What Makes Us Human And Not God: A Review of Vi Khi Nao’s The Old Philosopher

16.06.16

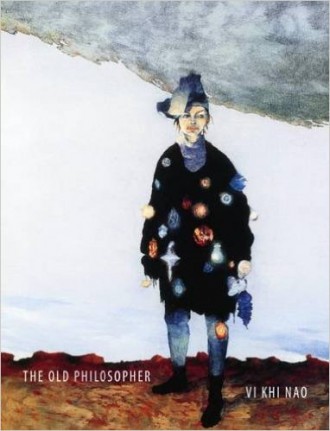

The Old Philosopher

The Old Philosopher

by Vi Khi Nao

Nightboat Books

73 pp / $15.95

Reading experimental poetry can feel like driving in a traffic jam: you read one line over and over, trying to “get” it, tentatively proceed to the next line, feel even more like you are drowning in blank confusion, flee back to the previous line, read the two lines together a few times to see if their meaning can perhaps be “unlocked” that way, then go back to reading the first line alone because maybe you got it all wrong the first time; eventually, feeling none the wiser, you look up at the clock and realize a half-hour has passed and you haven’t even reached the third line yet.

Fortunately, Vi Khi Nao’s debut poetry collection The Old Philosopher, though ravishingly experimental, is not like that. Nao’s poems are eminently readable, having a brisk, breezy, informal voice (“See ya around, pancake faces,” the speaker of one poem says slangily) and being widely spaced on the page in a way that invites the eye to partake. Reading her words, you find yourself turning pages at a rapid clip.

There is a worldly, cosmopolitan sensibility at work here: in their use of line, image, and irony, Nao’s poems are reminiscent of modernist French poets like Laforgue and Apollinaire. At times, they also evoke Eastern European surrealists like Novica Tadic, as in the case of the claustrophobic and terrifying dramatic monologue “A Cuban Bay of Pigs,” which begins, “When I first met her, her face was hollowed out, like // a soggy tree carved from the center with a metal // spoon….” The poem goes on to describe how a despot turns a woman’s head into a pinata because “she had the face of history and to me, it seemed, to // get rid of her face was to get rid of history.”

The poem “Today I Lost My Hat,” which chronicles the events of the day of the speaker’s grandmother’s death, gives off an especially strong European vibe:

Morning: I hung my wet sock on the giant coffee maker. A

co-worker offered his large winter glove as a makeshift

sock. In two hours, the warm breath evaporating out of the

throat of the sock steamed my toes.

Brunch: When the sun did not show up for work. When

there was much dying to do….

The theme of work (“the sun did not show up for work”) and the motifs of offices and co-workers recur insistently in Vi Khi Nao’s verse, reminding us that a full understanding of the human condition cannot omit labor economics, that the political systems of capitalism and communism have shaped and are continually shaping our experiences. “Today I Lost My Hat” ends with a Laforguian exclamation, capped with a Laforguian exclamation mark: “How death makes one suffer!” As in Laforgue’s work, this line is wrapped in self-awareness: the poet is fully aware of how inadequate this conclusion is, how unhelpfully general and abstract, and yet wants to make the point that our responses to death and suffering are defined by their inadequacy, that this is what makes us human and not God.

Another poem with strong French resonances is “My Socialist Saliva,” which begins by recounting a memory of the speaker’s childhood in Long Khanh, Vietnam: “My seven-year-old face pressed onto the serene field of my mother’s back // As she rode her motorcycle through the red earth // Flanked by rubber trees….” The poem goes on to complicate this pastoral scene by narrating how: “There were times though when the Viet Cong // Came through my grandmother’s grapevine // And took my mother’s sewing machines….” The poem ends with a conversation between the now Americanized speaker and her Uncle Binh “eleven months ago”:

He said if I ever get depressed in the States and want a different kind of oppression

Call him and he would buy me a ticket home

And we could inhale oyster shells together under a blanket made of intestinal veins

A blanket the communists would stitch with the needle of their greed

I suppose I could go on

That final line, “I suppose I could go on,” is quintessentially French Modernist in its jadedness, in the way it breaks the fourth wall, in the way it resists tying the story up with a neat little bow. With that line, Vi Khi Nao is rejecting an outdated mode of storytelling; as if with a shrug that says “Haven’t we been here already?” she is turning the conversation back over to the reader, forcing us to share the task of considering how to move the genre of Vietnam literature forward without retreading the same old tropes we all already know.

The book ends with “Skyscraper,” a 12-part prose poem sequence that sings the fragility of the human body, dramatizing the ordinary tragedy of obscure human lives as embodied by a sick seamstress (perhaps the speaker’s mother, or grandmother?) who collapses and dies one day in the shower:

While the rain washes the windows, the sky-

scraper collapses. For 2 hours and 20 minutes

the pores drink in the scent of a memory, a

portal between oblivion and permanence before

the ambulance comes…. In the binary world, in the

world with God, rain and skyscraper take turns

wearing each other’s clothes.

In this deeply moving poem, the poet plays games with proportions, shrinking down large things while magnifying small things (pores, blood vessels, soap suds). This, the book seems to say at last, is the culmination of the experiment; this is what experimental poetry can do at its best: make us see from all sides at once, like a cubist painting, the beauty and frailty and integrity and loving bonds of human lives.

—————–

Jenna Le‘s book reviews have been published in such venues as The Rumpus, Pleiades, Poetry Northwest, and The Pharos, while her poetry has appeared widely, including her two published poetry collections, Six Rivers (NYQ Books, 2011) and A History of the Cetacean American Diaspora (Anchor & Plume Press, 2016).