Digging for Dirt: The Life and Death of ODB

25.11.08

Digging for Dirt: The Life and Death of ODB

by Jamie Lowe

published November 25, 2008

Faber and Faber

hardcover, 288 pgs.

I get Jamie Lowe’s new book, Digging for Dirt: The Life and Death of ODB, and first thing I do is flip to the inside back cover. Not out of any sort of subconscious pre-judgmental desire for journalistic authenticity in this biography of one of hip-hop’s most enigmatic tragic-comic figures. But studying Ms. Lowe’s portrait and bio, what strikes me most is not that she’s a white girl wearing what appears to be a kimono with Mesopatamian accents, but the fleeting idea that Tammi Littlenut had written a book, the one I’m holding here about Ol’ Dirty Bastard.

See, I’ve had this secret crush on Tammy Littlenut from Strangers with Candy since I first saw the episode when she and Jeri (Amy Sedaris) were supposed to take care of their five pound sugar sack of a baby, and Tammi Littlenut ends up with all the responsibility and eventually ends the episode with her, Chuck Noblet (Steven Colbert), and Mr. Jellineck (Paul Dinello) jumping on the bed in a motel room. I had a few things going in my favor following the initial impression of Ms. Lowe’s picture: Fantastic red hair? Check, even though her picture is in black and white. Lives in Brooklyn? Check, my roommate had spied Tammi Littlenut around the Lorimer stop off the L train. But when push came to shove and I was forced to confirm the most stringent detail, I had to look up Tammi Littlenut on IMDB, and alas!… Her real name is not Tammi… I mean Jamie Lowe, but Maria Thayer! Hopes dashed.

But it wasn’t a complete loss. Ms. Lowe’s highly personal detective story recounts the life, times and eventual last days of Ol’ Dirty Bastard, aka Big Baby Jesus, aka Dirt McGirt, aka, Ason Unique, aka Russell “Rusty” Jones, and is, upon further reading, an exhaustive and thorough portrait of the man himself, from growing up in Brooklyn freestyling with the RZA and developing his unorthodox and perverse rhyme scheme1 to his final days, when he was heavily medicated—both doctor prescribed and self inflicted—as he became a shell of what he once was and felt the world could probably do without him when he finally died in 2004 after a bag of cocaine he purposefully or accidentally swallowed, broke apart inside him.

Digging for Dirt includes interviews with members of the Wu Tang Clan, one of the most influential hip-hop groups of the ’90s and the ones who were closest to ODB, weird and disjointed interviews with Ol’ Dirty himself, conversations with Blowfly and doctors who related ODB’s erratic and paranoid behaviors as signs of mental illness, in his case schizophrenia. Ms. Lowe has accrued an enormous amount of material here about someone many people considered, at least in his last years, as a wash-up, a court jester gone drunk, an exploited character taken advantage of post prison and rehabilitation, and her sympathies run unapologetically deep. To Ms. Lowe, Ol’ Dirty Bastard was a childhood hero, misunderstood and unfairly judged, gorgeously outspoken and, to borrow a line from Hunter S. Thompson, “one of God’s own prototypes.” A true original.

Digging for Dirt includes interviews with members of the Wu Tang Clan, one of the most influential hip-hop groups of the ’90s and the ones who were closest to ODB, weird and disjointed interviews with Ol’ Dirty himself, conversations with Blowfly and doctors who related ODB’s erratic and paranoid behaviors as signs of mental illness, in his case schizophrenia. Ms. Lowe has accrued an enormous amount of material here about someone many people considered, at least in his last years, as a wash-up, a court jester gone drunk, an exploited character taken advantage of post prison and rehabilitation, and her sympathies run unapologetically deep. To Ms. Lowe, Ol’ Dirty Bastard was a childhood hero, misunderstood and unfairly judged, gorgeously outspoken and, to borrow a line from Hunter S. Thompson, “one of God’s own prototypes.” A true original.

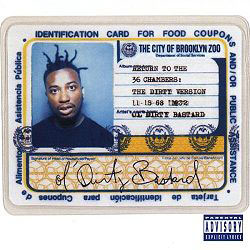

As far as I can determine, Ms. Lowe and I are about the same age. She relates how she was in tenth grade in 1992; I was in eighth grade that year, and it would be a year and a half before I first heard the Wu Tang Clan’s groundbreaking record Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers). I remember I mistakenly bought the radio-friendly record from K-Mart. In time I also had solo records by the GZA (“Liquid Swords” which I used to hear at the skatepark in Lancaster pretty frequently), Raekwon (“Only Built for Cuban Linx…” which I once read Adrian Brody name as a top five essential hip-hop record, though what authority Brody has in that scene I don’t know. It is the only surviving Wu-Tang record I still have after selling the rest for something stupid like gas money when I was in college), and Ol’ Dirty’s “Return to the 36 Chambers: The Dirty Version,” with the now famous reproduction of his welfare ID card, the photo of him with his wild braids and cockeyed eyeballs and somewhat slightly dazed expression indelibly burned into the retina of anyone who ever saw the record.

