Kafka on the Skin

29.05.18

Falling in Love

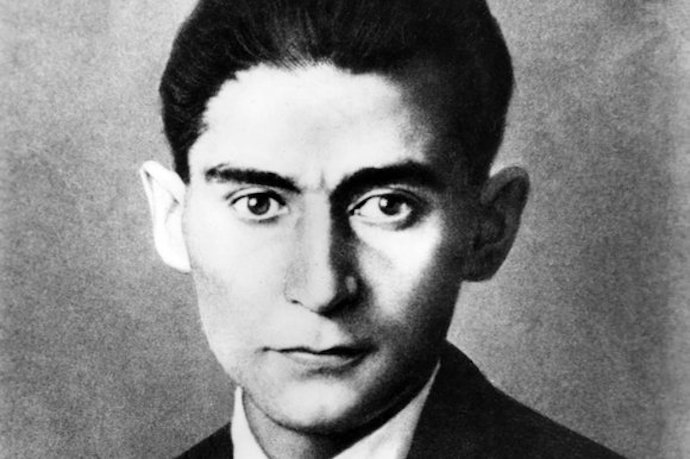

I don’t remember the first time I encountered Kafka. Probably my parents or New York grandparents had him on their shelves, tucked near the Mark Twain and Vonnegut. Maybe I brushed up against him later in one of the used bookstores I frequented with my dad. Wherever it was, I remember knowing his face before his writing. The emaciated Jew with the jutting ears and eyes of nervous prey, the haunted and hundred-yard star of the solider. Like Poe, the handful of Kafka pictures all hold a dark echo in the eyes. They were portraits of someone who will soon be murdered and knows it, or is being murdered with every breath, or is themselves a murderer. You see those eyes and you either turn away or you grab the book.

I devoured his writing. The stories, the novels. Maybe I read him at too tender an age but I got it. How we’re all alone. Trapped. And that thing he said over and over, his relentless truth: no answers exist save for the fact that there are none: Behind every door is another door, another sentry guarding it, bigger than the last, more impossible to move past. Life is a pointless maze with no center.

As as an angsty teen, who smoked too much pot and listened to Joy Division and early Pink Floyd, Franz’s worldview checked out. Like some twisted cosmic blues riff, Kafka didn’t make me feel better. He made feeling worse feel sublime.

Penetration

A decade later in Prague, Kafka’s city, I met a tattoo artist at the Thirsty Dog bar. Milos smelled of cheap Czech cigarettes and the crackling leather he wore from collar to toe. Except for his moon-shaped face, hardly an inch of his exposed skin stood uninked. His handshake was a bear trap even as his eyes caught and released me in a glance—American expats were a common sight in ’92. Rumor was, there were more than 15,000 of us living in that cheap-beered paradise unregistered.

We small talked a bit, our words barely outshouting the music. I told him I was just passing through, gave him some of the highlights of my backpacking odyssey. He asked about the States. He talked about life under the Soviets. I praised his ink, especially a Japanese carp that circled his wrist. “Self-done,” he said.

I showed him the postcard I’d been carrying since I’d arrived in Prague. It was a photo of a Kafka mural the Communists had effaced. A glaring Kafka surrounded by the grotesquely rendered inventions of his mind. I pointed to the center.

“Can you do this?” I said. “Just the Kafka part?”

When Milos finally understood I wanted Kafka tattooed, he embraced me. He roared in my ear: “These stupid Czech kids, they only desire garbage American flash: flaming skulls and tribal stripes,” he said. “But you, my friend, you want symbol of Prague.”

Two hours later I had the symbol of Prague on my right leg, five inches above my ankle. Milos rendered it perfectly and lovingly, in simple tattoo black.

For years, I hardly gave the tattoo a thought. We get tattoos for ourselves and then, mostly, forget them. They’re part of us, like a foot or a finger. A metaphor drawn into the flesh we live inside every day, they become a thing largely for others. I’d let people guess at the face on my leg and almost no one got it right. Eddie Munster and Mr. Spock were standard misses. It’s the ears, I suppose. They’re caricatured slightly. I’d laugh at their misfires. Then solemnly pronounce Kafka’s name. Like it was a password into a secret club.

