!Women Art Revolution! – Lynn Hershman Leeson

07.08.11

It could be said that Lynn Hershman Leeson does not make good movies. Good, in a sense that is respective to the populist prerogative of feature-length and therefore commercially viable, movies. Films of a certain economic tenacity, seamless pictures that we submit to systems of evaluation that, even to those products that presently receive 3, 4, or 5 star appraisals, seem anachronistic or moot. Though Leeson currently moves in this world, it is only a matter of pragmatism. As in her career as a visual artist, the goals of Leeson’s feature career are antithetical to those purportedly empirical in the project that is dominant filmmaking. Her feature-length efforts do not place the same emphasis on plot or narrative unfolding as most Hollywood cinema or feted docs; nor do they, ultimately, convene with a customary sense of finitude. No, Leeson came from an early 70s art world teased by the promises of a) advanced technology and b) the burgeoning feminist art movement. Leeson took both strains to task for over 40 years, making cyber mock-ups for female robots, taking avatars at face value and allowing one, Roberta Breitmore, to overtake her everyday life, by problematizing the private via female-coded lexical diatribes, like a teenage weblog, in searing and hilarious video diaries. Her next step––the pictures!––happily did little to upset this content. In her feature films, Leeson allows the techno-political content to trump form, forging a body of work strikingly original and defiantly rich.

It could be said that Lynn Hershman Leeson does not make good movies. Good, in a sense that is respective to the populist prerogative of feature-length and therefore commercially viable, movies. Films of a certain economic tenacity, seamless pictures that we submit to systems of evaluation that, even to those products that presently receive 3, 4, or 5 star appraisals, seem anachronistic or moot. Though Leeson currently moves in this world, it is only a matter of pragmatism. As in her career as a visual artist, the goals of Leeson’s feature career are antithetical to those purportedly empirical in the project that is dominant filmmaking. Her feature-length efforts do not place the same emphasis on plot or narrative unfolding as most Hollywood cinema or feted docs; nor do they, ultimately, convene with a customary sense of finitude. No, Leeson came from an early 70s art world teased by the promises of a) advanced technology and b) the burgeoning feminist art movement. Leeson took both strains to task for over 40 years, making cyber mock-ups for female robots, taking avatars at face value and allowing one, Roberta Breitmore, to overtake her everyday life, by problematizing the private via female-coded lexical diatribes, like a teenage weblog, in searing and hilarious video diaries. Her next step––the pictures!––happily did little to upset this content. In her feature films, Leeson allows the techno-political content to trump form, forging a body of work strikingly original and defiantly rich.

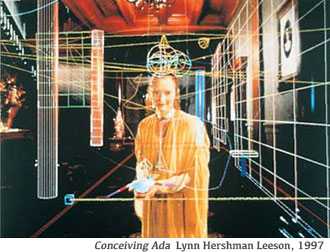

Her feature-length "film" career began in 1997 by way of her artistic collaboration with actress Tilda Swinton. Conceiving Ada is about a contemporary woman who invents a program that allows her to reach into the past to contact Ada Lovelace, the first figure on record to hypothesize a computer language. Conceiving Ada looks cheap; it can be a rather plodding watch. But there’s a suavity there, in its technoswagger, a geek chic that tears at its three-act format. Like the avatar/Tilda that stares out through the program/portal, there’s a sense that the film’s intelligent bravado spills beyond the parameters of this silly, prescriptive structure––a mere requisite for distribution. This is a pliable platform for ideas and information, Leeson knows instinctively, rather than an invisible theater that is (was?) storytelling. Teknolust (2002) followed with an appealing premise: a Feminist revision of the Frankenstein tale, as it befits the human genome. Which, in no small pleasure, makes for four Tildas in one film. They dance, they smirk, they take in the classics on projectors as they sleep. And they learn from them. Teknolust is a much more robust film. It’s got a narrative, a pull. Each of the three clones that Dr. Rosetta Stone produces from her DNA, bear a color and name RGB’s hues. In a manner similar to her feminist peers, Leeson’s gesture, the aesthetic classification or coding of her characters, feels at once trite, and yet somehow subversive by way of its heavy-handed application; it’s a camp hoodwink that explodes such reductionism. The analogy between molecular and additive color models is messy, but the ideas are fertile for analysis. The film is still notably low-budget, but the gumption of its actors and its intellectual self-assurance send it into a realm beyond the late night nudie that distributors thought would boost DVD sales. The Hollywood model is irreconcilable with this thinking woman’s cinema; if their lavish means escape Leeson, it allows her content to take center stage, exhibiting an idea-based cinema.

