Titles Are a Kind of Vanity: An Interview with Ed Skoog

20.05.14

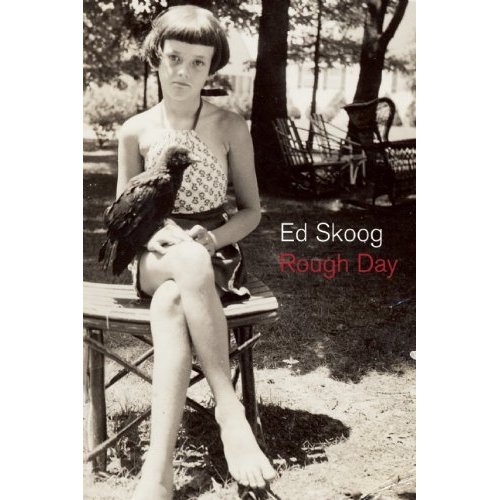

Ed Skoog is one of the most talented, sagacious poets working today. Seattle claims him as its own, but he’s lived in Kansas, Washington, D.C., New Orleans, Montana, and California. That migratory spirit informs his latest book, Rough Day (Copper Canyon Press, 2013). Fanzine talked with Skoog over the phone about Rough Day, the urge to migrate, and the vanity of titles. Below is the transcript.

FANZINE: Tell me a little bit about migration and the urge to travel –what you identified as zugunruhe in Rough Day. How do you think you use this as a concept in Rough Day – is it theme, content, style? More than [Skoog’s first book] Mister Skylight, there are a lot of rapid jumps, associative jumps, imagistic jumps…

ED SKOOG: Migration and restlessness have different forms. One is just being one who moves around a lot, which is my experience and seems to be the general experience of most people I know. Not to be regional, but to be sort of migratory for, mostly, economic reasons. Going where the jobs are. Coming from one place without much opportunity, going someplace where there’s more opportunity.

And then forced migration. That’s a bit of exaggeration. But, say, having to evacuate. That’s an experience that I’m familiar with. Having to move because of natural disasters. To relocate and re-vacuate. Returning home after you’ve been forced out. [Skoog lived in New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina; Mister Skylight touches on his evacuation and return to the city following the disaster]. And the ways that your relationships to place change. And then aside from their being outside forces that make us move around, which creates stories and which is a story of it’s own. Even without those forces, many of us—or at least me—would probably get up and go frequently. Like an old incontinent person (laughs). Curiosity, longing for adventure. Low threshold for boredom, which is probably the same thing.

So there’s also a migration of ideas. Aesthetic migration across time and across texts. Which I think refers to intellectual and emotional curiosity and turbulence I’m interested in observing in both my friends and in history and in myth and story. Those kinds of turbulences are very interesting to me. And then all of these things can be located in some aspect of poetic form, as well. So, the, restlessness are connected to the movement of the eye and the mind from the beginning to the end of a poem. From the beginning to the end of a book. Through line endings, line rhythms, line repetitions, repetitions of phrasing, grammar, that really help shape the form of the book—the poetic form itself is self-exiling.

FZ: Can you tell me a little bit more about this idea of the poem as self-exiling?

ES: Yeah – well, ‘self-exiling.’ Frederic Jameson in his approach to modernism and late capitalism observes and predicts that the artistic forms now tend to have a ‘flattening of affect,’ I think was his term. A leveling-out, and avoiding extremes of emotions –avoiding emotions altogether. And the forms tend toward the fragmentation instead of development. Pastiche, montage, instead of the more traditional forms of development. He’s not concerned whether that’s right or wrong, it’s just a critical observation, and I think it’s true.

A reader of Rough Day would probably say that it’s fragmented in form because of the lack of punctuation, and the way that the couplets and tercets revolve seems to be fragmented. But I’m really trying to find my way out of that trap, and I think the movement from one scene, one speaker, one image to another is not in my mind one of fragmentation, but one of moving on. Either being forced to move on by forces or moving on for—to use that term “self-exiling” reasons: moving on to avoid boredom, for adventure, or just trying to contend with what is now in front of one’s mind.

So I think that I like framing the speaker as being self-exiled rather than ‘fragmented,’ which seems to me increasingly like a computer term. Although that’s another aspect of it – the title for the book for a long time was “Cold Migration,” which is a term I remember from where you move one operating system or one database to another rapidly, without integration. Cold migration of data from one system to another. Which I think is terrifying. But also is one of the movement of data and of information. And the sort of corruption of that. The ways that instability and turbulence that I’m describing through migration and exile creates room for being co-opted or corrupted. There’s a vulnerability that comes with it, whether political, economic, sexual.

FZ: In Rough Day, you don’t have any titles (the first lines serve as the titles), and there’s almost no punctuation. I don’t know if this is the correct term, but you mentioned it once as an experimentation.

ES: I don’t see it as experimentation—it was a decision that I was confident in. Experiment in literature suggests a kind of “let me see if this works.” And I know that either does or doesn’t. I feel it is the natural and inevitable form of these poems and of this book. That arose from getting to know the work and working on it for years. if a sonnet sequence had been what seemed most appropriate, I would have happily followed that. Form is a series of decisions that feel right. I think there’s a lot of intellectual work that goes into it and critical understanding, and distance. But in the end, for me and for most people, it’s not a form unless it feels right. And by feeling right I mean it’s connected to the natural experience of—the final form of a poem should be connected to the inner logic of it. The outer logic of the poem should be connected to the inner logic. Outer logic being form, and the inner logic being in the essence or spirit of it. The inner logic of these poems spoke to me to get rid of things that were vanity.

