Where I’m Bound

21.04.16

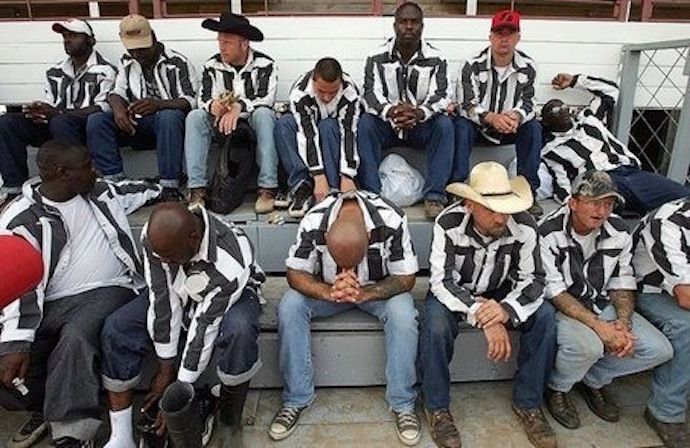

Image via HBO’s Sweethearts of the Prison Rodeo

I. On the Train

The conductor hasn’t seen the woman in Roomette 9 since yesterday. “I hope she didn’t die on me,” he says.

I make an appropriate face. He answers it with an assurance that she definitely isn’t dead: “She’s still sleeping. Or drunk, one.”

This exchange does not signal a more general camaraderie between us. An hour later, when I ask where the bathroom is, the conductor draws a heavy sigh at having to explain that there is a toilet and fold-down sink in my roomette. I suspected as much but couldn’t find any toilet paper. The conductor hands me three individually wrapped Rollettes of Soft Spun Personal Tissue and I return to my chamber.

I’m headed out from Atlanta to New Orleans by train, then renting a car to go to Baton Rouge, then to Louisiana State Penitentiary, more commonly known as Angola. Angola is the largest maximum security prison in the United States. Before there was a prison on that land, the 18,000 acres were used as a plantation, and it’s named after the country where the slaves came from. The inmates still work in the same fields, and since 1965, they—or at least a handful out of the 6,400-plus of them incarcerated there—compete in a rodeo on the prison grounds. The rodeo is now held twice a year. The stadium seats 10,000 spectators. I will be one of them.

A train on the opposite track rolls by. It will not end, and I can tell by the bars of light that flash between cars that I’m missing the finest landscape of the whole journey.

The seat I’ve chosen among the four in my compartment, between the grimy window and what turns out to be the hidden toilet, faces east. When I look up from my book, I can see everything as we pass. We. I paid extra for the privacy of a roomette, but the first-person plural is unavoidable when it comes to transportation. We’re landing shortly. We need gas. Are we there yet?

As we leave Atlanta, there is a sign for the Douglassville Boxing Club. Then we pass a plain cemetery that nobody visits. Then a thrift store with a sign that says, “If we don’t have it, you don’t need it.” It sounds like a dare.

The first time I took Amtrak to New Orleans, I was fourteen years old. It was a literary occasion. Planted happily in the club car, I wrote a short story about a man, a recovering alcoholic, headed by train to New Orleans for his estranged daughter’s wedding. A year before, I’d gone directly from writing stories about girls who found magic pennies and rode dappled grey ponies to writing about nothing but sad drunks. I watched a lot of Cheers. I wore reversible chambray vests that my mother sewed. I would tell anyone who listened why capital punishment was wrong. My favorite movie was Leaving Las Vegas.

We pass storefronts. In Bremen, there’s the Lion’s Den Tattoo Parlor, Fluffy’s Cupcakes, and Lady Bianca’s Unique Boutique. Southern sweetness and the kind of rebellion that nobody really minds. Bremen could be the setting of Steel Magnolias.

After Bremen are trees. The leaves haven’t turned, but the sun is out, energetically splashing the pines.

Tallapoosa is more of a Johnny Cash town. Pizza Buffet. Curves. Tallapoosa Gun & Pawn. CVS. Then a vacant brick building above which a sign reads GUNS. As if to prove I’m getting closer to Angola.

Come to think of it, Tallapoosa is mentioned in a Johnny Cash song. The name comes midway through the small-town list in “I’ve Been Everywhere,” in the verse after the “I’m a killer” chorus. Texarkana, Monterey, Fairaday, Santa Fe, Tallapoosa, Glen Rock, Black Rock, Little Rock.

