Welcome to the Predatorium (or Kim Dorland’s Creepy Copse)

25.04.11

Welcome to Predatorium, the most exciting paintball experience ever.

Welcome to Predatorium, the most exciting paintball experience ever.

In Predatorium, you will hunt the most terrifying monsters; in turn, you will be hunted.

Hunt and be hunted! Predatorium immerses you, the player, in a weird woods, a creepy copse crawling with macabre creatures and famous monsters from horror films. Also, it’s art!

Predatorium isn’t real, not really. It’s an idea I dreamed up in Kim Dorland’s studio. The studio’s in Toronto’s west end; beside it, there’s a professional paintball course where policemen train. I saw the studio, I saw the course, and I decided that the studio would be way better for paintball. It’s splattered with paint. It’s packed with theatrical paintings and sculptures. A lot of the paintings are of woods, so it’s already sort of a woodsball course: would-be woodsball. Paint, predation, and the supernatural – these themes haunt Dorland and the world his work creates. I have decided what to call this world: Predatorium.

Predatorium Rules:

Rule #1: White shoes: don’t wear them.

Rule #2: Bring your own paint gun. Bring a regulation paintball gun. Bring a water pistol filled with paint. It doesn’t matter which. You’re going to lose.

Rule #3: Bring your own paintballs. Blaze orange works well; neon pinks and greens do, too. Glow-in-the-dark paintballs are great: buy either Kryptonite or Diablo Dark Legion. It doesn’t matter which. You’ll lose.

Rule #4: Bring teams or play solo: it doesn’t matter, you’ll lose. If you are wounded, raise your hands above your head; the Dead Man Silent rule is in effect. If you are dead, raise your hands about your head and go lie down; the Dead Man Zone rule is in effect. If you want to purchase a piece of art, fire at it. A blue mark means it’s on hold for you. A red mark means it’s yours.

Rule #5: Shooting other players is allowed. Shooting yourself is allowed.

Rule #5: Shooting other players is allowed. Shooting yourself is allowed.

Rule #6: There is no referee.

In Predatorium, the goal is to go through an increasingly dark world where you will be confronted with increasingly monstrous monsters. There are three levels; each represents a period of Dorland’s artistic output.

Level One is early work. Level Two is later work. Level Three, the last level, is the darkest. It consists of paintings and sculptures from Nocturne, Dorland’s newest show. In Nocturne:

There are ghoulish green rabbits.

There are owls. They burst off canvases in gooey globs of paint, beasts of blasted beauty.

There’s an owl, a stuffed owl whose feathers have been silvered, then plastered with phosphorescent paint. Is this what happens when owls eat green rabbits?

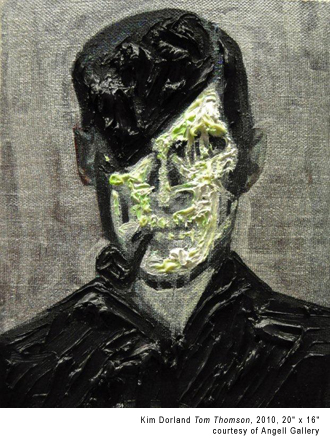

There’s Tom Thomson. He’s posing in a portrait Dorland composed on an iPad. For a face he has a skull, a green glowing skull. He also appears in a painting; at least, his skull does. It’s lying amid the duff of a forest floor.

There’s a ghost. It’s glowing: is it ectoplasm, or energy? It’s a dollar-store skull draped with what look like lengths of luminous cloth. The cloth isn’t cloth: Dorland poured phosphorescent paint and an acrylic called liquid mirror onto plastic sheets, then peeled them off in long strips after they’d dried.

Rule #7: In paintball, paint is death; in Predatorium, Death is paint.

Predatorium opens with Level One, a selection of Dorland’s paintings from roughly 2000 to 2005. Woods are present in almost all the works; sometimes teens are hanging out in them. Sometimes Lori, Dorland’s wife, is there. Sometimes, deer.

