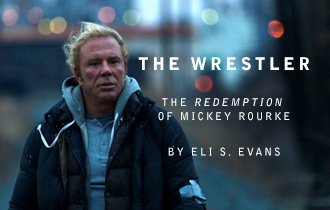

The Wrestler: The Redemption of Mickey Rourke

03.02.09

At a certain moment during Darren Aranofsky’s much-ballyhooed (but, in the end, not so much widely-distributed) The Wrestler, I discovered a tear rolling down my left cheek (the cheek, as luck would have it, that was facing away from my companion). It was a strange tear—one that seemed less a response to what I was watching than it did, like sweat to exercise, a mere byproduct of watching it—and yet there it was all the same, unmistakable in its identity: a tingle along the edge of my orbital bone, then a cool wetness cutting its gravity-driven path toward the jawbone. I did not wipe it away, at the time, for fear of being caught; now, having boldly acknowledged it in retrospect, I suppose the challenge is to somehow explain it away.

At a certain moment during Darren Aranofsky’s much-ballyhooed (but, in the end, not so much widely-distributed) The Wrestler, I discovered a tear rolling down my left cheek (the cheek, as luck would have it, that was facing away from my companion). It was a strange tear—one that seemed less a response to what I was watching than it did, like sweat to exercise, a mere byproduct of watching it—and yet there it was all the same, unmistakable in its identity: a tingle along the edge of my orbital bone, then a cool wetness cutting its gravity-driven path toward the jawbone. I did not wipe it away, at the time, for fear of being caught; now, having boldly acknowledged it in retrospect, I suppose the challenge is to somehow explain it away.

To a point—and perhaps this is what can make it difficult, at first blush, to account for its emotional ferocity—The Wrestler is pure formula. It is a story of redemption and resurrection, in the long tradition of stories of redemption and resurrection (see: Jesus1). A story, figuratively but also literally, about somebody coming back from the dead, and whether or not he will be able to find a new way of living. When we first meet one-time professional wrestling superstar Randy “the Ram” Robinson (Mickey Rourke), both his and his pseudo-sport’s best days are behind them. During the Eighties, when professional wrestling reached its zenith point, the Ram performed in front of sold-out arena crowds—and, we are led to imagine, drove fast cars, partied hard, and took his pick from a nightly litter of beautiful women in bellybutton shirts and jean shorts—but now, twenty years after the fact, he lives in a trailer park, tools around the tri-state area in a beat-up old conversion van, plays weekend shows before dozens of fans, rather than tens of thousands, supplements his meager wrestling income with hours working in the local grocery store’s stock room, and blows his rent money (within the film’s first ten minutes he finds himself locked out of his trailer for non-payment) on steroids and lap dances from an over-the-hill stripper by the name of Cassidy (Marisa Tomei). It’s a pretty miserable existence, all told—a reality whose wintertime harshness is reinforced by Aranofsky’s grainy images and unsteady, over-the-shoulder tracking shots—but a combination of sheer momentum and the slightly delusional dream of making it back to the top seems enough to keeps the Ram going.

1. Tomei’s character Cassidy references Mel Gibson’s The Passion of The Christ when she sees Randy come to her club bleeding from the temple after a match. Is it a dis or an homage to Gibson’s similarly blood, sweat and tear soaked bio? (And yes Gibson could perhaps use some lessons in redemption, or at least a salve for the old foot in mouth disease, from Rourke).

Before long, however, things take a turn for the worse. After a hardcore wrestling match that—told predominately in flashback—comprises the film’s most affecting visual sequence (staple guns, barbed wire, and a lot of vaguely expiatory blood), the Ram suffers a heart attack and is forced to retire from wrestling. Suddenly wayward, and suddenly poignantly aware of how absolutely, irrevocably alone he is, he seeks solace in Cassidy, who promptly deflects his emotional (more than sexual) advances by redirecting him to his family. Problem is, the only family he has is his daughter Stephanie (Evan Rachel Wood), a college student lesbian (with an angry, dreadlocked girlfriend) who bitterly hates him for having failed her as a father. Cassidy (real name: Pam) now reduced to the role of plot catalyst and thematic foil for the Ram, Stephanie becomes the story’s primary love object. And during a series of heartstring-tugging scenes that culminates with a walk through an abandoned amusement park the two often visited when she was a child (though she claims to have no memory of it), the Ram seems to be slowly but surely winning her back to his side. But when he oversleeps and shows up at her house two hours late for a dinner date, she throws him out and orders him never to come back.

