We Can Only Expand the Boundaries When We’re Up Against the Ropes: Gabrielle Calvocoressi and Brandon Scott Gorrell

24.09.09

Gabrielle Calvovoressi

Gabrielle Calvovoressi

Apocalyptic Swing

96 pages

Persea Books

(Sept. 15, 2009)

Brandon Scott Gorrell

During My Nervous Breakdown I Would Like to Have a Biographer Present

88 pages

MuuMuu House

(June 20, 2009)

At the risk of being reductive, there are two categories of contemporary poets: those who receive laurels, tenure, grants, fellowships and publication in perfect bound journals and those who publish on websites and tiny, obscure presses and promote their books primarily through Facebook, Twitter and blogs. The longstanding divide between academically sanctioned poetry and avant garde writing has been exacerbated in part due to two factors: the proliferation of creative writing MFA programs and the growth of internet publishing. These collections from Gabrielle Calvocoressi and Brandon Scott Gorrell are each in their own way an example of these two countervailing trends.

According to Edward Delaney’s 2007 article “Where Great Writers Are Made” in The Atlantic Monthly, the number of creative writing programs in America has exploded from 50 to more than 300 in the last three decades. This means that each year thousands more poets graduate with the expectation that, like their professors, they too will be able to make a living — if not by writing poetry — at least by teaching it. And yet the proportion of MFA holders who manage to find this type of full-time academic employment remains miniscule.

Meanwhile, digital publishing, print on demand, and social networking sites make it faster, cheaper and easier than ever to get one’s work published DIY. In contrast to the academic model, avant-garde poetry is part of a tradition that has always favored cheap-o publishing methods — such as the Xerox machine and its precursor, the mimeograph — and this branch of American poetry has largely embraced the possibilities of digital publishing. And so, to some extent, the number of participants in both of these two branches of poetry is more numerous than ever regardless of whatever readership contemporary poetry is able to muster.

In 2005, Booklist declared Gabrielle Calvocoressi’s first book, The Last Time I Saw Amelia Earhart to be a “tour de force collection” from “a potent new poetic talent.” Calvocoressi’s bio is the stuff MFA students dream of: the sought-after Stegner fellowship, a position as a lecturer at Stanford, a bunch of awards and teaching in creative writing programs. Gabrielle Calvocoressi’s writing is an example of a type of – for lack of a better word — popular poetry, primarily an extension of academic poetry. At the annual Associated Writing Programs (AWP) conference, conference attendees line up to have books signed by mainstream poets and tenured professors like Billy Collins or Mary Oliver, which is what passes for mainstream success in poetry’s Liliputian world. People enjoy this kind of poetry in part because it is easy to understand, although that is typically not its only strength.

Calvocoressi’s work was recommended to me, not by other poets, but by fiction writers, and I immediately understood its appeal. Generally, when fiction writers like your work, it means your poetry has just enough narrative juice to keep them interested. As an MFA grad and sporadic poet myself, I’m a little jealous of Calvocoressi’s success, but that doesn’t mean I can’t admit that she’s got chops. Her new collection, Apocalyptic Swing, isn’t within my area of interest, but it has a tight structure and a strong line of inquiry throughout.

Calvocoressi’s most notable stylistic choice is that she frequently writes in the voice of historical people, a technique that she used in Amelia Earhart and continues to use throughout her new book. Calvocoressi also has the courage and skill to write about the Big Stuff without becoming sappy: there’s a lot of God in this book, and some Sex, some things about Mother, and — juxtaposed against those themes — boxing. When talking about the ‘absolutes’ in life, boxing makes sense as a metaphor. Jacob may have wrestled with an angel, but Mike Tyson bit off a piece of Evander Holyfield’s ear and in return has become a 21st century sinner turned martyr: the guy who’s paid for our cultural sins of greed, sexual promiscuity, and excess.

Calvocoressi doesn’t write about Tyson, but in “Blues for Ruby Goldstein” she writes in the voice of a little known boxer nicknamed “the jewel of the ghetto.” After competing in the ‘20s and ‘30s, Goldstein went on to a career as a referee. The poem, like most of her work, is written in plain, unfettered language. It opens with a view of a ghetto neighborhood street at “sunset when the streets get/ quiet”

What does anybody

know about a body anyway?

It can take a worse beating than most

can imagine. You can get every rib broken

and your eyes punched shut and your kidneys

can bleed like you see at the butcher.

This smart shift from idyllic sunset to bleeding human kidneys is emblematic of another of the book’s signature techniques: alternating between beautiful, nearly maudlin passages to images of human brutality. As Goldstein reminisces on his brief boxing career, the poem occasionally slips into cliché: Goldstein, who was small for a boxer, says in the poem that he was “All heart. That’s what most little guys are./But that counts for a lot.” But Calvocoressi balances this with graphic depictions of punching, failing to punch, and even choosing to walk away from a fight before you get punched.

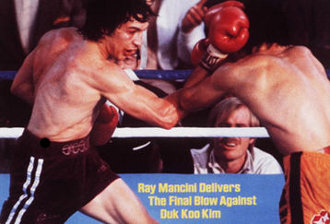

Calvocoressi’s other boxing poems perform similar maneuvers, slipping between violence and sweetness. “Box Fugue,” about the Korean boxer Duk-Koo Kim, who died after a fight with Ray Mancini, has some startling images – rain in Vegas, a mother with a gun shoved into her mouth (“all our mothers/have to die one day”), but then ends with the predictable line “We are all so beautiful/ with our face against the mat.”