Wu-Tang was enormously popular back in those days, around 1995-96, and I used to see the RZA’s van pull into Newark, Delaware, with it’s all-over-print paint job, and (for what reason I never really found out but) kids used to go off when they saw that thing. That was the other thing that struck me about the Wu-Tang: for as much as I mixed “Protect Ya Neck” with, say, some Damnation A.D. to follow, for as groundbreaking as Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) was for an underground hip-hop group whose records were sold out of the trunk of RZA’s car, Wu-Tang stood out as the group that really broke ground with the white kids. Like Metallica and Slayer, the Wu-Tang Clan was the great equalizer—I don’t want to say they were quite a common denominator—but from the OG followers in Staten Island and Brooklyn to the suburban middle-to-lower-middle-class kids in my hometown, all had a love for the Wu-Tang. Which is where I slightly disagree with Ms. Lowe’s assertion about Wu-Tang’s appeal, “When sheltered middle-class kids played gangsta, rhyming lyrics of South Central war, it seemed ridiculous. But Wu-Tang was selling something different” (p.15).

Wu-Tang was enormously popular back in those days, around 1995-96, and I used to see the RZA’s van pull into Newark, Delaware, with it’s all-over-print paint job, and (for what reason I never really found out but) kids used to go off when they saw that thing. That was the other thing that struck me about the Wu-Tang: for as much as I mixed “Protect Ya Neck” with, say, some Damnation A.D. to follow, for as groundbreaking as Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers) was for an underground hip-hop group whose records were sold out of the trunk of RZA’s car, Wu-Tang stood out as the group that really broke ground with the white kids. Like Metallica and Slayer, the Wu-Tang Clan was the great equalizer—I don’t want to say they were quite a common denominator—but from the OG followers in Staten Island and Brooklyn to the suburban middle-to-lower-middle-class kids in my hometown, all had a love for the Wu-Tang. Which is where I slightly disagree with Ms. Lowe’s assertion about Wu-Tang’s appeal, “When sheltered middle-class kids played gangsta, rhyming lyrics of South Central war, it seemed ridiculous. But Wu-Tang was selling something different” (p.15).

I don’t disagree with the first part of Ms. Lowe’s statement. I still find it ridiculous and comical. But let me say this, as a prime example, the little brother of my best friend Sarah, had a huge Wu-Tang W sticker on the rear windshield of his white Ford Tempo. He was super scrawny, with dirty red hair, and Sarah will probably be mad at me for this, but the kid was as white as white trash could be. He would openly boast that he had “the lowest Tempo in Delaware,” chopped springs and all, to anyone who would passively listen. And yet he loved Wu-Tang and idolized them in a way that most other kids in my town and surrounding smaller towns could relate. Ol’ Dirty himself predicted as much: “Let niggas do what they wanna do. Let a nigga be free! Only people that understand this music is niggas! And the white people gonna like it anyway, ’cause white people like anything a nigga do!” (p. 96) Even Ms. Lowe attests to this: “Loving ODB had to be unconditional… It seemed like a weird requirement from a middle-class Jew who grew up on Madonna and musical theater in West LA….” Ol’ Dirty’s last performances with Insane Clown Posse and Rob “Vanilla Ice” Van Winkle speak volumes about the evolution of Wu-Tang’s audiences, but by then ODB was already long on his way out.

Admirably, Ms. Lowe makes no apologies for this. Wu-Tang is as Wu-Tang does, but one issue I did have with the text was the sporadic, almost guilty sense of keeping it real, as if no reader of Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s biography would believe the narrator as trustworthy unless a few key phrases were posthumously inserted. More than a few times I found myself marking lines like “They were all about the ‘dolla dolla bills, yo'” and other instances of contrived hip-hop vernacular with ellipses of annoyance or just plain question marks. For this I blame the editor: Ms. Lowe’s dedication to the subject and her ability to seek out and nail down the expansive array of sources she cites in the book (an interview with Blowfly at a Miami Jai-Alai court?) are enough credibility on its own without some schmuck editor telling her to make the text read “more black” (see David Foster Wallace’s essay in Consider the Lobster “Authority and American English”).

Admirably, Ms. Lowe makes no apologies for this. Wu-Tang is as Wu-Tang does, but one issue I did have with the text was the sporadic, almost guilty sense of keeping it real, as if no reader of Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s biography would believe the narrator as trustworthy unless a few key phrases were posthumously inserted. More than a few times I found myself marking lines like “They were all about the ‘dolla dolla bills, yo'” and other instances of contrived hip-hop vernacular with ellipses of annoyance or just plain question marks. For this I blame the editor: Ms. Lowe’s dedication to the subject and her ability to seek out and nail down the expansive array of sources she cites in the book (an interview with Blowfly at a Miami Jai-Alai court?) are enough credibility on its own without some schmuck editor telling her to make the text read “more black” (see David Foster Wallace’s essay in Consider the Lobster “Authority and American English”).

Ms. Lowe paints a vibrant velvet portrait of Ol’ Dirty Bastard, who died in 2004 at the age of 35 after battling with a decaying psyche and numerous affirmations that the character of Ol’ Dirty—the raucous, perverse, and chaotic persona—needed to be retired. And yet those snaggled braids and glassy eyed innocence from Return to the 36 Chambers still make clear his good heart wrenched by paranoia, fame exploitation, drug abuse, and personal demons few knew. Ms. Lowe writes a tribute to a hero as worthy as any. Kudos to her.

1 (His mother, Cherry, once told him “You have the nerve to get out there and sing when you know you can’t sing,” while Ms. Lowe’s puts it this way: “He rapped when he felt something and he deconstructed words by pouring meaning into guttural sounds. His train of thought derailed from the moment he opened his mouth.” [p142]