Super Neutral

24.02.14

Whether it’s the music, technology, social politics or environmentalism, one thing is clear: people seem to think they’ve pinned down exactly what the Pacific Northwest is all about. Secret bands! Microsoft! Legal weed! Evergreens! As a native it’s become less than appealing, more than annoying. We are OK, it’s true. And perhaps we do deserve something: a functional cultural landscape, a growing economy, tolerable forms of reason (to name a few examples). But we already have these things, because we desire them and work to make them reality. The praise is merely a distraction. Maybe it’s a lack of bravado, but praise is not something we’ve been like to indulge. Especially in the case of sports.

Days before Super Bowl XXLVIII, Ken Jennings, the Seattle-based software engineer turned infamous Jeopardy! phenomenon wrote a somewhat glossy rumination on Northwest sports fandom. Like me, Jennings grew up under the darkened specter of constant cloudcover, a darkness both weather and franchise-induced. He is right to point out the facts: the Northwest has never been a dominant locale for national championships; we lost the Supersonics; the Storm are highly under-appreciated; and one more thing: in the cracks there have been moments of possibility. In Jennings’ piece he likens these recurring glimmers to sunbreaks, a term used liberally by meteorologists in the dreary months of fall-winter-spring to announce the chance of a pause in the drizzle. We permit these heady forecasts under the ever present certainty of what’s expected, accepted: gloom. We’ve become the kind of people who savor the chance of a pause, never mind a true clearing, and that is either an impasse or a virtue, depending on how you look at it.

But Jennings would only go so far, and maybe that’s the point. His piece seems to embody the very essence of our geographical ethos: when it comes to sports, we’ve grown painfully neutral, if not despondent. This is because we know better. For those of us who dare to lend an ear at all, we surely don’t hope. We don’t dare venture outside our better judgment to expect change, or further yet, success. We’re far too aware of the past to defy the only set of logic we’ve been equipped with, and we’re highly suspect of an uneducated lean toward positivity. Jennings is talking through a familiar mouthpiece when he expresses gratitude toward what we already have, romanticizing sunbreaks. It’s always easy to do so when your audience is content to buy sunglasses yearly.

I surely can’t be talking about Seahawks fans, can I? The 12th man? I absolutely am. Pragmatism, in the form of a spectator, comes with some level of expectation, even if that expectation is a long-shot. Northwest fans are not pragmatic. We are realistic. Even when the odds are in our favor, we’re a far cry from confident. We are chronic underdogs. We expect the cave to eventually collapse, daring only to squint if we will at the point of light in the distance before all that hollow air we foolishly called hope vanishes, choked off from the outer world. In here it is dark, indeed. Seahawks fans, under all their newfound glory, are Northwest sports fans after all.

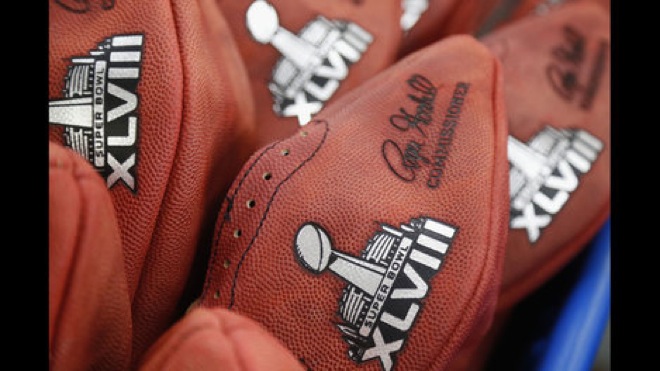

I watched the Seahawks play in their first Super Bowl as a gangly freshman at the University of Washington, in Seattle. The game was officiated poorly, outrageously (as those in the dorm around me echoed), and fit quite neatly into our blunderbuss narrative. I became naive for a short time that season, seduced by probability and momentum, only to learn what I already knew: disappointment. The process left me disgusted. That disgust was so supreme, in fact, that I refused to pay attention to any sports whatsoever for the next seven years. I had cared one too many times. Which brings us to the matter at hand: the title of Super Bowl XLVIII Champions. But first a parallel.

I had the rare opportunity that week to watch my favorite band play live, just five days before Seattle won its first national title. Many of us have seen our favorite band play, even if we aren’t show-going types; when we go, we see our favorites. This was a different case entirely. Neutral Milk Hotel sprung into public consciousness almost as quickly as it disassembled, and if you didn’t have your ear to the rails, you would have missed them completely. Or at least you would’ve missed them play live. I was introduced to the music through my older brother when I was sixteen, just five years after the band had fallen into public obscurity, and just as the cult following it since developed was coming into focus. Even then, upon first listen, my chance to see these songs performed was out of question, merely a detail that failed to discourage.

