Undead Poets Society: A Review of Kim Yideum’s Cheer Up, Femme Fatale

24.05.16

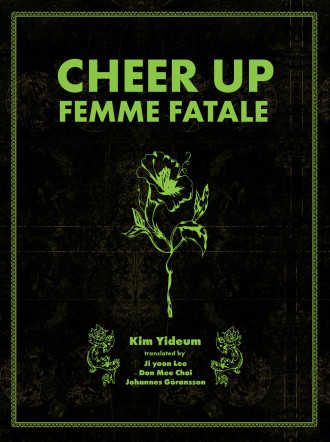

Cheer Up, Femme Fatale

Cheer Up, Femme Fatale

by Kim Yideum, trans. by Ji Yoon Lee, Don Mee Choi, and Johannes Göransson

Action Books

80 pp / $16

Last year, Johannes Göransson and Mia You engaged in a far-reaching conversation about translation. Initially provoked by You’s review of Kim Hyesoon’s Sorrowtoothpaste Mirrorcream (translated by Don Mee Choi) in Bookforum, the conversation revolved around the question of context: How do we understand a work taken out of its original linguistic and cultural context and transferred into a new one via translation? While the question begets other questions—about translation, about reading, about reviews—the key takeaway is both writers’ insistence that there is no “proper” context for a book in translation—or for any book at all.

While in many ways Kim Yideum’s Cheer Up Femme Fatale is out of my context as a monolingual white American reader with minimal knowledge of Korean history and literature, it also isn’t, as Kim writes into/out of a crosscultural grotesque tradition that I share. But her work also exceeds that tradition (which is really many traditions). Kim is well known in Korean poetry and internationally, and Cheer Up, Femme Fatale is the first collection of her poems published in English. Translated by Action Books dream team Ji yoon Lee, Don Mee Choi, and Johannes Göransson, it brings together a selection of poems from three of Yideum’s books—A Stain in the Shape of a Star (2005); Cheer Up, Femme Fatale (2007); and The Unspeakable Lover (2011).

It’s a witchy, traumatized book. At turns flippant, mordant, grieving, confrontational, Kim’s poems swing wildly, and the punches that land are both comedic, and hurt. Many are populated by grotesque objects; many operate in a Gurlesque mode. Especially in the first two sections, Kim’s poems are delivered by an unstable, polyvocal “I”, an incoherent subjectivity we might call, via the title, the femme fatale. Kim’s femme fatale is dangerously charming, languid, shockingly morbid. Her smile is a leer; her wink a nervous tic; she will not cheer up.

Her occasional power is displayed in outlandish ways. In “Fluxfilm No. 4 (Lesbian),” a woman walks across a bridge and the objects around her break and repel: “When I approach, mirrors crack and coats rip. Beds fall apart, and bookcases topple….When I approach, things run away.” Elsewhere, other things—objects—become animated and agentive. “Lost and Found” presents a cabinet of not curiosities but “wretched objects” that “fornicate and reproduce” while abandoned to storage. Discarded and sometimes paradoxical—e.g., “the gunshot sound of Mayakovsky’s suicide”—these lost objects will not rest.

Objects exert agency frequently in this book, which blurs human-object boundaries. In “A Sealed Woman,” our femme fatale enters a motel room to fuck; then, through a series of wild, generative leaps in image, becomes a mannequin who is swallowed by, becomes part of, a whale/lover on a waterbed that is “the billowing sea.” “The Guitarist on the Street” adopts similar logic, using substitution to transfer the visual properties of a baby onto a guitar: “The woman on the street holds a guitar tightly, as if to shove her breast into it.” Again, these discarded subjects-made-objects refuse to accept their lot. At the end of the poem, the guitar pushes her mother into the guitar case. Bye.

Other poems express an insistent boredom, yawning pointedly in response to everyday horrors. In “Avoidance Addiction,” eyeballs are “rolling on the ground, glistening like sewer rats”; a child “flushes down another child”; and “I can’t help but yawn.” The poem’s horror is made banal by the speaker’s flippant attitude, to potent effect.

The final section, poems from The Unspeakable Lover, articulates anxiety about poetry as an institution. Whereas the first section relishes in the generative power of poetic imagination, the poems in this third act seem resigned to, if amused by, its limitations: “Silently and swiftly,” Kim writes in the unusually lighthearted “Undead Poets Society,” “poetry makes nothing happen.”

This fatalism extends to the world at large. The sarcastic “Don’t Be Alarmed” offers a darkly pessimistic worldview:

While I sleep, levees collapse,

a submarine explodes.

Children kill their parents,

teachers kill their students.

But the political depression engenders wonderful surprises. Cheer up, she assures us: “If I die I’ll probably turn into a water bottle.” Many of these poems are devastatingly funny—a comedy that is morbid, perverse, searing, and all the more powerful for when the bubbles of mirth pop to expose a grim reality.

—————–

Megan Milks is the author of Kill Marguerite and Other Stories, winner of the 2015 Devil’s Kitchen Reading Award in Fiction and a Lambda Literary Award finalist; as well as three chapbooks, including The Feels, forthcoming from Black Warrior Review.