We Are Not Here: An Interview with Aaron Mirkin

24.03.15

We Are Not Here is the 2013 short film debut of director Aaron Mirkin, who also wrote the screenplay based on the story “The Relationship” by Lonely Christopher from his collection, The Mechanics of Homosexual Intercourse. It premiered at the Toronto International Short Film Festival, where it won Best Experimental Film. It has also shown at festivals and screenings elsewhere in Montreal and Toronto, Canada; Regensburg, Germany; Clermont-Ferrand and Cannes, France; and San Sebastian, Spain.

Author Samuel R. Delany has said of the film that it “is amazing, moving, and brilliantly economical. Before it’s finished it explodes in the head and keeps on exploding for hours, days afterward.” Filmmaker Guy Maddin called it “gorgeous and haunting [with] a great tone, wonderful frames and performances. Beautifully written too!” It was made available online as part of programming by the Canadian National Screen Institute and can be viewed [here]. Lonely Christopher and Aaron Mirkin recently corresponded by email about their experiences creating the story and the film.

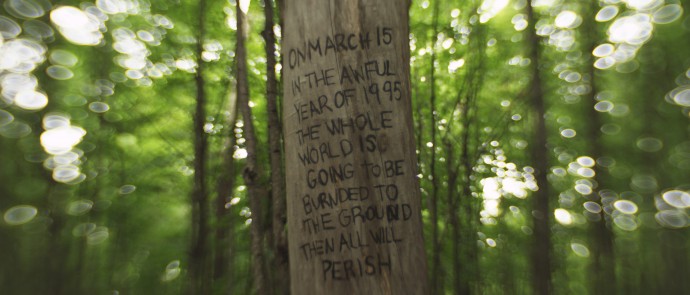

Lonely Christopher: “The Relationship” was conceived of as a formal exercise, to write a story as a triptych of individual scenes—the narrative coming from what could be made of the relationship among them. The thing about the shed, the lake, the forest, that was to function as a sort of interstitial binding for the three different scenarios, buttressed by a prelude and coda about the road. I wanted to explore what could be done with ambiguity. What is there, for the reader, comes from what’s not there. I think about it now in terms of creating textures. The substance of it is textural. The elements that are made available, being the interactions between characters and the descriptions of objects and nature, relate to each other and suggest an overarching concept but are inconclusive. Regarding the road—what it means and whether it will even arrive—the point is the mystery.

Aaron Mirkin: You mention the road scenes being a prelude and coda, so I’ll bring up the fact that I believe we’ve discussed the structure in relation to musical form, at least I know I have. Though it is not as specific a form as a sonata, fugue, or cannon, I do believe the structure of the story is comparable to that of some classical music. With the road sections acting as prelude and coda, the scenes with characters acting as individual movements with a recurring theme, and the shed/lake/forest as interludes. The idea of utilizing musical structures within filmmaking is something that has interested me for some time, so the structure of “The Relationship” was definitely one of my main interests in adapting it into a film. Multiple stories within a film are not uncommon, but they usually have very clear connections between the stories or characters. The ambiguity of the relationship between the scenes added to my interest in adapting it into a film.

After the film was completed I wondered how this ambiguity had been affected in the adaptation. “The Relationship” is told from the perspective of an omniscient narrator; he exists within We Are Not Here but only within the scenes without characters. This creates two very distinct types of scenes within the film. The narrated scenes are treated differently in terms of visuals and sound than those with characters: there is music, they cut faster, they use more elaborate camera moves, and a different kind of lens. While the character scenes are covered fairly traditionally and contain no score. I think that having these different styles of scene affects the ambiguity of the relationship between each scene, but I’m not entirely sure if it enhances the ambiguity, reduces it, or maybe creates a different ambiguity.

LC: The way the piece is sequenced does borrow more from musical composition or even painting (in terms of it possibly functioning as a polyptych) than conventional storytelling or narrative drama—that’s why it was exciting when you contacted me about adapting it specifically, because, out of everything in the collection, The Mechanics of Homosexual Intercourse, “The Relationship” is definitely one of the least cinematic stories.