The same year I wrote the story about the alcoholic dad, I saw Merle Haggard in concert for the first time. He was and is my favorite singer. My brother, a purist, tried to convince me that most country music, Haggard’s included, was over-produced. He bought me a Johnny Cash box-set to steer me right. I didn’t listen to it enough, not by his lights anyway, and soon he repossessed it.

We speed past a billboard for Elijah’s Barrel Pell City AL. Curious, I google the name. Turns out to be another thrift store, but the reviews are fascinating, and sharply divided. One praises both the aesthetic and the attitude: “With relics from times past as their decor, it seems you can leave behind the rush of today. The employees are extraordinary and they have no problems with children.” Another is framed as a redemptive personal narrative:

When i first moved to this town I was a single Mom who left a abusive relationship.. The owner was so nice to furnish me & my children with clothes and appliances for my home… I Think she is a wonderful Christian woman I will never forget her kindness. I am doing much better now .. I try to help others as an example of her kindness.

This good Christian image meets something well beyond skepticism from other quarters. There are accusations of racism and perfidy: “These people make fun and talk very badly about black people and minorities. The owner takes donated antiques to her two story home and decorates with them. These employees have no decent drinking water at work, no paper towels to clean hands, and no toilet paper unless donated.” Whiffs of the occult: “I heard chanting from some of the workers whom seemed to be full of somekind of crazy being.”

And most damningly, if only because the alliterative detractor relies on research yet elides the particulars of his/her findings:

Elijahs Barrel is full of behind the scenes secrets,These people call themselves Christens but they are completely far from it. They do not help as they promise to do but instead pocket the money and use it for their personal uses, after doing an background check on these people after hearing different accusations I did find out a good many things they have not come out with. I think a true christen does not lie,cheat and or steal their way they are ones who does gods work seems these people need to reread what Christanity really is before claiming they are.

If I’d read those reviews in eighth grade, I would have started a novel set in Pell City, filled with this kind of mean, pettish, small-town slander. I’d been confined since birth to an artless world of safety and abundance and goodwill. Nothing about my life felt literary the way Elijah’s Barrel would have. I don’t like to think that I still classify the world in those terms, and yet here we are. I’m on a train, staring out the window dreamily, on my way to write about a rodeo at a prison.

We pass the Catfish One Support Center. Lots of possibilities come to mind.

At lunch in the dining car, I’m seated with a pair of blond siblings headed to their grandmother’s house. The younger one takes up more space on the little bench they share across from me. He’s loud and pert, and affectionate toward his sister. He wants to know when her boyfriend will “ask Dad” for his blessing so they can get married. “I don’t know,” she says, thoughtful and assured. “Soon.”

They will have disembarked by the time we cross over Lake Ponchartrain. The water is glossy and real blue. The sun sinks behind a long stretch of faint pink clouds; there are sailboats and seagulls; bamboo fronds wave in the foreground. I’m on the better side of the train.

We turn sharp just as I get a last glimpse of the sunset, by now an earnest red. Ahead I can see the final stretch of tracks before we reach New Orleans.

I once had an argument about Johnny Cash with a houseguest visiting me in New Orleans. It started with my favorite trick question: “How much time did Cash spend in prison?” The answer being, not a single day. This rankled my interlocutor. How dare he speak for the prisoner as if he knew that kind of despair? I said that he was making a dangerous argument—so much of art would be thus invalidated. So be it, said my houseguest.

Merle Haggard was a real hobo. He hopped freighters to evade the law years before he wrote “I’m a Lonesome Fugitive.” Eventually, he did time in San Quentin. I like to remind people that he was in the audience when Johnny Cash performed there in 1958. You can hear the rumble of the crowd in the lead-in to the eponymous song, when Cash asks if any guard “who’s still speaking to [him]” would bring him a glass of water. Maybe there’s no picking out Haggard’s honeyed baritone amid the inmates’ whistles and shouts, but he was there, and afterward he felt so good about music that he joined the prison band.

There will be prison bands playing at the Angola Rodeo. One bandleader will request that “the ladies” come to the front and dance to a song about ladies shaking their butts. No ladies will comply.

