100% Animals: An Interview with Andrew James Weatherhead

22.09.15

Andrew James Weatherhead has been one of my favorite writers since I found out about him in 2009. He was just publishing small chapbooks and stories and poems online at that point. He was also one of the first writers I met, sometime in 2010 or 2011. I went to a reading he was giving on Atlantic Ave in Brooklyn. David Fishkind was there and he and I excitedly talked about all the writers we shared a mutual love for, mostly writers from the Internet. It was one of the first times that we had each talked with other online writers. I don’t know how to describe it. I had been reading writers like Tao Lin, Ellen Kennedy, and Noah Cicero since 2007, gathering names of related writers, such as Fishkind and Weatherhead, and their blogs. Later on, after the reading was over, I talked with Weatherhead, too. I asked what his favorite books were and I think he said, “Infinite Jest and Moby Dick.” At the end of the night I walked home from Prospect Park to Bed-Stuy, which took longer than I had expected.

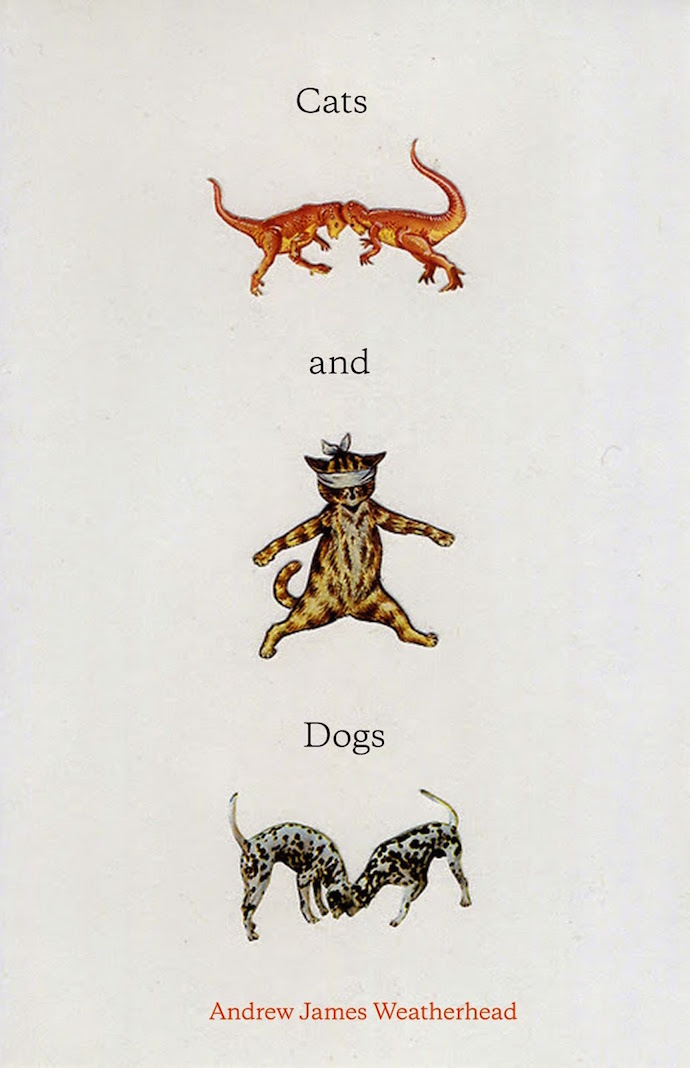

Earlier this year, Weatherhead released his first full-length book, the poetry collection Cats and Dogs, out from Scrambler Books. Our conversation below discusses the book and its genesis. – ADW

ADW: I’ve known your work for a while. Why did you decide to publish this book at this time? How did you choose which poems to include?

AJW: The book is essentially my MFA thesis, which I finished in May of 2013. That summer, which was insanely hot and terrible, I submitted it to every publisher I could think of and tried not to stress out about it. Because I had worked on the book pretty much every day for the previous year, I had no critical distance from the thing and had no idea what kind of reception it would get. I was surprised when the response wasn’t overwhelmingly negative. It was selected as a finalist in some contests, Michael Seidlinger accepted it within a few hours of me submitting it to Civil Coping Mechanisms (s/o Michael Seidlinger), and Willis Plummer wanted to release it as the first book of a publishing venture he was thinking about starting. Jeremy Spencer at Scrambler Books was one of the first people I sent it to, thinking it might fit well with their catalog, but I didn’t hear back from him until October, at which point I had already agreed to work with Willis. To make a long story short, the thing with Willis fell through, so I went back to Jeremy in February of 2014 and asked if he was still interested. Fortunately, he was. If it were up to me, the book would have come out six to eight months earlier, but I’m not complaining.

The poems date from early 2009 to summer 2014. I tried hard to balance the “I do this / I do that / look at me” style of poetry with poems whose concerns and source materials were elsewhere. I didn’t want to publish a collection that was exclusively about its author, but I wanted to be sure the book had the weight of a life behind it.

The book opens with the following quote from De Quincey: “a medical student in London, for whose knowledge in his profession I have reason to feel great respect, assured me, the other day, that a patient, in recovering from an illness, had go drunk on a beef steak.” How did you choose this epigraph?

