Under The Skeleton Tree: On Nick Cave and Decay

24.10.16

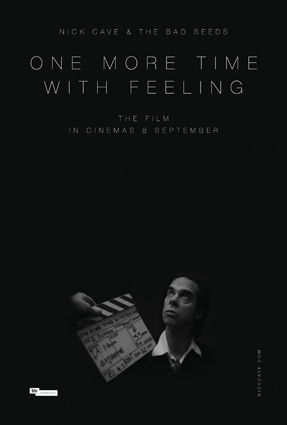

There’s a moment early in One More Time with Feeling where the director, Andrew Dominik, is talking to Nick Cave about narrative. They’re in the car, and though you can hear Dominik’s voice, the camera stays on Nick Cave, who is seatbelted, sipping coffee.

Cave is no longer interested in linear stories. That’s not how things really happen, he insists. Dominik cuts in, half joking, everyone’s story is basically the same. You’re born and you die. In the middle you deteriorate, decay. Cave nods in agreement, but his face crumbles. Dominick, though not intentionally, is thumbing an open wound. Decaying, Cave says, that’s what it feels like I’m doing.

One More Time with Feeling does its best work documenting how two families work around a central tragedy. The Caves are suffering from the inconsolable loss of their 15-year-old son, Arthur, and the Bad Seeds must play on around it.

One More Time with Feeling does its best work documenting how two families work around a central tragedy. The Caves are suffering from the inconsolable loss of their 15-year-old son, Arthur, and the Bad Seeds must play on around it.

The bulk of the film takes place in or en route to La Frette Studios in Paris while the Bad Seeds are recording Skeleton Tree. The hurry-up-and-wait nature of the recording process is intercut with staged performances.

Cave, of course, is the focus of the film, though the true star is his anguish. The man at the center of One More Time With Feeling is a very different Nick Cave than the one we saw in

Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard’s 2014 documentary, 20,000 Days on Earth. That wry, joyful Cave, a man who lived in a world of his own design and felt lucky to do so, is a distant memory, a mirage.

As a filmmaker, Domnick is much more sensitive than he is a conversationalist. The film is shot in stark black and white, as if the subjects are being haunted by the light. Tracking shots unspool, reveal their mechanisms, and return, spinning back into artifice. Cameras pause on blurry views, objects, cracks in doors, out open windows. There are voiceovers layered over performance, songs shimmying in through the cracks of silent moments and mundane conversation. He lingers in open spaces, the minutiae, as if to force the audience to sit a minute longer with the weight of this family’s grief.

This distance is unsettling, and for the most part, works. There are moments, though, where the reach is too long, and heavy-handed effects, like zeroing into a singer’s heart and back, or zooming out to a view of the earth from space, pull the viewer too far from the subject.

The mechanism of art film as document is a helpful one. Including mistakes, and verite flourishes–like when Jim Sclavunos says, “Fuck continuity,” and Cave, smiling, answers, “Yeah, fuck continuity!”–interrupt the tension, the same way that Dominik and Warren Ellis do with jokes and camera malfunctions. The fucking around is an act of protection. The director is as invested in Cave’s survival as the Bad Seeds are, as the viewer is.

Cave says it best himself, in one of the film’s many voice overs, “You change from the known person to an unknown person.” Even defeated, Cave is magnetic.

A different person’s tragedy, or a different perspective on it, could have been a much different, much worse, much less necessary thing. Having someone so sarcastic at its center makes this study of grief feel more genuine. The album gets finished. The Cave family lives through it every day. There is no tidy ending. There are no easy parables.

It takes a long time, nearly to the end of the film, for Cave to even say his late son’s name. The circumstances of Arthur Cave’s death aren’t discussed, only the impact. The closest Dominick comes is to end the film on lingering shots of the cliffs in Brighton, England, where Arthur fell, light glimmering out over the water.

Cave uses the word “trauma” throughout the film as a shorthand for his son’s passing. He can barely bring himself to specificity. When he does, he’s achingly blunt, “People say, ‘oh, he lives in your heart.’ He’s in my heart, but he doesn’t live at all.”

It’s unfortunate that Cave’s latest album, Skeleton Tree, will be associated with such tragedy. It is less a record obsessed with death than anything the Bad Seeds put out in the 80s or 90s.

It’s unfortunate that Cave’s latest album, Skeleton Tree, will be associated with such tragedy. It is less a record obsessed with death than anything the Bad Seeds put out in the 80s or 90s.

The album was written before his son died, but Cave would rather not be the prophet of his own trauma. Skeleton Tree is a record that throbs with loss, Warren Ellis’s string arrangements swelling around sparse piano. Like its predecessor, Push The Sky Away, it eschews the guitar-driven storytelling of previous Bad Seeds albums, instead surrounding Cave’s weary baritone with eerie layers of sound.

It’s not surprising, considering his catalog, that the lyrics deal with death and loss (and sex). But people have long been fascinated with death and evil and misery. It doesn’t mean we welcome it. “Susie is more superstitious,” he says, in an interview during the film. But one of Cave’s greatest strengths as a songwriter and performer has always been his keen ability to tap into primeval human emotion, to whisper our fears and scream our violence and cry out our love.

The songs are meditations, not stories. Cave evokes feelings rather than describing them. He’s becoming more abstract with age.

In the film and on the album, Cave embodies a kind of pain that is as universal as it is unfathomable. “They told us our dreams would outlive us…but they lied,” he sings on “Distant Sky,” the penultimate track. “Nothing really matters anymore…no matter how hard I try,” he wails on “I Need You.” It’s this ability to embody such difficult, unspoken emotion that has made Cave so compelling for so long.

Later, there is scene in the recording studio, where Earl and Susie Cave come for a visit. In a few wordless moments, we get a wide picture of their bond, mother leading son, son guarding mother. Cave lights up when he sees them, jokes about Susie’s fur coat, Earl’s new hair color. He pulls his son in for a kiss on the cheek, and hugs him long and hard. Susie wraps as much of herself as she can around both of them. It’s an important moment as the camera lingers on them, the living.