Book Album Book: Angel of Death

10.01.19

Part 7, in which we are ruled by Water.[1] Previous installments can be found here. Read in any order.

Side 1.

We are in the Valley of Shadows, accompanied by fear and isolation. We walk, however, in palimpsest—our images transposed, crossing over one another. We have learned not to see those around us, others who walk paths that intersect ours. We have learned to call the path our own.

Songs remind us we are here together. Chan Marshall’s voice doubled and tripled, layered over itself, is an aural image for this palimpsest. We walk with ourselves. To sing a song again is to layer your voice in time.[2] The songs on Wanderer have travelled together for years, and the album is a collection of these songs’ performances. A private incantation made public.

One of the stories that has accrued around this record is that Marshall became so enamored of Rihanna’s “Stay” that she once sang it 14 times in a night out at Karaoke. There are moments on the record where we overhear every time Marshall has sung a line, or when a past iteration drifts into the song, as in the chanting phrases that visit the end of “Me Voy,” before we head into the “Wanderer/Exit” at the bottom of the album. Which takes us to the top and we do it again: “Wanderer” we.

Judee Sill’s Heart Food (1973) is an earlier book of shadows and light, where heavy layers of vocals cast a spell of protection about us. Whether Sill had comfort to spare goes without knowing, but not without giving. So an album might record, if not capture, an impossible gift. Cat Power has always been a spell drawing on impossible reserves, or has been since Moon Pix (1998), which is said to have been a shelter cycle from a dark night of the soul, a summoning and dispelling of demons. Its ostensibly belated[3] follow-up, The Covers Record (2000),[4] presented a brilliant interpreter of existing songs, as Marshall gave us again and again what we thought we already had, but knew in a moment we had only been waiting for. Each subsequent album added dimensions to Marshall’s powers, as her voice gained texture, her breath and phrasing gained nuance, her influences (and those she influenced) flowered. Only The Sun (2012) felt forced, though it too has mellowed and ripened with the years. While a second set of covers, Jukebox (2008), did not have the magic of the first set, it waits for us to find it, spilling over as it did into a third set (the folded-in EP on the second, bonus record that picks up where Marshall’s cover of Joni Mitchell’s “Blue” left off). The collection is too careful, too varied, too strong to file away. Each time it calls to us we look at the track list, try again to hear what it is telling us.[5]

Both of her covers albums include covers of her own songs, “Metal Heart” on the later and “In This Hole” on the earlier collection. These are revisitations not just of songs but of selves, not so much a reinhabitation as another voice, another track over the path. There is also a shared cover of “Naked, If I want to,” a tiny gem Marshall found in the Moby Grape catalog. The song appears as well on two original albums by the Grape, a 57-second version on the self-titled ’67 album, and a 51-second cut on ’68’s Wow. It’s a song that replayed itself in miniature over that Aquarian year, then grew into Marshall’s definitive 2:47 version in 2000, a signature rewritten at 2:37 in 2008. In both cases its echo wanes in time.

Wanderer, like Marshall’s career, and her voice, takes us places. Her voice is layered as well with the voices of others, and other songs. We are here and there, and there, and there.[6]

Like Blue, Wanderer is an album of loss that embraces being lost, though the latter may be a more final goodbye, the wake of death rather than the dream of departed love. But Blue is no less Wanderer’s ghost, and vice versa, a double shadow. Wanderer sings to (and with) itself while it sings with other albums. This is where its ambition is most evident, for Marshall is working at the level of the album. We are learning, again, that this is where she is at her best—whether the album is an explicit set of covers or a more subtle homage. Marshall has overtly embraced the Sowelo Rune, the S, as on the cover of The Sun. And she has more covertly (which hides the cover)[7] embodied the Ansuz, the A that looks like the figure of our F, and represents song, the word,[8] listening before speaking. Marshall listens as she sings, and this is the spell she casts: We hear the song move through her. It is her rare gift, her impossible, depthless reserve.

To make a record like this, one that brings you along, requires a generic sense of empathy, few moments that call too much attention to themselves, and general excellence. Ask Brian Eno, who theorized and practiced the art of ambient music these past 40 plus years. Wanderer is not an ambient album, but it agrees to be aural furniture, as Eno imagined, but with Marshall’s patient flair.[9] This is virtuosic music that makes room for you to do other things while you listen. It invites you to think along even if you aren’t thinking about the music. All the while it goes on taking itself seriously, without apology.

We need music right now that insists, proudly, without compromise or embarrassment, I’m a woman.[10] It’s not all we need, but we need it. Not because we need to make a big thing of women making music, but because we need to listen. It’s not women’s responsibility to heal us, but it is our responsibility to recognize where life comes from, and to respect the feminine energy that keeps us alive and makes us whole. “Woman” insists on this acknowledgement, this respect. Marshall draws from the power she feels in motherhood, just as she holds the arm of her guitar next to her son on the album cover, a gesture of protection and an offering.

Side 2.