II. New Orleans to Angola

Time is not precious to me today. I have to get to the Hertz office by closing time at 1pm; all I need to accomplish before that is brunch with an old friend. Joey says he’d never been to the rodeo, but his high school psychology class took a field trip to Angola. He remembers the welcome center, which displays, as I would soon see for myself, a selection of the contraband that guards confiscated over the years.

After brunch, we drive past my old apartment on Magazine Street. The summer I lived there, a year after Katrina hit, a ring of cross-dressing thieves terrorized the newly reopened boutiques along Magazine. They would rush in carrying designer purses, fake babies, and real toddlers, cause a scene, and run out with armloads of glittery, glamorous merchandise.

Joey encourages me to take River Road to Baton Rouge. “You can see all the plantation houses.”

The Hertz employee who helps me says he’s headed to Baton Rouge this afternoon, also. The only time he’s taken River Road was during hurricane evacuation. He’s never been to the rodeo, either. He doesn’t know why not. The long drive, maybe. “It’s funny, actually, because my father’s there.” Meaning, incarcerated in Angola. “So he’s there every year.”

By the time he’s gotten the keys to my rental, he’s nearly convinced himself to go. I mention that tickets are probably sold out. He doesn’t seem disappointed.

I drive on the wrong bank of the river. It’s the ugliest stretch of road I’ve ever seen. The levees block any view of the waterfront. For hours, I bend around and under the giant mechanisms of oil refineries. The road is deserted except for me. I thought I’d find a sweet Cajun restaurant for a late lunch, but there’s nothing but metal and fumes. About twenty miles from Baton Rouge, I give up and find the main road.

III. Before the Rodeo

I’ve never been to a prison or a rodeo before. The event happens on a Sunday, so as I drive up the long road that winds along the river to Angola, I listen to a sermon on the radio. The crux of it: if you can’t say for sure that you’re going to heaven, then you won’t. Because you don’t have faith that Jesus saves. On the other hand, if you do know (like the preacher’s mother said she did), then you’re good. This seems encouraging.

Later the sun will come out, but right now it’s cold and windy. In Baton Rouge, I had French toast stuffed with slick strawberries and cheese-like matter, the kind of breakfast food that nobody who doesn’t own a B&B has ever thought of cooking. Even or especially after the drive, the meal sits heavy. When I park and enter the prison gates, all I can see are stalls selling Louisiana-style carnival fare: funnel cakes, jambalaya, snowballs, corndogs, gumbo. Refreshments are sold by prison organizations: the Drama Club, Men of Hope, the Camp C Concept Club. The Sober Club of AA deals in bacon dipped in chocolate, replacing one vice with two others.

For now, I can’t eat again, but I survey everything and plan my afternoon meal. I want dirty rice, and later, I’ll get it. Thickly larded with pork parts and sausage, it’s hot and oily and there’s too much of it. The official word is that the food sold in the stalls comes from prisoners’ family recipes. Maybe. Maybe.

Most of the rodeo grounds, outside the arena itself, is covered in craft tents. This is probably the most surprising part of the day: the sheer volume of handiwork made by prisoners, for sale at the rodeo. There are enough rocking chairs for sale to furnish every mountain resort in Appalachia. Little models of Cajun cabins, or maybe they’re fish shacks, with little signs that say “Thibodeaux. Keep Out!” Tablesful of woodwork festooned in LSU and Saints colors. I wonder how many people’s full-time job it is to order and supply the prisoners with all the raw materials, leather and fuel and canvas and knives and clay and most of all wood, needed to make these thousands of objects. And then there must be instructors, and people who manage the money from all the sales that day, which the prisoners apparently get to keep.

Some prisoners, identifiable by their striped shirts, man the booths, while others watch from a sort of narrow, fenced-in bullpen around the edges of the tent. I wonder: do they take shifts, or whether the ones within the fences are considered too violent to mill about among the general public, or whether they’ve simply lost the privilege or never earned it. One man, who looks to be about ten years younger than me, draws my attention to the metal jewelry he’s selling. “You look like a butterfly kind of girl,” he says through the bullpen fence. I demur but ask where he’s from. Shreveport. I tell him I’ve never been. “We’ve got everything in Shreveport,” he says, but doesn’t provide examples. I guess everything needs no elaboration. When I say I’m from Atlanta, he mentions that he had plans to visit, “But then I got incarcerated. Maybe when I get out, I’ll go to Atlanta. I might need someone to show me around.” He winks. To this, I give no reply, and he doesn’t need one. He laughs easily and says from behind the fence, “We’ll just see when that time comes.”

