The Year the Western Returned?

19.01.08

Was 2007 really such a good year for the Western? Down at the Zeitgeist Corral, aka the November 11th issue of the New York Times Magazine, Daniel Day-Lewis gazes steely-eyed from the cover, above the headline (in modified Ponderosa font) “Hollywood Goes West.” Even a skeptic like the Village Voice’s J. Hoberman acknowledges the phenomenon, if only to dismiss it: “No matter what anyone says, the western is over; eight years of cowboy presidency notwithstanding, it will take a time machine to bring it back.” Hoberman means that the handful of 2007 films self-identifying as Westerns can’t embody the genre, only grapple with its implications as America’s preferred myth.

Was 2007 really such a good year for the Western? Down at the Zeitgeist Corral, aka the November 11th issue of the New York Times Magazine, Daniel Day-Lewis gazes steely-eyed from the cover, above the headline (in modified Ponderosa font) “Hollywood Goes West.” Even a skeptic like the Village Voice’s J. Hoberman acknowledges the phenomenon, if only to dismiss it: “No matter what anyone says, the western is over; eight years of cowboy presidency notwithstanding, it will take a time machine to bring it back.” Hoberman means that the handful of 2007 films self-identifying as Westerns can’t embody the genre, only grapple with its implications as America’s preferred myth.

So I’ll rephrase: Was 2007 really such a good year for the revisionist Western? That is, have we actually learned anything about the genre than we didn’t know this time last year, with the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Sam Peckinpah series and with Robert Altman Memorial screenings of McCabe & Mrs. Miller fresh in the minds of NYC cinephiles?

Renaissance hack James Mangold’s 3:10 to Yuma has some claim to “classical” status, being a remake of a ’57 original about family values and Christian steadfastness. (And also by dint of its curiously underreported dash of vintage racism: among the many shoot-‘em-up set pieces with which Mangold augments the original is a sneak attack from a night-stalking band of Apaches. They “like killin’”, we’re told, and we have to take that on faith since the Apaches are speechless, undifferentiated blurs of feathers and facepaint, and that’s all we have time to notice before Russell Crowe’s Ben Wade affirms his manhood by slaughtering them.) The premise is as old as the frontier: a man, farmer and homesteader Dan Evans (Van Heflin then, Christian Bale now) proves his mettle by protecting his family from the threat of violence and sexual violation (in the person of the outlaw Wade) and remaining pure against the other side’s Mephistophelean overtures.

This is the sort of trophy-polishing assessed in The Terror Dream: Fear and Fantasy in Post-9/11 America, Susan Faludi’s recent feminist survey of gender-coded American narratives of self-defense, both in their rather questionably sourced origins and their primary influence on this decade of dick-swinging American sociopolitics. But even conservative hetero-normalcy has its poets, and Delmer Daves’s understated handling of the original 3:10 to Yuma makes a steady case for the quiet strength of the classic American patriarch. Mangold, though, strong-arms us. Bale proves pretty handy with a piece, despite a bit of subtext––sorry, old war wound––hobbling his gait, and billboarding the contrast between his presumed physical inadequacy and Wade’s superphallic potency. As for screenwriters Michael Brandt and Derek Haas’s characterization of Wade, well, let’s let The New Yorker‘s David Denby decode it:

This is the sort of trophy-polishing assessed in The Terror Dream: Fear and Fantasy in Post-9/11 America, Susan Faludi’s recent feminist survey of gender-coded American narratives of self-defense, both in their rather questionably sourced origins and their primary influence on this decade of dick-swinging American sociopolitics. But even conservative hetero-normalcy has its poets, and Delmer Daves’s understated handling of the original 3:10 to Yuma makes a steady case for the quiet strength of the classic American patriarch. Mangold, though, strong-arms us. Bale proves pretty handy with a piece, despite a bit of subtext––sorry, old war wound––hobbling his gait, and billboarding the contrast between his presumed physical inadequacy and Wade’s superphallic potency. As for screenwriters Michael Brandt and Derek Haas’s characterization of Wade, well, let’s let The New Yorker‘s David Denby decode it:

“This cultivated gangster likes to observe other people; he draws pictures of anyone who interests him and quotes Biblical verse—he’s an aesthete and an ironist …”

Speaking of connect-the-dots, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford might have been somethin’ else, if director Andrew Dominik had let a real writer near his screenplay. The first thing he (a real writer) would have done would have been to scale back the backseat-driving voiceover, which doesn’t even let Bob Ford take a drink from the glass of water on the dresser without intoning, in a voice musty with nostalgia, that "Bob Ford took a drink from the glass of water on the dresser." Dominik’s onto a revisionist something with his conception of the Western icon James as brought down, in his own time, by his own myth––but he lets the groupie-speak of Casey Affleck’s Ford do too much of the talking, when Roger Deakins’s autumnal, pinhole camera-style cinematography is a far richer suggestion of a world already turning sepia.