It’s from De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, which I read during the summer of 2012. It was a no-brainer as far as epigraphs go.

How did you get the idea to start making your collages?

I don’t remember how I got the idea to start, but as soon as I made the first one I knew I had discovered something.

You studied neuroscience in college, then you went to an MFA program. Why did you decide not to follow neuroscience professionally or academically after college? Also, how do you think it fits into your writing?

It seemed like there was no opportunity for originality or self-actualization in neuroscience. Like many professions, unless you’re in the top 1% of your field, you’re probably not doing work you could call yours. I was definitely not in the top 1% of neuroscience undergraduates and I realized halfway through that I had no desire to be. I’m interested in the big questions science asks, but I have no patience for the academic politics and daily grind that being a neuroscientist in a research environment entails. As soon as I discovered contemporary literature–the fact that there were writers my age producing exciting, important work–that was all I wanted to do. I’ve learned much more about being a person by reading and writing poems than I ever would have as a neuroscientist.

In what way(s) do you think humans are animals?

I think humans are 100% animals. Thinking your status as a human makes you better or inherently different from any other living creature is crazy.

What did you like about being in an MFA program? Were there any parts you didn’t like?

I liked talking about poetry in a sincere manner with people who had different interests and backgrounds than me. I didn’t like the lack of academic or intellectual rigor. As long as you showed up you graduated, it seemed. Some people were clearly working and thinking a lot harder than others.

What were your earliest experiences with writing? When did you decide that you wanted to be serious about writing creatively?

For as long as I can remember, I’ve loved the sound of typing on a keyboard. My house was the kind of house that always had spare computer parts around and I remember carrying around a keyboard, unattached to anything, and typing on it while looking at the things I wanted to be writing about, like the TV or a tree or whatever. I remember going through a large stack of keyboards trying to find the ones that made the most satisfying typing sounds.

I started seriously writing in 2007 when I was studying abroad in Paris and took a creative writing class by accident.

Where do you live? Do you like where you live?

I live in Brooklyn. I like it, though I constantly entertain the idea of moving home to Chicago.

I think of you as a writer I know from the internet. What kind of role has the internet had for you and on your writing?

The internet has been immensely important. Discovering writers around my same age who were actively writing and publishing was very inspiring. It seems silly in retrospect, but prior to discovering writers on the internet, I thought that becoming a writer was something you did in your thirties or forties, a decidedly middle-age pursuit. Finding other “young people” interested in writing via the internet was huge. Cats and Dogs would never have been written without the internet.

If you were dying in 60 or 70 years, and your memory wasn’t as strong, what would be one memory about contemporary literature that you would still have? Is there anything distinct? Does anything exciting happen in “the literary world”?

Megan Boyle’s liveblog was pretty incredible.

Who were you reading a lot when you were writing the poems in this collection? Would you say there are any direct influences on your style/book?

There were so many. The poems span five years of writing, so there were numerous phases and interests that got incorporated into the final collection. I could probably go through the book, poem by poem, and tell you what I was influenced or inspired by at that time:

“Something that Happened in Brooklyn” was inspired by a poem from my first MFA workshop.

“Brisk October Poem” was inspired by Matthew Zapruder’s book Come On All You Ghosts.

“St. Patrick’s Day” was inspired by Facebook.com.

“The Truth” was influenced by Wallace Stevens probably.

“Poem” was influenced by the poetry of Jerimee Bloemeke, and his publishing collective, HUMAN 500, which also includes the poets Henry Finch and Jeff Griffin.

“Document #5” and “The Bag Plopped into the Middle” were inspired by the poetry of Michael Earl Craig.

“Haiku in the Modern Manner” and “Haiku in the Traditional Manner” felt inspired by the poetry of Ben Fama somehow.

“Non-Fictions” was inspired by a student reading I went to at The New School.

“Playing Tennis Against a Wall” was influenced by the poetry of James Schuyler.

“Love Poem” was influenced by the poetry of Graham Foust.

“Friday” and “America” were inspired by my reading of the Objectivist poets, primarily George Oppen and Lorine Niedecker.

“A Private View of Butt City” was influenced by Ben Mirov’s chapbook I is to Vorticism.

“Thank You Notes” was inspired by things I found in an old desk in my parents’ house (see next question).

“Haiku after Ishiguro” was inspired by Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel Remains of the Day.

“Poem” was influenced by Megan Boyle’s twitter account, I think.

“Poems for the Morning Commute” was inspired by my reading of the Objectivist poets, primarily George Oppen and Lorine Niedecker.

“3:21 am” was inspired by my reading of the Objectivist poets, primarily George Oppen and Lorine Niedecker.

“CVS” was inspired by my reading of the Objectivist poets, primarily George Oppen and Lorine Niedecker.

“The Cat Gets Bold” was inspired by my reading of the Objectivist poets, primarily George Oppen and Lorine Niedecker.

“New Pants” was influenced by the poetry of John Ashbery.

“Poem on the R Train” was inspired by my reading of the Objectivist poets, primarily George Oppen and Lorine Niedecker.