Before long, however, things take a turn for the worse. After a hardcore wrestling match that—told predominately in flashback—comprises the film’s most affecting visual sequence (staple guns, barbed wire, and a lot of vaguely expiatory blood), the Ram suffers a heart attack and is forced to retire from wrestling. Suddenly wayward, and suddenly poignantly aware of how absolutely, irrevocably alone he is, he seeks solace in Cassidy, who promptly deflects his emotional (more than sexual) advances by redirecting him to his family. Problem is, the only family he has is his daughter Stephanie (Evan Rachel Wood), a college student lesbian (with an angry, dreadlocked girlfriend) who bitterly hates him for having failed her as a father. Cassidy (real name: Pam) now reduced to the role of plot catalyst and thematic foil for the Ram, Stephanie becomes the story’s primary love object. And during a series of heartstring-tugging scenes that culminates with a walk through an abandoned amusement park the two often visited when she was a child (though she claims to have no memory of it), the Ram seems to be slowly but surely winning her back to his side. But when he oversleeps and shows up at her house two hours late for a dinner date, she throws him out and orders him never to come back.

In your typical redemption story—be it love story, sports story, or, as is the case here, the two combined—the moment when all seems to be lost is always also the moment just before everything turns around. If The Wrestler had kept to its own formula, thus, it surely wouldn’t have been long before one final, decisive opportunity arose for the Ram to prove himself once and for all to his doubting daughter—an opportunity to show the genuineness of his love for her through sacrifice or definitive action—and then, when he did (and he would have, because he really does love her), the two of them would have reconciled and walked off arm in arm toward the setting sun, with now ex-stripper Cassidy alongside them just for good measure and the purposes of tidy closure. I do not want to eviscerate the ending completely, but suffice it to say that The Wrestler breaks from its own formula, in its devastating third act conceding neither redemption to the Ram nor closure to the viewer. Instead, both are left with nothing but the brutal realization whose imminence, I suspect, at every moment underpins The Wrestler’s unlikely emotional force: the realization, that is to say, that if you’ve managed to fuck your life up badly enough, you’re probably not going to get more than one shot at making it right; that if it seems like you’ve blown your last best chance, you probably have.

Of course, the Ram isn’t the only one looking for redemption in The Wrestler, as it turns out. There is also Mickey Rourke, the actor who portrays him, and whose story seems to run alongside his from even before the movie begins. Like Randy the Ram, Mickey Rourke was a momentary (and perhaps even more than momentary) superstar in the Eighties. Much as professional wrestlers exploit their (be they modest) acting skills in order to portray a certain kind of combat, Rourke exploited his history in combat—growing up in Miami he trained as a boxer, and was in fact slated for a shot at the welterweight title when a concussion drove him from the sport—to portray himself, in the tradition of Brando and Dean, as a particularly iconic kind of leading man: the kind who hides an artist’s tenderness and sensibility behind a rough and tumble exterior, but who at the same time really is as rough and tumble as he seems. Critics ate up his early work in movies such as Body Heat, Diner, and Rumblefish, but by the end of the 1980s things had taken a turn for the worse. Reputedly both eccentric and particular when it came to the roles he selected, Rourke turned down plush parts and appeared instead in at least one of the decade’s most infamous flops (Wild Orchids). On set, he was by turns abusive and unpredictable, and in time this reputation got the best of him. The list of important directors and actors unwilling to work with him grew cumbersome; the potential hazards of taking him on, for producers, seemed more trouble than they were worth. In 1991, his acting career on the ropes, he returned to boxing, and in fewer than three years fought eight times (six wins, two draws) and had his nose broken, according to his own estimates, four or five times. Then, of course, there was the alcohol and bar fights and allegations of domestic violence and drug abuse and before it was over Rourke had, like Randy the Ram, truly fucked everything up. “I lost my wife, my house, my career, my respectability,” he said during a recent CBS interview. And not unlike the Ram—thanks, it would seem, to some unfortunate combination of boxing and botched plastic surgery—Rourke also managed to get his face mangled along the way.