Her feature-length "film" career began in 1997 by way of her artistic collaboration with actress Tilda Swinton. Conceiving Ada is about a contemporary woman who invents a program that allows her to reach into the past to contact Ada Lovelace, the first figure on record to hypothesize a computer language. Conceiving Ada looks cheap; it can be a rather plodding watch. But there’s a suavity there, in its technoswagger, a geek chic that tears at its three-act format. Like the avatar/Tilda that stares out through the program/portal, there’s a sense that the film’s intelligent bravado spills beyond the parameters of this silly, prescriptive structure––a mere requisite for distribution. This is a pliable platform for ideas and information, Leeson knows instinctively, rather than an invisible theater that is (was?) storytelling. Teknolust (2002) followed with an appealing premise: a Feminist revision of the Frankenstein tale, as it befits the human genome. Which, in no small pleasure, makes for four Tildas in one film. They dance, they smirk, they take in the classics on projectors as they sleep. And they learn from them. Teknolust is a much more robust film. It’s got a narrative, a pull. Each of the three clones that Dr. Rosetta Stone produces from her DNA, bear a color and name RGB’s hues. In a manner similar to her feminist peers, Leeson’s gesture, the aesthetic classification or coding of her characters, feels at once trite, and yet somehow subversive by way of its heavy-handed application; it’s a camp hoodwink that explodes such reductionism. The analogy between molecular and additive color models is messy, but the ideas are fertile for analysis. The film is still notably low-budget, but the gumption of its actors and its intellectual self-assurance send it into a realm beyond the late night nudie that distributors thought would boost DVD sales. The Hollywood model is irreconcilable with this thinking woman’s cinema; if their lavish means escape Leeson, it allows her content to take center stage, exhibiting an idea-based cinema.

Strange Culture (2007) was an important step for Leeson (who continues to produce visual art in what is now a truly prolific career). This film sumptuously blends documentary and fiction film form. Telling the story of Steve Kurtz, a research-based artist arrested for his incorporation of biological elements and analysis in his artwork, Leeson again employed Swinton to play Kurtz’s wife (whose death was the catalyst for his arrest) and Thomas Jay Ryan to play Kurtz. In documentary form, Kurtz shares screentime with his fictional surrogate, as talking head. Further, Leeson engages her collaborators––which is to say, her actor––in a discussion of the case, between takes, as the camera rolls on. Fictions and representations fold in upon themselves and narratives start and stutter. The case remains open ended at the close of the film, offering no resolution, so that the issues dredged up tend to explode beyond the case’s particulars. It’s a bewildering piece, a remarkable confrontation between filmworld and artworld, where a ubiquitous new piece in art news, stirred only nominal interest in a moviegoing public.

Strange Culture (2007) was an important step for Leeson (who continues to produce visual art in what is now a truly prolific career). This film sumptuously blends documentary and fiction film form. Telling the story of Steve Kurtz, a research-based artist arrested for his incorporation of biological elements and analysis in his artwork, Leeson again employed Swinton to play Kurtz’s wife (whose death was the catalyst for his arrest) and Thomas Jay Ryan to play Kurtz. In documentary form, Kurtz shares screentime with his fictional surrogate, as talking head. Further, Leeson engages her collaborators––which is to say, her actor––in a discussion of the case, between takes, as the camera rolls on. Fictions and representations fold in upon themselves and narratives start and stutter. The case remains open ended at the close of the film, offering no resolution, so that the issues dredged up tend to explode beyond the case’s particulars. It’s a bewildering piece, a remarkable confrontation between filmworld and artworld, where a ubiquitous new piece in art news, stirred only nominal interest in a moviegoing public.

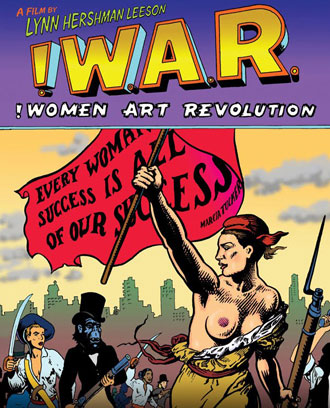

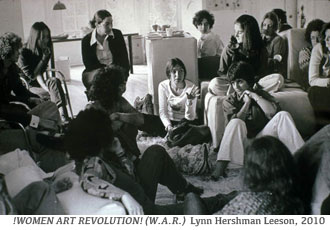

Now, !Women Art Revolution! storms theaters across the US. It’s an important revisionist vie for historiography, a smart and sober demand for reparation. WAR (as it is also called) is all the more nimble since its maker was involved in the (invisible) herstory that the film works to set straight. As in her video diaries, Leeson confesses her conceptual dilemma early on: whether she ought to include herself in this film, as both an artist and historiographer. Would this seem too self-serving? But then, revealing the true wit at the heart of her early time-based projects, she declines to abide by a self-omission and censorship that has, historically, made a film such as this necessary in the first place. Her personal devastations become leitmotifs in the larger lineage.