“Temple Beth Israel” perhaps best captures Calvocoressi’s ability to skillfully balance predictable images with unpredictable ones. In this final poem she describes what she sees while jogging through her Los Angeles neighborhood, such as a boy “resplendent in his yarmulke and Lakers/ jacket.”These observations lead to a series of images and ideas that range from church bombings to the landscape of Southern California to the act of reading and when she stops and asks herself, “Does it make this less of a poem?” the question feels earned. Calvocoressi contains her Big Ideas and balance of images in a variety of unusual forms. I was surprised to see litanies, epistles and even a pantoum, a somewhat archaic form that frequently repeats lines; something I hadn’t seen since I was assigned to write one in grad school.

If Calvocoressi’s poetry leans toward something a lot of people will like, Brandon Scott Gorrell’s book, During My Nervous Breakdown I Want To Have a Biographer Present has more of the casual, not-giving-a-fuck attitude of an overly revealing Facebook status update. While aspiring writers might be jealous of Calvocoressi’s bio, Gorrell’s is more likely to sound all too familiar: “Brandon Scott Gorrell has been widely published on the internet.”

Nervous Breakdown belongs to a new-ish genre that might be called Internet Poetry, or Gmail Confessionalism, or Facebook Lyricism, or some combination of all of those things. The collection is published by MuuMuu House, a new small press helmed by the prankster poet and fiction writer Two Lin, whose own books have titles like Shoplifting from American Apparel, You Are a Little Bit Happier Than I Am, and Today The Sky is Blue and White with Bright Blue Spots and a Small Pale Moon and I Will Destroy Our Relationship Today. Although Lin’s persona as a smart aleck-y, chit-chatty writer can come across as abrasive, he’s a genuinely smart and funny writer and his dedication to small press publishing is not a joke. MuuMuu House is a relatively new venture; as of this writing, it’s only published two titles, but more seem to be on the way. For the most part, the poets published by Lin’s presses — he runs at least three of them — have a lot in common with his own style of writing, and I found some reminders of Lin’s poems in Gorrell’s. There’s nothing wrong with this: writer-publishers will of course be attracted to work that’s kin to their own and it can even give a publishing house the same familial feeling as a favorite independent record label.

While the cover of Apocalyptic Swing shows a closeup of a boxer’s taped fist: a literal photo that depicts something about the contents, Gorrell’s book has an abstract neon green starburst design. Inside this starburst are the words “anxiety”, “low self esteem” and “alienation” written like a motif from an 80s infomercial. While I realize that authors rarely have input into their own book designs, this image in many ways represents exactly what’s inside. These are poems that convey emotions and ideas in bursts, like short spats of furious typing. In fact, many of them sound exactly like that. Take the poem “gmail”:

I have urges not to check my email for a week so that when I

finally check it I can feel at least a minute or a minute and

a half of extreme excitement

I have gotten adrenaline rushes from situations like finding

eight new emails

That’s the whole poem and that’s probably a good thing because there’s no logical place for it to go from there. God, Mother, Etc. it ain’t, but there’s something emotionally familiar about it for many of us to be sure. Whether or not this kind of poetry can sustain one’s interest for an entire collection is, I suppose, up to the taste of the reader.

Gorrell’s is not a poetry of sophisticated diction, elevated thinking, or abstract concepts. If anything, the overarching theme here is of alienation through technology. The poems often fall back on talking about the speaker’s email, his blog, his loneliness, his alienation from others, returning to his email, his blog, and so on. It’s a book of cycles where the solution to emotional crises, depression and alienation keeps getting sought out online but is never quite found.

Not all of these are interesting poems on their own but they do function together as a collection. They frequently veer into irritating extremes of repetition but I think Gorrell’s doing something with that technique rather than just being lazy or unoriginal. The poem entitled “*” begins in a more confessional mode:

yesterday I took off my clothes and thought of you

I avoid eye contact with everyone in public spaces

you can act a certain way

I’ll respond in a fairly predictable way…

lately I feel like everything is stupid

every day I would write the same poem

The poem goes on to list the variety of activities that seem to be attempts to jar the speaker out of this state of ennui, and, you guessed it, they go like this: “I click on gmail/ I click on word documents/ I click on firefox/ I click on myspace/ I click on my blog/ I click on statcounter” and so on. This pattern repeats for several pages with occasional statements about what the speaker is anxious about, at which point the poem then breaks into a two page repetition of a single line, “there is nothing in my reality that I feel I want enough to try.” Obviously, all that clicking isn’t helping.

Although both writers wrestle with the dichotomy of belonging and alienation, Calvocoressi’s narrators look for solace through collective actions such as church and sports, while Gorrell’s search for acceptance leads to attempts at connecting online that only increase his separation. These two writers inhabit the same cultural moment but their style, tone and subject matter couldn’t be more divergent. Somehow there’s satisfaction in reading these two polar opposites in how they demonstrate the vast scale and range of contemporary American poetry; it serves as a reminder that we all miss out when we limit ourselves to our own side of the fence.

Related Articles from The Fanzine archives:

Rob Tennant’s review of Kaya Oakes’ Slanted and Enchanted

Thom Donovan profiles Philly’s Avant-Garde Poetics

Review of Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary

Also: image on 4th page is of Brandon Scott Gorrell.