Predatorium opens with Level One, a selection of Dorland’s paintings from roughly 2000 to 2005. Woods are present in almost all the works; sometimes teens are hanging out in them. Sometimes Lori, Dorland’s wife, is there. Sometimes, deer.

Rule #8: Don’t shoot Lori. She comes back in later levels, and she is fucking scary.

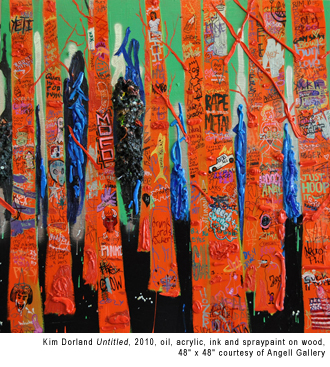

In Level One, the trees are painted; that is, not only has Dorland painted pictures of trees, but the trees that he’s painted seem to have been previously painted on. This is realism: in the real world, trees get painted on all the time. Painted on and carved up: these are the ways in which hunters blaze trails, making wild woods their own.

A player in Predatorium must master the tricks of the trail:

Flagging: Hunters tie bright bits of cloth around branches and trunks. This is the worst way to blaze a trail. Cloth falls off. Weather wears it out.

Carving: Hunters carve notches into trees. Sometimes hunters will carve off bark, then paint the bald spot. Carving into a tree makes it susceptible to disease. Painting a notch makes it look like it’s bleeding.

Painting: Hunters paint slashes of colour on trees. Vertical, diagonal, horizontal: it doesn’t matter. A cross. An X. Paint should be strong enough to weather severe cold and heat, to withstand rain. In the past, hunters employed paint that contained lead and toxic solvents. It poisoned flora and fauna. Guns kill animals; paint kills it all.

Many players will be tempted to blaze themselves a trail through these woods. Do it, don’t do it; doesn’t matter. When all the paintings feature blazes, how will a blaze stand out? The people in the paintings have a similar problem. They’re in woods in which each tree has been blazed with paint and carved up with graffiti. Turn this way: There’s an orange-slashed tree that says OZZY. Turn that way: There’s an orange-slashed tree that says OZZY. They’re in a labyrinth, as are you.

Many players will be tempted to blaze themselves a trail through these woods. Do it, don’t do it; doesn’t matter. When all the paintings feature blazes, how will a blaze stand out? The people in the paintings have a similar problem. They’re in woods in which each tree has been blazed with paint and carved up with graffiti. Turn this way: There’s an orange-slashed tree that says OZZY. Turn that way: There’s an orange-slashed tree that says OZZY. They’re in a labyrinth, as are you.

You’re lost.

Cones and rods.

The eyes of animals aren’t like ours. In the woods, animals see blue as something alarming. Hunters don’t wear blue jeans. Hunters don’t blaze trees with the colour blue.

Wear jeans if you want, player. Hunters are afraid of frightening off deer and moose. The things that are hunting you aren’t afraid of anything, let alone what you’re wearing.

Wear red – it’s retro. In the old days, hunters carried pots of red paint and brushes into the woods when they blazed trails. Some had paint markers, trigger-pull apparatuses that screwed onto cans of paint. They wore red vests and coats. That was as bright as they could be.

Wear orange blaze. In the 1950s, hunters got a gift: spray paint cans came along. Shortly after that, Day-Glo came along, too: hues that were brighter than any in nature. Orange blaze became the colour by which hunters recognized other hunters, and protected themselves from each other. They blazed with it. They wore clothes dyed with it. They daubed the shade onto their guns. Farmers wrote with it: they slapped the word COW onto their cows.

In Level Two of Predatorium, it’s not the hunters who wear orange blaze; it’s the woods.

In Level Two of Predatorium, it’s not the hunters who wear orange blaze; it’s the woods.

Level Two consists of paintings Dorland did after 2005 or so. They’re distinguished by crazy colours and crazy creatures.