I didn’t know who you were, you were in film school at the time, there wasn’t much you could show me in terms of previous work—but especially since you chose one of the more challenging stories in the book, one that didn’t seem to lend itself to adaptation in a straightforward way (or at least in a way that would yield a straightforward result), I was very intrigued. And it turned out that you’re an intelligent and skilled filmmaker who knew what you wanted to achieve, so it was a success. I quickly learned that you knew what you were doing, so it turned out to be a matter of handing everything over to you and waiting to see what happened. You wrote the screenplay, which is very true to the source material. The first draft was more or less a transcription of the story, edited down for length—although in post-production I know you added a couple of important lines of dialogue to polish the ending. We did have many conversations about the project, but they were mostly about you explaining your intentions and keeping me abreast of how things were going.

Another of the stories, “Milk,” was adapted into the short film Petit Lait in France a little after We Are Not Here and now there’s a project in the works in Brazil to adapt the title story of the collection—in those cases, I gave or am giving slightly more input, mostly around issues of cultural translation and my authorial perspectives, but in your case you told me you were struck by the “atmosphere and intellectual ideas” of the story, and you already had what you wanted to do explicitly mapped out, so you didn’t need much from me because your grasp on the material was firm.

Can you discuss the circumstances surrounding the production of this film? I know you heard of The Mechanics of Homosexual Intercourse by way of Dennis Cooper, who selected it for publication—I remember at first, and this was back in 2011, you were planning to make this short as your senior thesis in school. But something happened with that? I don’t remember, I feel like there might have been some controversy about the violent subject matter, and in the end you weren’t allowed to do it. But you told me you were going to make it happen anyway and you produced it independently after you graduated.

AM: Despite the story not being the most obviously cinematic, I found the text to be incredibly evocative. From the first time I read it, I had images in my head and ideas of how to put them on the screen, though some of the images changed in the final product; I think it’s a testament to the power of the prose. It didn’t take me long to decide that I wanted to adapt it for my thesis project at Ryerson University. When I did contact you, you were very easy to deal with, and I very much appreciate that. The fact that you were so open to the idea and that after I showed you the first draft you basically left me to my own devices, really gave me confidence. The confidence remained, despite all that followed at school.

After a few months of farcical script development meetings with one professor, who did not remotely understand the ideas for the film, I was told I would not be allowed to make it. Despite asking multiple professors, multiple times, it was never really explained to me why I wasn’t allowed to make the film. Despite all this, I was still committed to We Are Not Here, and we ended up shooting it in the summer. Making it out of school ended up being a blessing in disguise, though the film ended up costing more than it would have as a student film, we ended up with higher caliber actors than we would have otherwise. It also allowed the crew and I to be more focused and spend more time on the film.

LC: It helped that in Canada you have access to more resources—the arts funding for this sort of thing seems more reliable and plentiful than in the US. And since you work in Toronto, you have access to a lot of talent, especially when it comes to actors. You found a great mix of veteran character actors and ambitious kids to populate the film. Ron Lea, in the role of the Policeman, had a take on his character that was different than the way it plays on the page but which definitely worked. I wrote the Policeman as being far more manic, more bombastic—sort of a caricatured embodiment of the rage of power—and Ron went a more restrained, quietly unnerving direction. His victim, Grover, is played by SCTV and SNL alum Tony Rosato who unfortunately suffers from Capgrass delusion and has had traumatic real life complications related to believing that his wife and daughter were abducted and replaced by lookalike imposters, which is spookily resonant with the dilemma of his character, whose wife has become the apparent hostage of a malevolent force for unknown reasons.

Delusional misidentification syndrome also plays a role in the concluding vignette, with Monday, played by the amazing Julian Richings, believing he has found his lost son, played by Myles Erlick, despite the boy arguing that he isn’t a child at all but rather a full grown, 33-year-old man. That scenario manifests more ambiguously in textual form because, despite the narration describing the character as a boy and Monday physically handling him as somebody child-sized, there’s still more immediate room for confusion and doubt because the reader isn’t being presented an image—just conflicting written and spoken statements. With actors, you have to decide, do you cast an adult or a child? Then it functions differently, although either way the premise is creepy and ridiculous.

