New York. Instead her poems feel simultaneously like spontaneous emissions from a linguistically fluid, clever, sensitive mind and like uncannily irreducible, finely crafted miniatures. Rogers has feelings, she has thoughts — and, to quote her again, “Like I always say Im too smart for this.”