WHITE OUT: An Interview with Michael W. Clune

30.06.15

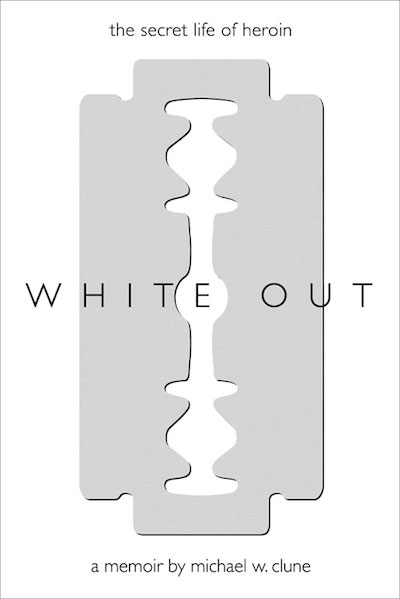

I read Michael W. Clune’s book, White Out, over Christmas, which felt like an appropriate time. It is an extended memoir or personal essay or collection of essays, dealing with his once long-running bout with heroin addiction. Before reading, I thought maybe this was just some college professor trying to write a creative manuscript after several successes with academic literature, the kind that I encountered from some of my own professors in graduate school.

I couldn’t have been more wrong. Instead, I was reading a story that was instantly recognizable as among the best of drug literature, from Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater to William S. Burroughs’s Junky to Bret Easton Ellis’s early novels. It felt like the contemporary answer to those classics.

It also was hard for me not to feel like I was on the peripheral of the TV show, The Wire. With the bulk of the narrative taking place in Baltimore while Clune was a graduate student and instructor there in the 1990s–although also set in northern Ohio, suburban Chicago, and lower Manhattan–the memoir deals with the distances a man will go to get high.

There aren’t any university graduate students on The Wire, aside from one gang boss who is a business student, and even then it is implied that he is an undergrad. It was intriguing to see this less violent but still very chaotic side of the drug world and the people experiencing it, through memories told with a sort of disturbing, visceral clarity. As Clune puts it in the interview below, this can be considered a “memory disease.”

And oh yeah, this disease is communicated through some of the most precise and beautiful prose I’ve ever read.

What made you want to write when were you were first writing creatively?

What made you want to write when were you were first writing creatively?

I was complaining to my girlfriend about all the crappy addiction books, and she said, “Why don’t you shut up and write your own then?” So I started, and it came pretty fast and clear. My “voice,” as I guess creative writing people call it, though I don’t speak like I write. Before the creative prose, I’d written a lot of bad poetry. I don’t talk about that.

Do you like writing creatively or academically more, or do you not see the distinction to be all that clear?

Certain problems lend themselves to creative writing, and others to academic methods. Sometimes the genres work together. For example, after I wrote White Out, I began to investigate some of the ideas raised allusively there in a more systematic way. One piece came out in a neuroscience journal called Behavioral and Brain Sciences in 2008, and the rest evolved into Writing Against Time, an academic book published in 2013, a few months before White Out. I think of them as companion volumes, two different ways of processing the same basic insight about the nature of human time.

Describe the moment when you knew White Out was done. How long did it take to write?

My memory of finishing White Out has been usurped by the nightmarish memories of trying to get it published. The market was flooded with addiction memoirs, and editors kept trying to get me to turn it into a kind of hybrid book where I’d weave my own experience into a history of drug use in the US or something. I actually spent a couple months trying to do this, and then my partner at the time read it and said it made her want to barf so I stopped. Hazelden was the only publisher willing to do the book as I’d originally written it. They mostly do self-help books, and one of the funny things about White Out’s reception is that the self-help crowd seems largely to hate the book (some great negative reviews on Amazon illustrate this). Anyway, when Hazelden said they’d publish it, I finally realized that I was done writing the book, even though this was years after I’d actually finished it. It was mostly written in 2006 and 2007, though some bits got added later.

Were there any models you used as inspiration?

Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium Eater is the best book on drugs ever written, and it definitely influenced me. Two other writers, both French, had a big influence on White Out. Celine’s brand of dark comedy struck me as a revelation when I first read it in 2004 or 2005. And Proust is simply the best writer and thinker about memory; a lot of my writing about addiction as a memory disease develops in a Proustian key—intellectually if not stylistically. I first read Proust when I was seventeen, and it colonized my brain. I began writing a diary in a kind of Proustian style, but somehow my life and his style switched places. I believe this was responsible for the nervous breakdown I suffered later that year. That’s not a joke. Now I stay away from Proustian style. His thinking though, no way to stay away from that.

Did you find it difficult to write so vividly about your drug experiences, even though you have been sober for a while now?

I’ve been clean for thirteen years and my drug experiences are more vivid to me than anything that’s happened in the last week. That’s addiction. It’s a memory disease. It’s very easy to access those memories at any time. I usually don’t. In normal life, it can be dangerous. Touching the image of heroin through the writing, though, that was beautiful. For me, when I’m writing, everything looks beautiful. Whether the memory is harrowing or horrible or hilarious or ugly or violent. When I’m writing, it all looks beautiful.

Do you believe the American psyche and culture make it more of a breeding ground for addiction? For example, we love movies about violence and drugs and we also have a prevalence of violence and drugs. Or it is mutual relationship?