Sam Earle and Aidan Greene were great as the homicidal boyfriends Hamlet and Francis in the middle section. Aidan’s performance especially captured the character as written—he’s the archetypical demure twink. I think with Sam you must have directed him toward being more of the aggressor, the dominant personality between the two, which makes sense to amplify the psychodynamics of their relationship. In my version, they were pitched more on the same frequency. The choice of voice actor David Fox as the narrator was important because of the difference in how narration functions between fiction and drama. In “The Relationship,” the narration is mostly so omniscient that I don’t think the reader registers it as a character—what is happening is just being stated. The equivalent of that in film is to just show the action, as you did in the scenes where there are two characters talking to each other. But when there is a scene that is just descriptive language about a lake, it becomes much harder to relate what you need to by solely using visuals. Things become more complicated because there are actually three kinds of narration in “The Relationship.” The opening and closing passages about the road are in the form of a chorus, as if the whole town is speaking about its desire for and uncertainty about the road. Your approach in the film sort of unified everything while framing it in a different way.

AM: It’s true that Canada does have a pretty good public granting system for the arts, though there was no public money put into We Are Not Here. I wasn’t experienced enough at that point to apply for any grants, so it was self-financed and took a lot of favours. We really lucked out with the cast. It was my first time directing actors of such ability and experience, so I learned a lot. It was interesting to see all of their different processes; Ron Lea for instance, gave a variety of different performances for the scene. There were some takes where he was probably closer to what you had in your head, in the edit we settled on the colder and more reserved takes. The dynamic it created with Tony’s very inward performance made the scene, as you said, unnerving.

As for the Boy, I don’t think I ever considered having him be played by a grown man. I thought about doing something where in reflections we could see him as a man, but I thought it was more interesting if there wasn’t anything saying that we are seeing him from Monday’s point of view. There’s that ambiguity again. I was really impressed with Myles’ performance, his dialog was hard, he is speaking like an adult, and I think that Myles captured that. I think he was 14 at the time, so I want to give him kudos. He and Julian had a great dynamic, and I love Julian both as a performer and as a person.

The decision to make Hamlet the dominant character in the section came from the adaptation process. Once I cut down that scene from the original draft, Hamlet stood out as the character driving the scene: he’s the one asking the questions, he’s the one who initiates the kissing, and the one that brings up their plans to kill. I was a bit worried about these scenes going in, since Aidan was the least experienced actor and Sam was a mainstay on Degrassi, which requires a very different kind of acting, but both actors required little direction once we got going, and did a tremendous job. In fact, my favourite part in the film is the look they share after they find the dead dog, before turning around and continuing their conversation. There is so much said in Sam’s eyes in that moment. From early on I wanted David Tibet from the band Current 93 to narrate; I could hear his voice in my head when I read your words. The deal we had with the actor’s union prevented us from using anyone who wasn’t a member, so once I started thinking about local people, David Fox came to mind. His voice is so incredible and he’s a great performer. I asked both Julian Richings and another actor friend, William Ellis, if they had ideas about who would be good, and independently they both suggested David, and no one else. So that sealed the deal, and I asked him.

LC: Not paying me anything probably helped keep the budget down. But I understand that making films on this level doesn’t equate to profit. Although, after several (shall we say) “learning experiences,” I no longer license my writing, or do film work, for free. I actually wrote and directed a feature film, titled MOM, a few years ago—featuring Mink Stole, Michael Potts, Paul Lazar, and Janet Hubert—which was an utter disaster, in terms of the production, and which hasn’t really seen the light of day yet, is in fact barely finished even now, and for which I was never properly remunerated. These sort of things are considered “no budget” or “micro budget” productions—but for me, a starving artist, the amount of money that has to go into even the most austerely budgeted film project is mind reeling.

And that’s even with most of the people involved volunteering their time or never really getting paid well or correctly. Nobody is begging for this stuff to get made, or throwing money at it (especially in the US), but I’m glad it does happen because it’s necessary. There’s really no other choice than to try and make it work, for those of us who feel like they have to do it—but I’m content to be more on the writing side of things, because it’s cheaper. It doesn’t cost me as much to sit in a room and type something out as it does to realize it on film, or whatever the case may be. I will say, it’s always a large pleasure to watch my writing dramatized. To hear my words coming out of the mouths of others, I really like it and feel very lucky about it.