“End of Summer” was influenced by an anthology of Chinese Zen poetry called A Drifting Boat: Chinese Zen Poetry.

“Poem Above Clouds” was inspired by a Georgia O’Keefe painting called “Sky Above Clouds IV.”

“Take it Easy” was influenced by Matthew Rohrer’s book Destroyer and Preserver.

“sitting in the yard, everything is a distraction” was influenced by the poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley, whose name I misspell in the poem, embarrassingly.

“Selling Drugs” was inspired by the poetry of Graham Foust.

“Poem for my neighbor’s bird, which I took care of for 10 days while they were in Turkey” was inspired by Jon Woodward.

“A Letter” was influenced by my reading of the Romantic poets, primarily Shelley and Keats.

“House Fire” was inspired by Wallace Stevens.

“Hell Has Gradations” was inspired by Max Jacob’s poem of the same name.

“9/9/11” was inspired by something I heard on NPR and Matthew Rohrer’s book Destroyer and Preserver.

“Washington, George” was found in the index of David McCullough’s book 1776.

“Me, You, and Everyone We Knew” was influenced by my reading of the Romantic poets, primarily Shelley and Keats.

“What Happens When Your Dad Dies” was influenced by Sarah Jean Alexander’s writing maybe.

To summarize, the Objectivist poets–primarily George Oppen and Lorine Niedecker–left a huge imprint on this book, Matthew Rohrer’s poetry has always been a guiding light, and Wallace Stevens is my favorite poet.

What was the process of writing the poem “Thank You Notes,” which is framed as a letter from the Department of Education?

I was at my childhood house in Wilmette, Illinois. I was sitting at an old desk, which had once belonged to my grandfather. I started rummaging through it and found a stack of unused thank you notes. I started writing on the thank you notes using other things I found in the desk as inspiration. I remember there was a Pete Rose baseball card, a map or diagram of some sort, and a letter from the Department of Education. This all happened very late at night, maybe 1 or 2 AM, and I remember the wind was blowing.

How was it working with Jeremy Spencer, who runs your publisher, Scrambler Books?

He was incredible. He nailed the book design. I think my only input was that I wanted off-white paper and, from that, he created exactly the book I had imagined in my head. The covers, the font, the spacing — I couldn’t have asked for a better looking book. Highly recommend working with him. He’s also an avid NBA fan, so that’s a bonus.

What are some types of poetry or writing that you don’t like? Why don’t you like them?

I don’t think there’s any type of poetry or writing I don’t like. I don’t understand it when people say they don’t like a particular genre or style or medium, whether in literature or elsewhere. For example, you frequently hear people say they don’t like country music. That makes no sense. There’s an enormous, insane variety of music that could be described as “country music”–how could you possibly dismiss all of it in one fell swoop? You hear people make the same sort of sweeping judgements about conceptual literature, street art, landscape photography, ballet, musical theater, romantic comedies, deconstructivist architecture, etc. etc. These are broad, unconditional judgements based on generalizations made by people who usually have limited experience with the thing they’re judging. To me, this kind of narrow-minded thinking is not far removed from the stereotyping that leads to racism, sexism, xenophobia, and homophobia.

What is culture if not an expression of identity? To categorically dismiss any of it based on superficial characteristics feels wrong.

Of course there are writers and artists I don’t care for, I just think it’s extremely important to consider them as individuals, not as representatives of anything more than themselves. For example, I don’t like John Updike.

The poems in this book refer to brands like “Cheetos,” “CVS,” “The Simpsons,” and “Golden State Warriors.” But the way you present these words doesn’t make it seem like they are products to be bought and sold, as in fact they are. Money isn’t really at stake. Do you think about how these are brands/products when you introduce them into your work? Are these just everyday, important parts of our lives, that can’t be avoided in poetry like they might have 100 years ago?

They could definitely be avoided in poetry, but why? If the concern is dating my poems, somehow restricting their cultural longevity by introducing contemporary proper nouns, I’d counter with the fact that each of the brands you list is pretty much guaranteed to have far greater cultural longevity than any of my poems. If cultural longevity is the concern, then the real question is why am I writing poems instead of trying to become a Cheetos executive or an assistant coach for the Warriors?

If you had to choose to do an activity related to one of the following, Basketball or Poetry, for the rest of your life, which would you choose? Why?

Right now I’d say Poetry, but there have definitely been times when I’d choose Basketball. I’m not sure I have a good answer for why. They’re both awesome.

The last line of one of this book’s poems says, “In 2012, 141 people / were killed by trains.” This is the end of a short poem reflecting on how we don’t even know how much we know. I feel like this fact you put at the end is something that was on the MTA subway advertisements at some point. Was it? Could you think of other examples of things that you could put at the end of this poem?

Yes, that was from an MTA poster. I don’t think anything could replace those lines in that poem.

Where do you see yourself and your writing 10 years from now?

I want to write more fiction. I have a book coming out next year with Monster House Press–tentatively called Aardvark–which will be poetry, but different from Cats and Dogs. There are two novels I’m working on that I’d like to finish in the next 10 years.