The next day, I’ll find out that the crafts fair is the main draw for most people. Many come every year and buy enough to fill trucks, vans, trailers. There must be some kind of resale value, because surely these people do not keep decorating their homes with more and more Angola handicraft. There must be a big market for it. Later, back in New Orleans, I buy a used copy of John Cheever’s prison novel, Falconer, and it mentions “a display of the convict’s art with prices stuck in the frames. None of the cons could paint, but you could always count on some wet-brain to buy a vase of roses or a marine sunset if he had been told that the artist was a lifer.”

I talk to a painter about his paintings. None of the paintings for sale at Angola document prison life. Mostly, it’s animals, landscapes, and boats. Same goes for the pyrography, or wood-burnings. One artist eagerly describes how he made the things he made out of wood and fire, but I don’t buy anything from him or anyone else. There’s just too much of everything, and I don’t really want a memento of this. I know I’ll never want to come back, either, though I can’t say exactly why not.

At the time I took the train to New Orleans, passed by Elijah’s Barrel and the Catfish One Support Center, and drove myself to the Angola Rodeo, where convicts wear stripes and ride broncos and fight bulls and sell wooden handicrafts, I’d never made a mistake that cost me even a day of freedom. Never been grounded or sent to detention, never censored, never silenced. But about three months after I visited Angola, I had what’s known, in literary dialect, as a nervous breakdown, and I found out that there’s nothing literary about it.

IV. Three Months After the Rodeo

At first, your hands are in restraints. You don’t remember why, for your thoughts are too excited to examine the past. You beg to be released. You know there’s been a series of mistakes going back several days, but you don’t recall that you made the first and most catastrophic one, even though the men in uniform keep reminding you what you confessed. You blame the men in uniform. They keep leading you through perfunctory procedures without releasing your hands. Everything is some kind of test you’ve already failed.

You beg for food. “Just a little sustenance,” you say, choosing the unusual word to make the request sound more thoughtful. They laugh. They also laugh when you sing to yourself. Time passes, and they agree to your request. Softened, or exasperated, they fetch a paper bag of food and place it on your lap. It is a nearly impossible distance from your mouth. You twist and maneuver your bound hands to open the bag and pull out a sandwich. You crane your head painfully toward your hands which hold the sandwich. It is the best sandwich ever. You drop the paper into your lap. Twisting, maneuvering, you pull an apple from the bag. It is the best apple ever. You eat fast. Vitamins and proteins surge like music into your head and legs and around your twisted hands to your fingertips. Then there is nothing left in the bag. There is trash in your lap for some time.

You are in hell. You are covered in cuts and bruises of unknown provenance. You blame your parents. They did not keep you safe, the way they said they would. Neither did your friends. Nobody did. Right now, it has slipped your mind that your safety has been your responsibility ever since you became an adult. With responsibility goes freedom. Both have gone.

You stop fighting, you stop asking for things. That’s when they release your hands. Your wrists are red and deeply lined. They discuss where you’ll go next. One of two places. They choose, and with real kindness and concern they say to you that it’s the much nicer facility.

Outside, it is night, but a different night than before. You climb into a van. It’s just you and the driver. For thirty minutes, you sit in the van. Downtown whips by, and then you’re on an interstate. You can’t tell which one. It doesn’t matter. Wherever you’re going, there will be a bed for you.

Check-in takes most of the night. You can’t go to bed yet because your bed hasn’t been assigned. You can’t rest your body yet because your body hasn’t been checked for hidden things.

Here, nobody laughs at you. This is lucky because you are all out of jokes. All you have left is the wherewithal to sleep, which is also lucky because that’s what you most lacked in hell.

It is almost morning, but not quite. Bed assigned, body checked, you sleep. Then comes morning, and more sustenance: chocolate milk, bacon, a biscuit, and stiffly scrambled eggs sitting in a little pool of water. You eat slowly and lustily, for your hands are free and you are in heaven. Someone talks to you while you eat. She says the red coat you’re wearing reminds her of the little girl in Schindler’s List, the one who screams “GOODBYE, JEWS” with hate on her face. You don’t know what to say. Then the woman asks why you’re here. You tell her the truth. A year later, you stuff the red coat into a trash can.

