World and War Memories: A Review of Don Mee Choi’s Hardly War

29.09.16

Hardly War

Hardly War

by Don Mee Choi

Wave Books

112 pp / $18.00

It’s partly a book of a father’s photographs, partly a book of a daughter’s poems. There’s plenty of memories and contexts circulating (like secret antiwar newspapers), but the American illogic takes its toll. There’s x amount of equations, but with chemistry comes disturbing consequences (“65% oleic acid + 30% coconut fatty acid + 5% naphthenic acid”). It’s not the ingredients, but how they mix. And who is supplying them. It’s hardly war. It’s the way evidence goes missing. The way some bodies count. And why others do not. The way a reader’s mouth can’t form a phrase like “world memories” without first forming a “war” sound. Worrrrrld. Warrrrrr. The way a machine’s “almost human understanding” reminds you of what makes so many machines, in fact, killing machines. Like an entrancing, explosive flash from a haunted camera, Don Mee Choi’s Hardly War vividly preserves the flesh and ghosts of wartime Korea and Vietnam.

Hardly War isn’t just a book, but a film-like book or a book-like opera. If one were to perform Hardly War as a live opera, I wonder what it might look like. How would its untranslated and untranslatable parts translate to a stage? I feel it would be necessary to project the book’s photographs against a backdrop. Especially in regard to rendering Barthes’ concept of punctum in photography, something he describes in Camera Lucida as “what I add to the photograph and what is nonetheless already there.” On page 33 of Hardly War, there’s a moment of text that reads, “AGAIN A / PERFECT / BULL’S-EYE.” Having already been cued by the Barthes quote that opens the book,

The Photograph then becomes a bizarre medium, a new form of hallucination: false on the level of perception, true on the level of time: a temporal hallucination, so to speak, a modest, shared hallucination (on the one hand ‘it is not there,’ on the other ‘but it has indeed been’): a mad image, chafed by reality.

I attempt to read the photograph. I bull’s-eye my way across the photograph. I try to locate the punctum. I dwell on this medium—the medium of photography as well as the medium who is linked and speaking to a world of spirits. The means and the end. I look for whatever wounds my eye. What wounds my eye? I see a soldier’s helmet. Is this the punctum? I see a rectangular object that a woman on the back of a motorcycle is holding against her face. What is that object? Is she using that object to shield her face from the wind on a motorcycle in motion? Or, is she concealing her face because she doesn’t want to be recognized?

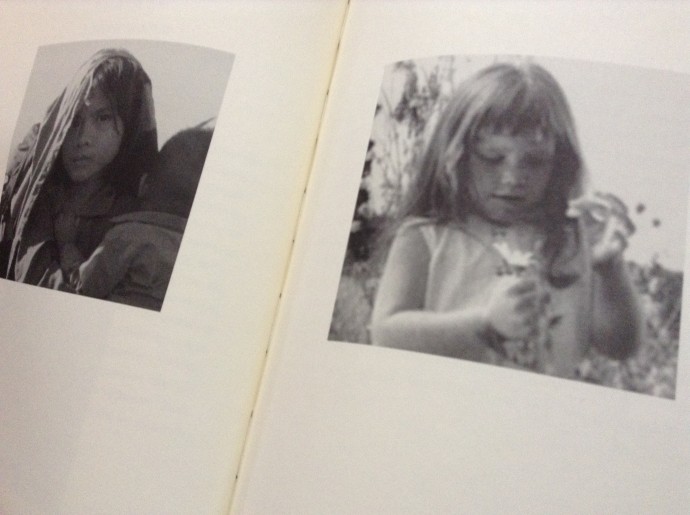

I turn the page. Another photograph. I try to locate the punctum: a baby’s hand clutching the collar of a little girl. Why is this baby a little girl’s responsibility? I see a different little girl on the following page. The second little girl isn’t wearing a cloak like the first. I return to the photograph featuring the cloaked girl and the baby. Maybe the baby’s hand isn’t the punctum. Perhaps it is the cloak the little girl is wearing. Why is the little girl in the first photograph wearing a cloak, but the little girl in the second photograph isn’t? I bull’s-eye back and forth from page to page. These are two very different little girls. I try to locate the punctum: is it the daisy in the little girl’s right hand, or the petal she’s plucked with the fingers of her left hand? What is she counting? Is she playing a game? Why is only one of them seem capable of forming a smile?

I turn the page and leave the photographs behind. Some lines in a poem titled, “I, Lack-a-Daisy” read:

I, Lack-a-daisy, born two miles from every place, every suspect, every petal kicked open, am deeply moved by world memories. There is no choice in the matter. What are world memories? It turns out they are war memories. And what are war memories? They are orphan memories.