I don’t think movies or books or games about violence and drugs necessarily increase addiction. But I do think there are thousands of addictive threads hanging down into all of our lives, and a stray movement might brush one and doom you. Not to sound paranoid. Email, for example. The expectation that there will be a new email in my inbox can keep me clicking hundreds of times a day. That base desire for novelty, for something new, is the kernel of addiction. That’s why some researchers think gambling is the ur-form of addiction. Mindlessly pulling the slot in mindless expectation of something new and good. That’s why I’m not on social media.

How do hip hop lyrics, including gangster rap, fit into turn-of-the-century trends in American poetics?

One of the things that rap lyrics do is to interpret money. This is a basic and amazing function. I remember when Biggie rapped that he likes money “because it got that whip appeal.” Why is money good? Money is good because you can buy cars with it. Most people don’t ever ask why money is good, but rap asks all the time, and comes up with some interesting and persuasive answers. I’ve written a bit about how for some gangster rap, money is good because it makes you invisible. So it’s wrong to say America is a society ruled by money. In America we have an art form that interprets money for us. I find this to be hopeful.

Who are your favorite rappers or artists currently? Why do you like them?

My favorite rapper right now is Lil Durk. A lot of the Chicago rappers are taking that sing-songy flow New Orleans rappers like Turk were doing back in 1999, 2000, and pushing it to the next level. I think maybe it’s originally a Midwest thing—think Bone Thugs in the mid-nineties in Cleveland. There’s something about dark lyrics and bright melody that gets into the part of my brain where the motivational centers are. When I need to get motivated, I listen to sing-songy raps about killing people for money. It’s not about the violence. Dark lyrics mixed with bright melody produces motivation. At least for me. For my friend Dave, too. Maybe there’s more of us. Blue and yellow makes green. And then there’s Young Thug. I remember when I first heard Young Thug, it was early 2013, I think. I thought, if this guy can actually become a star then China better watch out. America is getting stronger. And now he’s a star.

Do you like living in Northeast Ohio?

Yes, I live in Shaker Heights and I really like it. The Cleveland Orchestra’s series of Bruckner concerts in 2011 changed my life, for that alone I’d be grateful that I live here.

Do you think anything makes it distinct? Does anything make the Midwest distinct?

I think it might be a little easier to create your own zone here. Plus the constant winter/summer shift keeps your mood in tatters, which is good for art. But the main thing that makes it distinct is that it’s the easiest part of the country to drive in. The traffic isn’t as bad as the coasts, and the public transportation usually sucks, so there’s no excuse not to drive, and driving is basically my favorite thing to do.

What writing are your working on now?

I’m going through the proofs for my next book, Gamelife, which will be out from Farrar, Straus, and Giroux in September. The book looks at seven years of my early life through the lens of seven early computer games. I’d always wanted a way to talk about the part of growing up that doesn’t involve other people, and the games gave me a way. My other current project is an academic essay called, “How Poems Know What It’s Like to Die.”

Do you like academia? Do you like teaching?

I teach two classes each semester, and I try to make my classes little labs where we try to discover something new, little spaces where new thoughts appear. It doesn’t always work, but it works often enough to be one of my favorite activities. I’ve got a sabbatical due but I’ve been putting it off. I like teaching. Academia is a wonderful thing, but it’s under attack. Mainly because of the Republican defunding of state institutions, student debt is at worrisome levels. And then the Republicans say that because of student debt no one should take classes that allow them to create, or write, or enjoy the freedom of thought. Classes like that are luxuries, apparently. Institutions are turning tenure track lines into poorly paid adjunct positions. I could go on. My fear is that the liberal arts—the structure of thought that, as my friend Dave likes to say, gave us luxuries like democracy and science—will be preserved only for the rich, while most people will be given narrowly technical educations and expelled into the lower reaches of the vanishing middle class. I fear that genuine mass higher education will turn out to have been an historical aberration, beginning in the 1940’s and ending sometime around 2030. But I think people are beginning to push back. I hope we are.

What kind of students do you teach? What do you teach them? How do you teach them?

My students are pretty great. Case Western Reserve has traditionally been best known for its strengths in the sciences, but students have a lot of interest in literature and the humanities. I get a lot of English/Biology double majors, English/Computer Science. They tend to have flexible minds. Plus they’re almost impossibly well-prepared. I remember what I was like as an undergrad…well, you can read about it in White Out. The basic question I ask in my classes is: What does literature know? We try to bring literary knowledge into contact with psychological knowledge, economic knowledge, historical knowledge. I’m not interested in applying models from other fields onto literary works, but in developing a vocabulary for describing what literature knows. This week, for example, we’re looking at how the early 70’s Soviet Science Fiction novel Roadside Picnic created a template which the culture used to process the Chernobyl disaster.

What jobs did you work before academia?

I was working for a company that repossessed riding mowers when I applied for graduate school. By the time I learned I’d gotten in, I’d been fired. I’ve also been fired from a hardware store, an electrical contractor, a painting company. I actually painted the inside of a jail I was later incarcerated in. I got fired from Domino’s Pizza, and an office attached to a factory that made masking tape. I think it was masking tape.

Do you think you will work in other professions anytime in the future?

I hope not.