You are given a fresh change of clothes. You make a phone call to your father. You tell him that you are okay, and he sounds very happy to hear it, so happy that you wonder if he’s ever been so happy before. You want to cry. Instead, you hang up and join everybody for compulsory activities. Smoke breaks are not compulsory, but you realize within a few days that it’s the only way to get outside. In between activities, you sleep.

At night, after dinner, there is an optional activity: karaoke. You watch as someone hams it up, and you hear everybody’s laughter. You realize how different you are from the others. You can’t laugh. You can’t relax your face and enjoy the music like they can. That’s when you become anxious. It is not nice to be in heaven anymore. You don’t know when you can leave.

The next day is better. Your parents visit. They are so happy. It won’t be long, they say, before you get to go back home with them. You point out a few of your new friends to them. That night, after all the visitors leave, and after dinner, you work a puzzle and pass around a Bible, reading versus aloud and praying silently. These activities, quiet and solemn, keep you calm. Now you begin to feel a kinship with the others. You decide you want them to remain in your life after you leave. It’s only after you leave that you’ll realize you don’t want that at all.

You continue to relish every meal. The others tease you for enjoying the bland, institutional food, but you don’t pay any attention. Your memory of hell is sharper than theirs, you think. They should be glad for the dry chicken and anemic vegetables, the puzzles with missing pieces, and the small, hard, warm beds. Instead, they are very sad. They miss their families and their freedom. Unlike you, they’ve been in places like this before, and now they’re back. You realize that the stakes are much higher for the others. Guilt and fear has ravaged them.

You can ignore their teasing, but you can’t ignore their despair. It is not yours. You have hope. The people in charge see yours as a special, lighter case. A blip. Your time here is the result of a mistake that you almost didn’t make, and that you won’t make again. Tomorrow, day four, you get to go home, and nobody expects to see you there again. Your dad tells you it’ll be something to write about someday.

V. At the Rodeo

Nothing bloody happens, nothing wild. The inmate-athletes wear a modern sort of armor, so even when a bull digs them up and sends them flying toward the fences, they spring back up and trot to safety. Nobody’s ever been killed at the rodeo, but more prisoners will die within the confines of Angola, serving out life sentences, than any other prison in the country, maybe the world.

The events have different names—Bust Out, Bull-Dogging, Wild Cow Milking—and the rodeo program describes the premise of each in a few concise, specific sentences, like: “Teams of inmate cowboys chase the animals around the arena trying to extract a little milk. The first team to bring milk to the judge wins the prize.”

I’m pretty sure nobody extracts milk, but I could be wrong. It’s hard to see what exactly is happening in the arena. The events run together: big animals, skinny prisoners, hijinks. It is impossible to keep score or identify a favorite among the contestants. They all fail in similar ways. They aren’t professional cowboys. They haven’t practiced.

The Bull Riding event description advertises how green the competitors are: “This dangerous and wide open event is what the fans come to see. Inexperienced inmates sit on top of a 2,000 pound Brahma bull. To be eligible for the covted ‘All-Around Cowboy’ title, a contestant must successfully complete the ride (6 seconds).” As far as I can tell, nobody manages.

Around me, people watch, and toward the beginning there are some sympathetic Ahs and Oohs whenever a steer bucks a man from its back. Mostly, though, the audience seems underwhelmed, more interested in the giant blooming onion in their right hand and the fried pie in their left than the spectacle playing out in the arena. It’s no wonder. Spectacle is a strong word for this bit of pageantry: the production value purports to be high, but it’s thin around the edges. Even Convict Poker, which I anticipated most eagerly, comes off as stagey and tired. The cards are the size of paperback book covers, and there aren’t any poker chips. They don’t bet or play their hands. They wait for the bull to pick them off one by one.

As a young equestrian, I rode hunter-jumper, and I’ve been to the racetracks a handful of times. In those contests, the horse and its rider or jockey are a team. They communicate. They cooperate. Breeding, training, and appearances matter a lot. At Angola, the inmates face off against the broncos and bulls and the other inmates. There’s no strategy, no nuance, none of the seriousness of other equestrian sports. It’s broadly comedic.