Then I read the next poem titled, “Daisy Serenade” and I linger over,

5 Or o?=Do you know?=0 or 5?=Do you know?=Yi Sang knows

7 I style stigma=style anther=then sepal ovule=Over

6 I sang=I sang=like a daisy

6 I fugue=I fugue=like a daisy

At times I feel as though I am trying to translate a punctum language. It feels as though I am reading poems in which punctum and studium are lodged in conversation, in maddening conflict. I suddenly realize these poems are already altering the ways in which I’ll re-read the photographs later. The “ = ” reminds me of an eye searching for punctum. But what to make of the counting up and down of the numbers in relation to the equation-like poems? Yi-Sang’s presence in “Daisy Serenade” makes me wonder if I should be approaching these poems as existential puzzles:

0 We must love one another or die

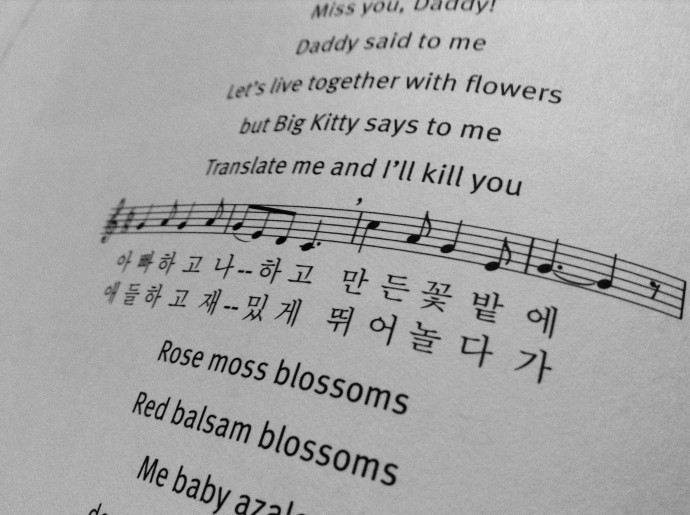

At this point I find myself thinking it might not even be entirely possible to review this book. Perhaps I have already put too much of myself into this review. (Perhaps that’s what Don Mee Choi wanted.) The book feels more and more like a piece of codified music one has to experience for themselves. But I’m not sure I can entirely experience the music without knowing how to read the code. Without translating. Suddenly the book—a poem called “Daddy’s Flower Bed” offers a line of music, but something called Big Kitty appears and threatens both the speaker and the reader of the poem:

In the deathly, blueprint-like section titled, “Purely Illustrative,” Choi draws a connection between the postcard image of the USS Kitty Hawk (CV-63), a United States warship and Hello Kitty, a cute, anthropomorphic Japanese cat character. (An icon worth billions of dollars—you name the consumer product, and Hello Kitty has appeared on it.) In Our Aesthetic Categories, Sianne Ngai suggests an often-overlooked relationship between cuteness and female powerlessness. She writes, “The more objectified the object, or the more visibly shaped by the affective demands and/or projections of the subject, the cuter.” Choi sometimes employs an aesthetisized, cutified language that resists brainwashy, wartime-imposed constrictions and emphasizes her geopolitical poeisis. I read the often alliterative examples as a reverse of the violence done to bodies made powerless. The language—cheerily cherrily; merely merrily; counter-counterly; narrowly narrower; spraying sparingly—is hardly “cute” given the context of the book. The language reads more like some sort of sinister cuteness. This language of innuendo and even pun (“Woe are you?”) demonstrates how cutification can be integrated into poetry to make something seemingly innocent or innocuous feel absolutely threatening.

Choi pushes the language of sinister cutification even further on page 42 when she introduces a Hello Kitty-like “anti-CHORUS” that sings a song of exclamations in response to the black crew members who, while aboard the USS Kitty Hawk, staged a protest against the war in 1972. The first kitten sings “I, aye-aye-sir!” and another sings, “I, kitty-litter-sir!” At first, these singing kittens in “frilly white bonnets” sound like unthreatening, obedient little kittens. However, Choi provides a highly informative glossary in the book that reveals “kitty litter” to be the same name as the antiwar newspaper that circulated aboard the USS Kitty Hawk. Of course, the American news media labeled the incident a “race riot” as opposed to acknowledging it for what it was: an antiwar protest.

Hardly War concludes with “Hardly Opera,” a section of the book that I personally think is best read aloud:

I-like-a I-like-a

I take a look I-like-a

A copy of LIFE magazine

O-Pinkville O-like-Me

As far as war is involved such a thing is happening

Anywhere any place any nation

I-like-a

The poems within “Hardly Opera” swell outward from the center. Bomb-like, they expel a shrapnel that flowers in the form of seaweed and azaleas and cherry blossoms. In fact, the azaleas and the cherry blossoms sing: “Army / Navy / Air Force / Marine commanders / Rosy-posy! / They posed in front of the map / not an ordinary map / wires / flags / hills / mines / pajamas.” It’s the kind of song that reminds me of a bomb. It’s the kind of song that reminds me of a daisy cutter.

It seems like nothing in Hardly War is what it appears to be on the surface. Again, much of it feels like some sort of punctum language in which we must read and then re-read if we want to make sense of things. If Americans want to de-camouflage their long, long history of violence. From discovering the vile ways in which the U.S. military utilized Smokey the Bear as propaganda during the 1960s to the relationship between the song “White Christmas” and Saigon evacuations, there were times when I literally had to set this book down to reflect on what it means to be an “American”—then and now. It is not a book you will finish in a single sitting. This stunning book—this arrangement of recurring hydrangeas and chemical materials; of artillery rounds and detonating mechanisms; of rebellions against incendiary government-sponsored thinking—is a must-read. A truly difficult read, but a must! Why? The truth can be a frightening, gut-wrenching thing. Do you think you can ignore it?

Hardly.