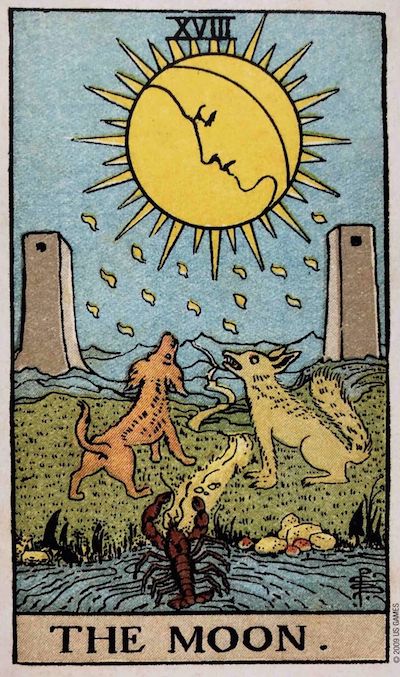

Every song is a cover, including her own. She summons herselves, waving them welcome before us, pantomiming their arrival from the portal on stage. Union Transfer, Philadelphia, December 15, 2018, on the half-veiled moon, one week before the 40th anniversary of Bernadette Mayer’s Midwinter Day.[11] On this night, familiar songs have new lyrics, and Marshall’s compositions blend and blur with those of others. She calls the spirit of Nico taking Jackson Browne’s “These Days” as her own, only to mix it with Marshall’s own song. We are gifted with a midset re-envisioning of “Horizon,” positioned as on the record, at the edge of one side, now cleared of studio affect. She floats along the front of the stage in a black dress, red-lit and beaming power. She closes the set by thanking her departing musicians, retaining the guitarist to perform a looping riff from “The Moon,”[12] which has its lyrics transmuted into rainfall and glow, then whispers goodnight to the fortunate crowd. We run off under the waxing, actual moon.

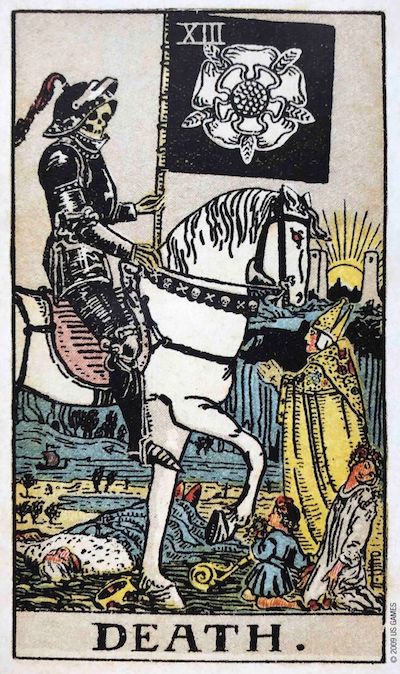

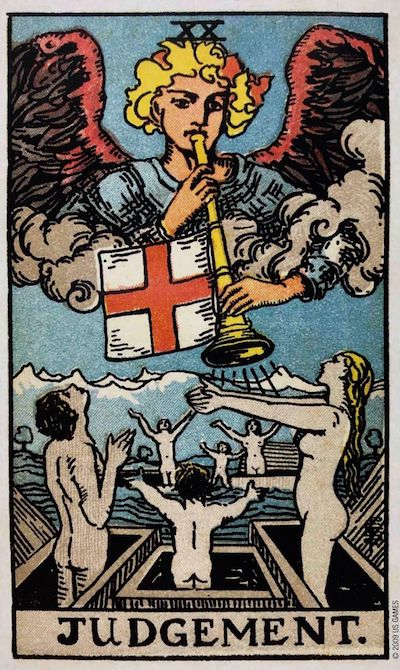

[1] Which is to say we are governed by The Moon, under the sign of Cups, though we have come to associate Cat Power with the Queen of Wands, and vice versa. So we wander as well under the Fire sign.

[2] As on “Black,” where the layered phrase Angel of Death appears over the start of the track, a choir of shadows that do not cross the lyric sheet.

[3] Seldom does an album appear before its time, even if it takes us a minute to catch up with it. More often, albums are delayed by the machinations of commerce.

[4] Is it possible we had trouble waiting two years after such a rich offering? And yet we recall this cultural impatience, the anticipation garnered by attention, Marshall having emerged from the foliage on the Moon Pix cover: Oh hey, it’s me—did you know you were waiting?

[5] It’s a good moment to revisit Marshall’s fitting tribute (and sole debut original on the album), “Hey Aretha, Sing One for Me,” and to then put on Franklin’s Amazing Grace, the title song to which Marshall offers profound respect in her fantastic chronological survey of transformative singers and songs along her way, in the poorly named interview feature, “The Music That Made Cat Power’s Chan Marshall.” A slight improvement might be “The Music That Made Chan Marshall Cat Power,” though of course it is more accurate to say Cat Power is Chan Marshall.

[6] This is Book Album Book’s refrain, as the portal of song takes us all over the world.

[7] Covert, in its adjectival form, draws etymologically from cover, as in shelter and hide.

[8] and comes from the Old Norse word for answer (per Runes scholar Kaedrich Olsen), which Marshall activates in the spirit of answer song

[9] There is a restless moment at the end of side one where Autotune appears on “Horizon,” and temporarily breaks the spell. We turn the record in hopes we can shake the effect.

[10] And this identity needs to be available to all who claim it.

[11] On and about December 22, 1978, Mayer wrote the long poem Midwinter Day, which would be celebrated in Philadelphia and several other cities on December 22, 2018 with durational, choral readings of the poem.

[12] The second song on the second side of the miraculous 2006 album The Greatest, which grapples with personal ambition while extending that ambition, a post-indie-rock feat if ever there was one. As Bill Callahan sang under his (smog) moniker, The champ always fights themself. As Rocky Balboa tells Adonis Creed in Creed (as we recall): See that guy there in the mirror? That’s who you’re fighting. I’ll leave you two alone.