Perhaps it is because such a conclusion seems largely unavoidable, in light of the preceding, that nearly everyone who has so far written about Rourke’s undeniably powerful performance in The Wrestler has insisted that he was not really playing this character, Randy the Ram Robinson, so much as he was an only slightly off-center version of himself. And perhaps it is because a good bit of myth building is never bad for ticket sales that that nearly everyone with something to gain from the project has been doing his best to reinforce such an interpretation. During nearly two months on the interview circuit, Rourke has never seemed to tire of regurgitating the most sordid details of his own fall from Hollywood grace, nor ticking off his requisite references to second chances and long roads back. Director Aranofsky, for his part, has been weaving an almost too-good-to-be-true tale about having hired Rourke, then fired him and replaced him with Nicholas Cage when big money investors balked at throwing their resources behind some washed up actor from the Eighties, only to decide after too many sleepless nights haunted by the certainty that Rourke was the only one for the role that the big money investors could be damned, at last firing Cage and re-hiring Rourke once and for all. Even the studio has pitched in, featuring on its poster for The Wrestler—the one that hangs outside of theaters, making a last minute pitch to viewers dead set on seeing Paul Blart: Mall Cop—Newsweek’s David Ansen’s call to “witness the resurrection of Mickey Rourke,” as though the film were some sort of biopic of which Rourke were the subject, rather than a drama in which he delivers a performance worthy of the accolades it has received.

As strange as it may seem, however, I think it is the face—the same mangled and manhandled face (more joker’s face than Oscar rival Ledger’s, even in full makeup) that would seem to so clearly and easily belong to both at once—that ultimately turns back any effort to resolve Rourke and Robinson into mere identity. Here, I am thinking once more of that father-daughter scene in the abandoned amusement park. It is winter, when it takes place. Wind and bare trees and everything brown and dying in a way that is at once very sad and terribly familiar. Winter afternoon daylight dying over the ocean. Come to the end of the park grounds, or fairgrounds, the Ram and his daughter take a seat on a wall overlooking the water. For a couple of seconds we see them from a distance, framed by a sort of crumbling archway and silhouetted against sky and sea. Before long, however, the camera pulls in close on Randy’s face, and it holds its position there as he says, to this daughter of his who hates him but who now he desperately needs: “I’m an old, broken-down piece of meat, and I deserve to be alone. I just don’t want you to hate me.” Without question, this is The Wrestler’s signature line, replayed in ads and previews and uniformly rehashed by critics. But the funny thing is that when I think back on that moment in the film—remembering, now, that it was precisely this moment in which I became aware of that strange tear making its way down my left cheek—the words are not what come to mind (truth be told, I had to look them up online just to make sure I was getting them right). Rather, it is that scarred and swollen face. That wrecked face and the way that, as I watched, it seemed to suddenly cease to be the face of a movie character—Randy the Ram Robinson, washed up pro wrestler searching, having nearly died already, for a new and better way of living—and become, instead, the face of a person.

It would be easy, I think, to take this person (for what other person is there?) to be Rourke himself, and thus take his sudden irruption (as sudden as a tear) into the film as definitive proof that he and Randy the Ram Robinson really are one and the same: proof that, as just about everyone else seems convinced, Randy’s story really is Mickey’s story. But I don’t see things quite that way. As I see things, it is in fact precisely in this uncanny movement from character to person, precisely in this almost infra-thin shift from same to same in which is nonetheless held the most ineluctable of differences, that these two men, and their two stories, definitively part ways. For while the wrestler, in The Wrestler, gets one last best shot at redemption and blows it, the actor, offered the very same chance, seizes upon it with all the force of his being.

Stills from Fox Searchlight and Niko Tavernese