For WAR, Leeson collected video portraits over the years, interviewing key figures about their uphill struggle for art world recognition. Heavy-hitters testify, like Judy Chicago, Hannah Wilke, Yvonne Rainer, Eleanor Antin, Janine Antoni, Martha Rosler, Miriam Schapiro, Carolee Schneeman, Connie Butler, Nancy Spero and, of course, the Gorilla Girls. And Leeson presents first-hand documentation of famous artworks and events like the opening party for the Dinner Table; the opening of A.I.R. Gallery and the death of Ana Mendieta; the opening and closing of Calart’s feminism program and its resulting installation, Womanhouse; and the opening of the WACK! Exhibition at MOCA, Los Angeles. The film is rousing in its claims (I must confess to a couple emotional moments) and informative for its inclusion of those figures who still linger outside the dominant timeline of The Feminist hagiography. As founding groups disperse, there’s a mild lag once the film shifts to focus on the Gorilla Girls, whose presence, here, struck me less with their signature curt immediacy and more for a kind of vaudevillian metastasis. But narrative flow is obviously not the stake of WAR. As with Leeson’s previous efforts, formal faults are many, but aesthetic foibles account to little in the scope of this project. Which does little to excuse the wrap-up, however, which projects a surprisingly rosy air of progress. The opening of one touring exhibition (WACK) does not, in itself, indicate a significant change in ways. I can attest. On a recent studio visit with a female artist, we found ourselves flipping through a current issue of Artforum as an exercise, to count the galleries with more than the token woman artist among their roster. Our lark yielded no laughs.

For WAR, Leeson collected video portraits over the years, interviewing key figures about their uphill struggle for art world recognition. Heavy-hitters testify, like Judy Chicago, Hannah Wilke, Yvonne Rainer, Eleanor Antin, Janine Antoni, Martha Rosler, Miriam Schapiro, Carolee Schneeman, Connie Butler, Nancy Spero and, of course, the Gorilla Girls. And Leeson presents first-hand documentation of famous artworks and events like the opening party for the Dinner Table; the opening of A.I.R. Gallery and the death of Ana Mendieta; the opening and closing of Calart’s feminism program and its resulting installation, Womanhouse; and the opening of the WACK! Exhibition at MOCA, Los Angeles. The film is rousing in its claims (I must confess to a couple emotional moments) and informative for its inclusion of those figures who still linger outside the dominant timeline of The Feminist hagiography. As founding groups disperse, there’s a mild lag once the film shifts to focus on the Gorilla Girls, whose presence, here, struck me less with their signature curt immediacy and more for a kind of vaudevillian metastasis. But narrative flow is obviously not the stake of WAR. As with Leeson’s previous efforts, formal faults are many, but aesthetic foibles account to little in the scope of this project. Which does little to excuse the wrap-up, however, which projects a surprisingly rosy air of progress. The opening of one touring exhibition (WACK) does not, in itself, indicate a significant change in ways. I can attest. On a recent studio visit with a female artist, we found ourselves flipping through a current issue of Artforum as an exercise, to count the galleries with more than the token woman artist among their roster. Our lark yielded no laughs.

A smarter addendum (knowingly proceeding Wack!’s opening) is WAR‘s waning moments where Leeson lists the thousands of hours of footage collected for this 80 minute doc, stories cut from this summation of a "secret history." Those excised histories, she narrates, are available to all on WAR‘s sister website, RAW, a feminist community where all of the material is readily accessible. What’s more, RAW is in the process of compiling an archive "built on user contributions, with the goal of creating a history defined by the community." For isn’t it really an anachronistic experience, to watch this herstory, to watch any history, in the movie theaters these days? Time, let alone a collective experience, is pervasive. To reduce it through a prescriptive editing process that rends a lifetime to bullet points would be a great discredit, particularly when the story at hand is one that hums with the scorn of exclusion. Leeson, ever savvy at contemporary media and its discontents, has done her part to turn against dominant cinema’s reductive narratologies, designing a community archive that exponentially builds on this temporal experience. She’s done more than her part to bring the hushed proponents of this history to the fore, hopefully paving the way for future generations. Placing the onus on us.

A smarter addendum (knowingly proceeding Wack!’s opening) is WAR‘s waning moments where Leeson lists the thousands of hours of footage collected for this 80 minute doc, stories cut from this summation of a "secret history." Those excised histories, she narrates, are available to all on WAR‘s sister website, RAW, a feminist community where all of the material is readily accessible. What’s more, RAW is in the process of compiling an archive "built on user contributions, with the goal of creating a history defined by the community." For isn’t it really an anachronistic experience, to watch this herstory, to watch any history, in the movie theaters these days? Time, let alone a collective experience, is pervasive. To reduce it through a prescriptive editing process that rends a lifetime to bullet points would be a great discredit, particularly when the story at hand is one that hums with the scorn of exclusion. Leeson, ever savvy at contemporary media and its discontents, has done her part to turn against dominant cinema’s reductive narratologies, designing a community archive that exponentially builds on this temporal experience. She’s done more than her part to bring the hushed proponents of this history to the fore, hopefully paving the way for future generations. Placing the onus on us.