Maybe, if I knew the rodeo like I know tennis or baseball, I could discern more patterns, or spot a raw talent. But the women’s barrel racing portion is an interesting counterpoint to the rest of the messy show. It’s the single event at Angola with professional athletes. Here, alone, the rider and her animal move as one, bending as close as possible around each barrel without toppling it. I learn fast, the way you do when you watch Olympic figure skating or diving. In just a few minutes, you can easily see which movements are lean and which are flabby. You can identify the elements of style and form that distinguish the most elite competitor. It’s intuitive. It’s beautiful. It makes me wish I was at a real rodeo.

The story I’ll end up telling the most to people back home has to do with a small team of monkeys who ride sheepdogs and herd baby rams onto a giant truck. Their owner, a man in a sparkly suit who’s been brought in from the outside, kneels down and faces the crowd. He introduces the animals by name and tells the crowd that he’s living out his dream by training these rough riding monkeys, and we, the crowd, are now a part of that dream, and we should go forth and live out our dreams the way he is.

Angola Prison has an accredited four-year college on premises. One prisoner just received a degree in divinity from a seminary in New Orleans. Notorious in the past for abuse and corruption, Angola now enjoys a sterling reputation. A Christian reputation. The rodeo raises hundreds of thousands of dollars for Christian programs at the prison. Originally, the event was just for the prisoners’ entertainment, but within two years, the general public was invited to share in the fun. It’s been a huge success.

All the promotional material encourages you to believe that the rodeo is a big treat for the prisoners. The dust in their eyes, the rush of air, the anger of the animals—this is their day to indulge in and release their passionate, criminal energy. They get to pretend to be cowboys and outlaws at once. They get to put on a show.

Image via Atlas Obscura

VI. After Angola

When a prisoner dies at Angola, unless a family member claims his body, he will be laid to rest within the confines of the prison property, a giant expanse of farmland that was once a plantation where slaves picked cotton. His corpse will be enclosed within a coffin that his fellow prisoners built in the woodshop. The coffin will be carried to the burial site in a hearse that prisoners engineered. There will probably be song and prayer. Maybe a friend will ask God that the soul of the departed escape from Angola, since his body never will.

I went to the Angola Rodeo to write about it. On the train, in New Orleans, and at the prison, I thought about what I would write. A lot has been written about Angola and its rodeo, but plenty of people still haven’t heard of a prison rodeo, so I figured I could still add to the literature. I thought about what my angle would be.

There is a lot to say about exploitation and modern gladiators and the politics of the prison-industrial complex and the ghosts of prisoners at Angola and the ghosts of slaves. There’s a lot to say about America, and how our national cinema is surely more obsessed than any other with prisons, and incarceration, and chain gangs, and escape routes, and convicts who find redemption and ride into the sunset. An American Studies major could write a killer dissertation about the union of these twin archetypes, the prisoner sentenced to life and the cowboy whose Wild West has no fences, no limits or borders.

I’m not sure I’m qualified to write authoritatively on any of those complicated political and cultural meanings of the rodeo. On the other hand, I don’t know whether it’s appropriate or responsible to tell my story of forced hospitalization within a story about watching a prison rodeo. My hell was not bottomless. I was not convicted to a life sentence or anything like it. Still, I haven’t been able to think about Angola without thinking about my own very brief confinement, but not because the experience gave me access to the dreams and lives of the men serving time at Angola. It gave me a sense, I think, of my own arrogance when I went to the rodeo, intending to write about it.

I was no Merle Haggard, even though I was the one in the audience. The rodeo was something to observe with gentle dispassion, wit, and political acumen. Unlike Johnny Cash or John Cheever, I didn’t have the wherewithal or the courage to imagine what it was like down there in the dust among the other men and the angry animals, for just four days a year, even though I used to ride horses, and knew full well how, when they get going really fast, you catch a breath of something eternal, but you can’t hold onto it, and once you stop you’ll never be so happy and free again. I didn’t understand the value of a smoke break or how ghastly Karaoke Night could be.

I didn’t notice the sniper towers surrounding the gates of Angola, and I paid no attention to the guards. Though I once loved to write stories about shameless drunks who wanted to die that way, I didn’t know that the exact moment you lose all inhibition, and begin what feels at first like a free-fall into grace, that’s when you’ll be stopped and contained, because you’ve become unacceptable. At the time I went to Angola, I’d never had a good reason to fear death, or hell, or heaven. I didn’t know four days can last forever if you let it.