I feel like you and I make a good team, we have similar interests and perspectives and work well together, and we’ve been able to attempt other things since We Are Not Here. There was that script I wrote for you that was sort of inspired by the life and work of the American painter Thomas Eakins, with a sharp BDSM current running through it—that was the absolute last thing I did gratis, because I expected that I was working on spec, with the understanding that the money would materialize later, but then the funding never came through, and the whole thing collapsed, and you were sort of like, “Okay, that didn’t work out. What do we do next?” That’s one thing I don’t like about indie filmmaking—a lot of the time the work, the writing, goes unseen, if the money doesn’t come together. Nobody really cares about an unproduced script; it just goes in a dark drawer somewhere and is forgotten about. That bothers me. I put a lot of effort into that script, and was homeless and scrounging for food while I wrote it, and then nothing ever happened.

It’s great, and maybe against the odds, that We Are Not Here actually happened! And it’s easy for these things, especially short films, to more or less disappear even if they’re finished, so for We Are Not Here to have enjoyed a little exposure on the international festival circuit, and to eventually be available online—that’s good enough for now. Anyway, I know the score. You have to deal with this too. We try to help each other, and do our work, and get it out there. You directed a great music video for Xiu Xiu’s album Angel Guts: Red Classroom and it was probably just for the opportunity to collaborate with a genius like Jamie Stewart, and to have the experience. The only thing we’ve actually finished since We Are Not Here is a little book trailer for my poetry collection Death & Disaster Series, which was more or less you doing me a favor.

But pretty soon, lord willing and the creek don’t rise, you’ll be directing the short film Crazy House, based on a script that I wrote for you about “gay teen suicide.” It’s been a much more interactive collaboration because you came to me with a premise, an outline, and I changed it around and turned it into a different thing that still addresses what you wanted to get at to begin with, and we were in constant contact throughout the process, bouncing ideas off each other, and there’s a distinct sense of parity and synthesis to the process. And we’ll keep working together in the future and maybe one day get a feature off the ground.

AM: The cost of making films even on a microbudget level can be mindboggling. They usually make sense when you break them down, but when you see that big number, it’s hard to not think about how it’s significantly more than you’re going to earn this year. It was definitely a shame that the Thomas Eakins inspired script didn’t work out, I still think about it, particularly the structural elements. I realize now that it was a mistake to submit it for funding before We Are Not Here had finished its festival run. That said, maybe someday it could be revived. The amount of effort that goes into un-produced films is an unfortunate reality of both independent and big-budget cinema. There’s so much work that goes into a film before the shoot, and if, for whatever reason, you don’t get to the shoot, it can really hurt. Luck, timing, and connections often play a big role in what gets made.

We are lucky that We Are Not Here got made and that Crazy House is getting the funding it needs to be made correctly. I don’t want to give luck too much credit though, there was and continues to be a lot of hard work going into these films; from you and me, but also from my co-producer Miriam Levin-Gold and all the crew. We Are Not Here wouldn’t have been the same without them and I’m happy that most of them will be working on Crazy House. I’m really excited about this new film; the script you wrote is excellent, everyone who has read it has been nothing but positive. I’m also very pleased that the awesome Connor Jessup (Falling Skies, Blackbird, Closet Monster) has agreed to play the lead and that Jamie Stewart, who you rightfully described as a genius, will be doing the music. I’ve been a big fan of Xiu Xiu since I was a teenager so getting to do a music video for their song “New Life Immigration” was really amazing.

For me, Crazy House is a film about impossible love, loving someone who can’t love you back. Having the object of love be dead was the strongest way I could think to represent that and the added guilt that goes along with suicide escalates the emotions. I feel that that your script does a better job exploring what I wanted to explore than my idea ever could have hoped to. As you said, we make a good team, and I’m very grateful for that. I know that one day, sooner than later, we will get a feature going and it’ll probably be pretty crazy.