When I Was Younger, I Too Saved the Earth Many Times: A Review of EarthBound

08.05.14

EarthBound

EarthBound

Ken Baumann

Boss Fight Books

$14.95 / 191 pages

EarthBound by Ken Baumann starts with a reconciliation. For the first time in a year, he calls his brother to talk about the video game for which the book is named.

The men are immediately able to recall hours of shared play, tactical challenges, images. This is fairly representative of the social power of video games for a certain cross section of children. You could argue that sports or stamp collecting or whatever offer the same benefit but, with video games, shared experience is literally packaged in a box.

Other hobbies do not offer the same persuasive, captivating goals.

For me, video games were a way for my brother Aaron and I to be social together when we so often pummeled each other until one of us (usually Aaron) was left in tears, they could be a reason to invite friends over when I was often so filled with social anxiety that I had no clue why anyone wanted to hang out with me.

My family didn’t get our first video game system until I was 10. It was an N64 addressed to both my brother and I from Santa on Christmas morning in the year 2000. Included with the system were our first three games:

-

The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask

-

Star Wars: Rogue Squadron

-

Super Mario 64

I had been playing video games at friends houses for years and was already obsessed with The Sims and Pokemon, but games were largely a social excuse and spectator sport for me.

When we were stuck indoors during typhoon season in Japan, I remember watching Dad play MYST on what must have been a Power Macintosh.

Even after we had our own Nintendo system, I still mostly just wanted to mess around in the virtual worlds. I would half-heartedly attempt dungeons in Zelda before calling my friend Kenny over to beat them for me so I could continue riding around on Epona, chasing chickens, swimming with the Zora. Really, just doing anything but moving the plot forward.

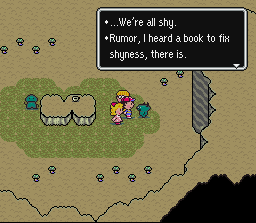

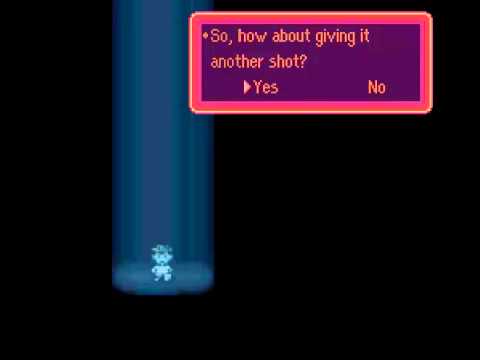

In contrast, Baumann’s brother taught him to be a student of the grind. Finishing many classic video games is all about just pushing through and leveling up until you are strong enough to defeat the final boss. I did not begin playing these sort of games until I became an adult, so my reference points are different than Baumann’s, but I wanted to relate, so I began to play EarthBound while reading it.

Early on in the book, Baumann warns the reader that, if they haven’t played the game but want to, it might be a good idea to stop reading in order to experience it first.

This is a good recommendation for people who are sensitive to spoilers, but I actively seek them. Reading EarthBound in tandem with playing created a sort of a longing for someone else’s nostalgia. I delighted in recognizable moments not because I had seen them long ago, but because I had read about them and was finally able to pair a perfect visual with what had previously been described to me.

Baumann deftly balances personal narrative with art criticism, drawing parallels between his life and the story of the game’s main character, Ness. At its heart, both the book and the video game could be seen as narratives about privilege and the ways in which capitalism shapes social relationships.

It takes a lot of material resources for a kid like Ness to save the world (regular payments from Dad, hotel stays, overseas travel, increasingly fancy baseball bats) and to be a child actor (rent in LA, headshots, travel). Game and book both admirably confront this. Ness is made fun of if he can’t pay for a hotel room, Baumann balks at the current going rate of a studio in the building he lived in as a teen during pilot season.

These parallels are most apt in the relationships between the child characters (Baumann, Ness) and their parents.

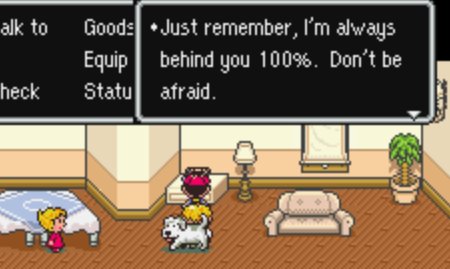

Both he and Ness had absent fathers, Baumann’s stayed behind to manage an auto repair business when he, his mother and sister moved to LA so Baumann could pursue acting. Ness’s is ambiguously absent and only available by phone either because of work or he is on the run from some sizeable debts. In spite of this, Ness’ father constantly sends the hero large sums of money.

I cannot think of a single video game with a child protagonist that does not feature daddy issues in some way. Whether they are missing and unmentioned as in the Zelda series and Chrono Trigger, or ambiguously supportive but absent like in Pokemon and EarthBound, few video game children have the privilege of a rich relationship with their fathers.

More interesting than the absent fathers though is the implicit trust both sets of parents place in their boys. They spend massive amounts of time unsupervised and, despite experimentation with illicit substances or associating with the wrong crowd, both boys emerge a little world weary but with wholesomeness still in tact.

In each of the stories, no one seems to die. Baumann survives a perforated intestine as a consequence of his Crohns disease; Ness defeats the world’s evil and is left unharmed (at least physically) because his soul has been placed in a metal body. Both boys return to their families.

Even the villains in Earthbound don’t truly die. Vicious dogs are simply made “tame” by Ness’ attacks, zombies go back to being “the dust of the earth,” gang bosses are left with deflated egos.

This was one of the elements of the game that was most charming to me. Even when faced with terrifying monsters, Ness and his friends do not wish the pain of death on them, but knocking a little sense into them isn’t out of the question.

The rosiness of EarthBound the game’s tone is what makes it so lovable, but the rosiness of Baumann’s book is its most significant downfall.

Baumann is a talented writer with a strong critical voice in his writing about acting and culture on his blog. He is clearly capable of employing a critical eye, which is why it was so disappointing that he barely breaches the surface of EarthBound’s faults.

It is supremely fucked that the primary weapon of the game’s sole female playable character is a frying pan. The female NPCs Ness and company encounter are exclusively bound to service roles: soap opera-obsessed housewives, nurses that act as receptionists instead of practicing medicine, sexy zombies used as bait, harassed elevator operators, fawning fan girls, and forgetful sisters, to name just a few examples.

Baumann is briefly critical of the racial homogeneity of the NPCs, who are mostly white and blonde, but this passes quickly.

The book is strongest where Baumann creates a collage, expanding his personal narrative with external texts, drawing in everything from poetry to interviews with the game’s translator and ad copy written by Shigesato Itoi.

While EarthBound has its problems, it is a well-structured, sincere and compelling exploration of social relationships created around tech. Academia’s ignoral of games as being worthy of criticism is careless at best and outright classist at worst. I sincerely hope this marks the beginning of a new future for video game writing.

——————–

Frances Dinger works for an environmental nonprofit and APRIL, an annual festival of independent publishing in Seattle. Her work has been published in various places online and in print. She tweets @f_e_dinger.

EathBound by Ken Baumann is now available from Boss Fight Books.