Delusion

Years later I had a blazing moment of doubt. Tripping on shrooms and in a maudlin mood, twisting in my bed sheets, trying to sleep, my mind filled with the lightning storms of thought that sometimes prevented it from shutting off when I tripped. There flashed a sudden and obvious connection I’d never made. What I call a “stupid epiphany” surfaced in my gyrating head.

In Kafka’s story, “In the Penal Colony,” the unlucky prisoners are essentially tattooed to death, their crimes inscribed into their skin by a “remarkable piece of apparatus” until they die.

Was Kafka my crime?

Within my psilocybin swirl it seemed he was both crime and sentence. I’d given myself a harsh one born from an impulsive choice. I’d been charmed by the city and the charismatic, bear-like Milos. I’d been haunted by the castle on the hill; the castle that towered like a titan’s helmet, visible everywhere, seeing everything. It loomed over Kafka’s tiny house. It shadowed his imagination like his work had shadowed mine.

Staring at Kafka’s face, demonic in the moonlight, I knew what I had to do.

Breaking Up

In Bulgaria I’d made friends with a tattoo artist who’d studied as an icon painter. His tattoos possessed a hybrid swirl of religion and punk rock, delicate shading and swirling lines, unlike anything I’d seen. I trusted him and he liked my idea to “lighten up” the Kafka, injecting a bit of levity into the piece.

The portrait of the author would be unchanged, but on the other side of the leg we’d put a cockroach, done in the same graphic style but with color, the brightest red we could find. A red circle would encase Kafka and a black one, the same tattoo black Kafka had been inked in, would circle the cockroach, with smaller circles connecting the two around my shin and calf: thought bubbles. It was a play on the old Zen parable by Chuang Tzu, the man who dreams of being a butterfly but is never certain whether he is, in fact, a man or just a butterfly dreaming he’s a man. Kafka would dream of the cockroach; the cockroach would dream of Kafka.

When people say tattoos are dangerous they’re usually talking about the needles and the dangers of infection. But most tattoo artists are as careful as surgeons with sterilization. Turns out there are other things that can go wrong. The bright pigments have metals, and I chose the brightest shade of red I could find: shrieking, neon coquelicot. Only after my leg swelled to twice its normal size did my friend remember we should have done a test patch behind my ear to see how my skin reacted to the ink.

The pain was excruciating, ten times what I’d experienced from the original tattoo. Every step felt like the Russian version of the Little Mermaid. My calf started to resemble a thigh.

At the hospital, the nurse screamed at me, and my wife translated as fast as she could, “You kids are idiots…you’ll lose your leg…are you stupid?” I rolled my eyes and thanked her for the antibiotic script. She was out of touch, I thought, from a generation that couldn’t even begin to conceive why “young people these days” would want to adorn their bodies with ink. In Bulgaria, before, only sailors and criminals got tattooed, not professors of literature. Not writers.

Only later did I understand the nurse had been talking facts. If the body rejects the ink there’s sometimes nothing to be done. The ink is in the skin. Only surgery can remove it and, if necessary, amputation.

Resignation

I don’t think much about the tattoo anymore. It’s for others again. I take the leg I almost lost for granted.

Occasionally I use it as a visual stunt in the literature classes I teach, a prop to convey the magic of ink, on the page and the flesh. We discuss “The Hunger Artist,” then I slap my foot on the desk and roll up my pants leg. Ta-da.

“You see how much I love literature? Enough to put it on my skin. Permanently.”

I joke how I “stand on the shoulders of giants.”

Kafka would have loathed the cheap theatrics, just as he almost certainly would have despised his face on my leg. He didn’t want any record left behind. His widely known last request was for his best friend, Max Brod, to burn what remained, unread.

I’m certain Franz would have preferred me losing the leg and not only because it would have meant the effacement of his image. Loss of limb is a better ending. It’s more absurd. More Kafkaesque.