Meanwhile, back at the Times Magazine, A.O. Scott points out that both Mangold and Dominik tip their Stetsons to the West’s original mythmakers:

Meanwhile, back at the Times Magazine, A.O. Scott points out that both Mangold and Dominik tip their Stetsons to the West’s original mythmakers:

In each, a young man is obsessed with the principal outlaw—Pitt’s Jesse James and Crowe’s Ben Wade—whose notoriety has made him the subject of dime novels and mass-produced engravings. The young admirer diligently collects these and pores over them with proto-fanboy zeal, fantasizing about growing up to be just like his idol.

… “3:10 to Yuma” and “The Assassination of Jesse James” are intensely self-conscious about the accumulated mythology of the Old West, which in their accounts began to accumulate even when the West was still old and wild. The folks who populate these stories, in other words, are to some extent aware of the significance, the legendary resonance of the stories they are living. They understand that they are living not just in the West but also in a western. And so the films become, in a way, elegies for themselves. Their sophistication manifests itself, curiously, in a will to become naïve, to restore a kind of direct, innocent perspective on the West that they half-admit was a fantasy all along.

It’s a good point. It’d be a better point if Scott, astute but resolutely nonconfrontational (he writes for the Times, after all) had gone on to say that Sergio Leone didn’t need these heterogeneous subplots to acknowledge How the (Idea of the) West Was Constructed — that that’s what every one of his gargoyle close-ups and Mediterranean backlots was about.

A genre of iconic faces (say, John Wayne) and sweeping vistas (say, Monument Valley), the Western has traditionally used elemental cinematic grammar—close-up and long shot—to relate the elemental American myth: the man in landscape. Leone distilled and enlarged these genre-film conventions into a historical archetype. His films aren’t about American history—especially not Once Upon a Time in America—but about the history of some gonzo movieland, where all narrative arcs are perfect parabolas.

A genre of iconic faces (say, John Wayne) and sweeping vistas (say, Monument Valley), the Western has traditionally used elemental cinematic grammar—close-up and long shot—to relate the elemental American myth: the man in landscape. Leone distilled and enlarged these genre-film conventions into a historical archetype. His films aren’t about American history—especially not Once Upon a Time in America—but about the history of some gonzo movieland, where all narrative arcs are perfect parabolas.

Summer Love, a “kielbasa Western” directed by the Polish artist Piotr Uklanski, screened this fall at the Whitney Museum, and has a conceptualist’s understanding of cinematic space as the language of mythology. The bare-bones stranger-in-town plot takes place in a supposed outpost consisting solely of bar/bordello, general store and sheriff’s office, populated by sweaty, drunken grotesques: supersized soundstage pulp, and nothing but. But Uklanski decides to deconstruct the Western by blowing raspberries at it, in the form of big-time viscerality, surpassing 2006’s The Proposition––with its festering bullet wounds and flogging of a dead man––for ick factor. And thematic inadequacy: that the Western documents America’s history of violence is a revelation only in a world that stopped turning midway through the opening credits of The Wild Bunch. Or before Ethan Edwards came in through that doorway. Or before the last Great Train Robber unloaded at the audience.

Not to take things too far afield, but the year’s true Leone heir was Johnnie To’s Hong Kong pistol opera Exiled: the H.K. action cinema, all slo-mo gun battles and expressionist squib packets, is like the spaghetti Western about myths writ in the language of film. And Exiled’s score sounds like a series of Morricone outtakes. Or maybe that’s not too far afield, not if the Western’s resurgence is on account of some new blood. The west Texas of Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men, and the Coen Brothers’ film adaptation, is staging ground for the eternal pioneer conflict between chaos and order — between Chigurh, who thinks a coin toss is as good a reason as any to end a life, and Sheriff Bell, who, like generations before him, wants to believe at least in the safety and sanctity of a home.

It’s an open question as to how aligned the reclusive McCarthy is with Bell––the religious doubt and hints of befuddled obsolescence in Bell’s narration gnaw at the book’s foundation, but it’s within that foundation that all the book’s action takes place. And McCarthy is comfortable with the tangible applications of this kind of Manichaeism, while the Coens are interested in it only as genre framework. A good ole boy lawman shakes his head over those “kids with green hair and bones in their noses,” and Tommy Lee Jones’s Bell nods––though in the novel, that’s Bell’s own line. Another thing the Coens don’t make Jones say:

It’s an open question as to how aligned the reclusive McCarthy is with Bell––the religious doubt and hints of befuddled obsolescence in Bell’s narration gnaw at the book’s foundation, but it’s within that foundation that all the book’s action takes place. And McCarthy is comfortable with the tangible applications of this kind of Manichaeism, while the Coens are interested in it only as genre framework. A good ole boy lawman shakes his head over those “kids with green hair and bones in their noses,” and Tommy Lee Jones’s Bell nods––though in the novel, that’s Bell’s own line. Another thing the Coens don’t make Jones say:

[She f]inally told me, said: I dont like the way this country is headed. I want my granddaughter to be able to have an abortion. And I said well mam I dont think you got any worries about the way the country is headed. The way I see it goin I dont have much doubt but what she’ll be able to have an abortion. I’m goin to say that not only will she be able to have an abortion she’ll be able to have you put to sleep.

Little things like that. But these deferrals maybe explain how the Coens—who’ve sent men who aren’t there, pregnant cops, and hippie detectives on end-runs around genre convention—passively accept a version of the West, and the Western, that’s little different from 3:10 to Yuma’s (though their process-oriented direction is a vast improvement). It’s all rugged landscape, welcoming domesticity, and the men who ride off into the former to preserve the women of the latter.

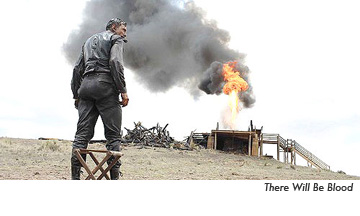

The year’s other best Western, according to Hoyle, is neo-, too. I should say right off that There Will Be Blood doesn’t quite work for me. P.T. Anderson seems to be constantly generating strategies of containing Daniel Day-Lewis, his gusher of a leading man. It’s all work and no dialogue for the first reel, and Anderson frames Day-Lewis throughout within iconic landscapes vast and historically resonant enough to tame him—only to have Day-Lewis sprint away with the movie during the home stretch, beginning with a baptism scene that plays to his most ecstatic tendencies, and that final outburst, staged in a room with the scenery at a chewable distance.

But Anderson needs Day-Lewis, and that seam-bursting tension, to get to the savagery with which the early oil baron Daniel Plainview tears up the Western soil, and the families living on top of it. There Will Be Blood is a Western by dint of geography, sure, but more importantly by intent. The point I’ve thus far been circling, like a cowpoke rounding up the herd, is that the Western is an origin myth, America’s answer to the question: Well, how did I get here?

But Anderson needs Day-Lewis, and that seam-bursting tension, to get to the savagery with which the early oil baron Daniel Plainview tears up the Western soil, and the families living on top of it. There Will Be Blood is a Western by dint of geography, sure, but more importantly by intent. The point I’ve thus far been circling, like a cowpoke rounding up the herd, is that the Western is an origin myth, America’s answer to the question: Well, how did I get here?

It’s the economy, stupid. Land grabs and gold rushes and oil strikes brought us out there; law and order was there to make sure that everybody could hold onto what was theirs (Ben Wade robbed stagecoaches). In the classical Hollywood Western—a genre whose rise to prominence more or less paralleled that of Russian Communism— commerce is a stabilizing factor.

In the revisionist Western, commerce isn’t what opened the West, it’s what closed it. In Peckinpah’s Ride the High Country, The Wild Bunch, and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, it’s banking, railroad, and ranching conglomerates, respectively, that horn in on the outlaw spirit—while in Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller the corporate villains crush the free will represented by McCabe and Miller’s attempt at free enterprise.

In There Will Be Blood, adapted from socialist Upton Sinclair’s epic novel Oil!, it’s the very entrepreneurial spirit that’s corrupt (and the holy spirit, too, that other American forefather, in the person of Paul Dano’s preacher Eli Sunday), opportunistic, antisocial (“I want no one else to succeed”) and finally murderous. There Will Be Blood opens in 1898, on a landscape bereft of any signs of human civilization; it ends in the same territory a third of a century later, in a mansion as modern as any of its day. Well, how did we get here? Not without blood on our hands.

Since six and a half years of “Wanted: Dead or Alive” have come up empty, says Hoberman, our Westerns are only vital if they question the standard origin myth; it’s the fault of the filmmakers, I suppose, that the questions are the same ones we’ve been asking for decades. But our self-styled “cowboy president” was an oilman before he was either. By following the money, There Will Be Blood becomes the only Western of the year to strike out to unclaimed territory.

Since six and a half years of “Wanted: Dead or Alive” have come up empty, says Hoberman, our Westerns are only vital if they question the standard origin myth; it’s the fault of the filmmakers, I suppose, that the questions are the same ones we’ve been asking for decades. But our self-styled “cowboy president” was an oilman before he was either. By following the money, There Will Be Blood becomes the only Western of the year to strike out to unclaimed territory.