And I think titles are a kind of vanity, or an advertisement for a poem that wasn’t appropriate to these experiences. And punctuation also—I wanted to write a better line than I had before. When we speak, we don’t use punctuation. We don’t say “period,” “comma,” “semicolon,” “dash.” I wanted to embody natural vocal patterns in the lines. And so I had to write lines that would sort of have those stage directions in them, or those emphases and de-emphasized things in the arrangement of words and in the line breaks. And that seemed to be connected to the spirit or essence of what I was trying to say. Rather than something I was opposing.

FZ: Tell me a little bit more about titles as advertisements.

ES: Bad titles are titles that aren’t really true to part of the poem are often advertisements. They’re often advertising that this is this kind of poem that does this. Or that they’re proper nouns, that indicate subject—‘Hey, you wanna read a poem about ice cream? Here’s a poem called “Ice Cream.”’

I’m averse to being sold things in the space of poetry. And a lot of titles seem like they’re trying to sell—not even sell the poem, but sell the personality, and that kind of turns me off. I think people—I read a lot of contemporary poetry, and I love it, but one thing that consistently disappoints me is the framing of it. The framing of a book, the framing of a poem. It seems like so many people are embarrassed to give much thought it, or to be thoughtful about. Maybe because it’s part of the appearance of the poem.

FZ: When I saw you read last, your poems seemed a lot looser. Sonically and narratively, they seemed a lot closer to Mister Skylight than Rough Day.

ES: So what I’m working on now – I believe it’s building on Rough Day and Mister Skylight, in the sense that I hope that I’m building a body of work. I’m writing now are longer poems that are more meandering that follow their formal concerns but there are fewer formal concerns.

To meander—the looseness is a kind of formal decision. To associate from idea to idea without a lot of pyrotechnics. I’m comfortable that at this point they seem to be essays with line breaks. Because they’re all sort of doing the same thing. And they’re all sort of surprising me.

FZ: So the inner logic of these new ones is dictating the conversational tone.

ES: They’re very conversational. And part of that comes out of – I’ve been doing this podcast for about a year with my friend John. And so we do that about once a week. And so talking to him, just having regular long conversation with friends, which may be—I may be more attuned and appreciative of it because I’ve been hanging out with a year-and-a-half year old child—has been nice. And I want to write poetry that contain those pleasures and freedoms of talking. But still have my concerns about composition. They’re still built to last, and are therefore artificial. The poem has to be very artificial. I recognize the artificiality of these… that ‘affected naturalness’ is a rigorous choice. But still having fun! I’m mostly writing about embarrassment. Things that are embarrassing to me to talk about, or are generally embarrassing for people, and that’s fun.

FZ: I’ve always felt that ‘fun’ or ‘delight’ get a pretty bad rap. It never seems to be something that people bring up because maybe it’s sort of, I don’t know, childish or superficial?

ES: I want it to be worth reading. This is the ancient—the poetic advice from antiquity, from Horace onward: ‘a poem should start in delight and end in wisdom.’ Because I’m kind of a simple-minded person, I’ll take delight. I like to see people juggle. I like jokes.

FZ: You told me maybe a couple years ago that “A poet should release a book every five years, preferably every ten.” Is that still true for you?

ES: (Laughs) That’s enough, isn’t it? I think—I’m not like a politician saying,“I’m not going to run for a third term.” But I think that… for the most part, poets that I like to read don’t seem to think super quickly. The books that I admire most tend to be the ones that have had a little gulf of time since the last one. Or to be someone’s first book who’s been writing for a long time. Because then there’s some principle of selection that’s happened. That people have thrown out some good work in favor of emphasizing something truly outstanding. That’s what I’m hoping to do with what I’m doing now.

FZ: Doesn’t that terrify you though?

ES: To me, the damage has already been done. (Laughs). If I die tomorrow, I probably won’t have any greater claim, or any less claim, to being a writer in 20 or 30 years, 50 years, then if I published five or six more books.

FZ: Here’s a question from our friend Rich Smith: “Why should we persist? Why should we go on?” I think he trying to think of it in terms of the sort of… does poetry give us the means or the motivation to continue and persist? Which I think is apt – in Rough Day there’s a lot of dire stuff. You have a line about extinction: “there was some noise and there was no noise”.

ES: We’re preparing a way to get accustomed to the horrible things that happen. Because we have to make room for the terrible things in our lives. Otherwise we will be unprepared for them when they happen to us. And I mean that as individuals, but I really mean it culturally. Even though I say I, there’s a communal effort to prepare and deal with disasters, horrible things, and more importantly the horrible things we do with the human tragedies, human-caused tragedies: holocausts, genocides, cruelty on small and large scale, and our impact on the rest of the lives on earth that we share space with, whose lives we are making difficult, painful, or nonexistent. One of our jobs as writers—one of the historic roles of the poet is to provide some commentary on these matters. Either in advance through prophecy, warning, or as witnesses. Just to describe what we’ve seen. And to help put things back together again. Rebuilding. We persist to help others persist, either through delight or wisdom – those Horace beginnings and ending. These are things we can discover in ourselves and provide to others. And that’s valuable. I’m skeptical of poetry’s claims to do these things because it doesn’t seem to stop anything from happening, and it doesn’t seem to help very many people. But I don’t think it does, but I still think that’s the impulse for it. There’s a lot of things we do that don’t make any sense, and poetry is one of them.

——————–

Ed Skoog is the author of two collections of poetry, Mister Skylight and Rough Day. Rough Day is available from Copper Canyon Press.