Pink, green, blue, orange – the level is dominated by neon tones. In some paintings, there are neon slashes on trees; in others, entire trees are neon. The earth is neon. The sky is neon.

Why would the woods go Day-Glo?

The trail is tricking the hunters.

Where the world is awash in orange blaze, hunters are bound to shoot other hunters.

In these woods, people aren’t simply wearing orange blaze: they’re made of it. Faces and bodies composed of neon slashes. As if people are nothing more than trail-marked trees.

A portrait of Lori doesn’t look like her, or anyone. It’s pounds of paint piled on top of pounds of paint. Some of the squiggles look like maggots, some like worms. Is she decomposing, or in the process of becoming composed? Is putrefaction impasto?

Tom Thomson, rest in paint.

The unnatural world has usurped the natural. In the natural world, in the woods, paint plots out a path of predation; in the unnatural world, in these woods, predation is paint, and it manifests itself as monstrousness.

Predators prowl through Level Two: growling wolves, wild owls, vicious ravens.

Predators prowl through Level Two: growling wolves, wild owls, vicious ravens.

An owl is bulging from a canvas. Its body is about the size of an actual owl’s. It’s paint: tube upon tube of black paint piled up to approximate a bird. Only the outermost layer of paint has cured. A thin skin: beneath it is glopping guts.

Life-size, these owls are like nothing in life, and they’re sort of corporeal: flesh and blood, or in this instance, paint and more paint. They are forcing their way into the world and they’re fucked up: fighting to take form and fighting to destroy form.

If you think that the familiar woodland creatures are deformed and frightening, you should see the supernatural spectres. The boogeyman is screaming. Bigfoot has rhinestones for eyes. Jason looms above it all. Jason Voorhees, the villain from the Friday the 13th film franchise.

Shoot them. Hitting them won’t help. How can you kill painted monsters with paint? More paint only makes them more powerful.

In Nightmare on Elm Street, in order to make his way out of dreams, Freddy must penetrate the skin of the world.

In one scene, the skin is a bedsheet: he rises up under it, but doesn’t break through. In another scene, it’s a bedroom wall: when he pushes against it, it stretches like it’s elastic.

That’s what it’s like in Predatorium. The predators are trying to leap from the paintings and into life, or what we call life. The trees are, too. It’s like that scene in Evil Dead, with the branches that grab the girl.

It’s like Dorland’s ideas of nature come from horror movies. More than that: it’s like they come from watching horror movies on a VCR in a rec-room in Alberta in the 1970s. The work flirts with a rec-room aesthetic. Look at his use of rhinestone eyes for owls: very macramé. Look at use of nails and string for the wolves’ teeth and drool: very string art. Look at the trees: they’re painted on wood, so that grain is visible beneath. Is it wood paneling?

Look at the glitter.

Taxidermy is another art form favoured in rec-rooms; it appears in the last levels of Predatorium, too.

Taxidermy is another art form favoured in rec-rooms; it appears in the last levels of Predatorium, too.

There’s a lynx’s head nailed to a board. Green paint drips from its forehead to the floor.

There’s a timber wolf mounted on a wood platform. Its fur’s been coated with pink and purple paint. The wolf’s wet as a paint brush. The wolf’s a paint brush. Who heard of a pink and purple gray wolf?

Many of these pieces come from New Material, a show Dorland did in New York in 2010. They act as a counterpoint to the paintings: they’re natural, while the predators in the paintings are supernatural; they’re dead, while the predators in the paintings are deadly. What killed them? Did players pelt them with paintballs?

Perhaps the predators are evolving, or devolving, into paint. Perhaps paint is preying on them. Paint seems psychopathic. It has a mind of its own; or, better yet, it had a mind of its own and then and lost it.

Paint has paint for brains.

–––––––––––

see more from Derek McCormack on Fanzine here. And see his website (if you haven’t read his books, oh boy what are you waiting for… get your grab bag, ’cause it’s a treat.)