Super Bowl XLVIII didn’t look much different than that first Super Bowl we played, back in early 2006. We were crowd favorites, suspected to perform consistent to our merits, and unanimously chosen by commentators to seal the deal. Everything was working, everything was set. But that’s precisely the moment things become toxic. That’s precisely how you fall into the snare of hope and end up smothered under a pile of collapsed dreams, whispering those words you’ve whispered far too often: “Never again. I mean it this time. Never again.” Along with every #12 this side of San Francisco, I had my doubts, because I know better.

As the band took the stage I gasped, started crying; a fay, sheepish set of open-eye tears I can only describe as those of an Olympian whose life pursuit had finally come to fruition. It was a cry I’d never experienced, shed through a foreign conduit of disbelief and pure joy. It was in this same moment, though, that I realized how much of my admiration stemmed from the impossibility of this very moment’s materialization, a mystique that could’ve lived indefinitely through me, supplied me with a meaning I could always call my own. Was I throwing that away? I was fine the way things were, right? Growing up in the Northwest had not only instilled the ability to accept hard truths like these gracefully, through the reality of sports fandom, but the ability to nearly enjoy them. This is how we’ve learned to function: on limitation, and the resolution of such limitation’s continuity.

I again became aware of this new emotion five days later, just after the kickoff in the second half of Super Bowl XLVIII. Percy Harvin, who had been sidelined due to injury for all but a few plays of the regular season, ran the kickoff back 87 yards for a touchdown. The scoreboard suddenly read 29-0 in favor of the Seahawks, with less than half the game remaining. An inconceivable obstacle for Denver. Still, I would not allow myself to celebrate. I patiently awaited a turn in momentum, a mistake, a capitalization. Somehow, even through historical precedence, we would find a way to lose this game. This was all I could think as I bore witness to an astounding performance by my own team. When is it all going to fall apart? There was no instrument to register joy. I had never created one. In disbelief, I watched as the Seahawks continued to dominate on both ends of the field. It didn’t seem real. Are we allowed to win the game?

Halfway through the set, Jeff Mangum, frontman of Neutral Milk Hotel asked the audience to indulge a request of his. “If you could please put away your phones and cameras for just one song, let us exist in this moment together. Let’s be present here in this space.” The plea came off a bit stilted. For one, I had never been told how to experience their music. Until then it had been mine. For most in the crowd, this was one of the bigger events in their musical lives, if not their life. This was the Super Bowl of nostalgia, in my eyes, and I was winning. I wanted to take a video. Reluctantly, I put away my phone knowing Jeff’s suggestion lay a cage around something I’d owned for more than ten years. The song was spectacular, it couldn’t have been performed better, but somehow I began feeling like I had given up a critical part of myself by experiencing it.

Near the end of the third quarter I became greedy. All those years of hard luck started bubbling up in a selfish, haughty rage. Bearing down on their first points of the game, I salivated over the thought of another Denver turnover, another improbable break in Peyton Manning’s #1 offense. We can’t let them score, not even once, I thought. We need a shutout. Winning had already become routine, already a right more naturally ours than the rain. Of course they did score, completing a pass through obvious defensive interference, and successfully made the two-point conversion on top of that. Did it matter? In the outcome of the game, not at all, but it did reveal the addictive power of success.

Later on in the set I pulled out my phone. The band was finishing up “Untitled”, an instrumental segue into my favorite song, Two-Headed Boy part 2. When I tapped Record I felt no remorse. For all those years, I had waited without waiting, wondered without believing, and the moment had actually come. But somehow I wanted more. I wanted a piece for myself. The crowd roared as the last chord rang out, and as I pressed Stop, I almost knew the video hadn’t taken. It couldn’t have. Maybe the memory had run out. Maybe I’d never pressed Record at all. But no. The video saved, locked tight in my phone, and I slipped it into my pocket smiling.

Some things are better left alone if you ask me. I’m glad the Seahawks won. I’m glad I got to see Neutral Milk Hotel live. These are things I can enjoy at least remotely. But I’m not about to believe anything has changed—other than my expectations—which now, surely, will not be realistic.

As Jeff left the stage I pictured that sixteen year-old version of me, so willing to commit obsessively to a band that showed no sign of producing music again, let alone performing the music they’d already created. What I had had was enough, yet somehow, years and years later, beyond my wildest suspicions, they resurfaced to turn that doubt into a miracle. But had I ever wanted them to? Had I ever needed them to?

In the final minutes of the game I started to empathize with the Broncos’ long faces. The guys on the field had visibly surrendered after their first fruitless drive of the fourth quarter. There was nothing they could do. The fans were in the same boat, and a lot of them had spent a fortune on tickets (womp womp). Countless droves across the nation were likely watching in disbelief of a different kind, a more familiar, terrible kind. Each time we prevailed in that final quarter, adding insult to injury, I cowered shamefully, knowing so well the sting on the opposite side of history. It’s all I had ever known. It’s all I had ever expected. And like anything lost, I began to crave it.