The Pugilist at Rest: Norman Mailer (1923-2007)

13.11.07

Then Norman Mailer. Overwhelming. I’d never seen Norman Mailer off the screen before. Guy’s eighty now, both knees shot, walks with two canes, can’t take a stride of more than six inches alone, but he refuses help going up to the pulpit, won’t even use one of the canes. Climbs this tall pulpit all by himself. Everybody pulling for him step by step. The conquistador is here and the high drama begins. The Twilight of the Gods. He surveys the assemblage. Looks down the length of the nave and out to Amsterdam Avenue and across the U.S. to the Pacific. Reminds me of Father Maple in Moby-Dick. I expected him to begin “Shipmates!” and preach upon the lesson Jonah teaches.

Then Norman Mailer. Overwhelming. I’d never seen Norman Mailer off the screen before. Guy’s eighty now, both knees shot, walks with two canes, can’t take a stride of more than six inches alone, but he refuses help going up to the pulpit, won’t even use one of the canes. Climbs this tall pulpit all by himself. Everybody pulling for him step by step. The conquistador is here and the high drama begins. The Twilight of the Gods. He surveys the assemblage. Looks down the length of the nave and out to Amsterdam Avenue and across the U.S. to the Pacific. Reminds me of Father Maple in Moby-Dick. I expected him to begin “Shipmates!” and preach upon the lesson Jonah teaches.

—From Exit Ghost, by Philip Roth

How lucky to have had Norman Mailer as our big writer—our genius and our jester—for this American half-century or more! Let us sing of the man’s ambition: that wild, prodigious, uneven, infuriating, embarrassing, brave and blustery and bruising arc, the longest, greatest song of himself in American letters.

Norman Kingsley Mailer: perhaps the highest praise one can lavish upon him is that it is inconceivable that another like him could rise from our midst. If he (or she!) did, there’d be no one at the literary banquet to greet him. What would today’s media know what to do with Mailer? A writer with the audacity to suggest he could change the course of public thought, that he could infuse some marrow into the country’s creaky bones, that a man of letters could exist at the cyclonic center of the American carnival? Not in the world of pixels and blips and small personalities Mailer lived long enough to see.

Nearly fifty years ago, in Advertisements For Myself (1959)—arguably the keel, the polestar of the bibliography, the volume in which the author created the persona that would sustain him over the next half century—Mailer laid out the career-long project for himself:

I find arrogance in much of my mood. It cannot be helped. The sour truth is that I am imprisoned with the perception which will settle for nothing less than making a revolution in the consciousness of our time. I could be wrong, and if I am, then I’m the fool who will pay the bill, but I think we can all agree it would cheat this collection of its true intent to present myself as more modest than I am.

For many a young writer, the liberating effect of sentences like those cannot be overstated. The notion that one could take on not just the republic of letters, but the Republic writ large, that the entire American crazy quilt could be one’s canvas, was heady, intoxicating stuff. Equally thrilling, the notion that writing wasn’t (only) an effete, sedentary endeavor, but back work—rough-and-tumble turbulent, physical, dangerous—the psychic equivalent of a boxing match, all of this, wrapped in the physical package of a wiry-haired pit bull of a Harvard-educated Brooklyn Jew; is it any wonder that, for many of us, Mailer was our Joe DiMaggio?

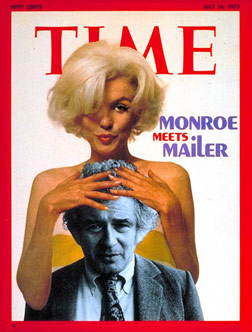

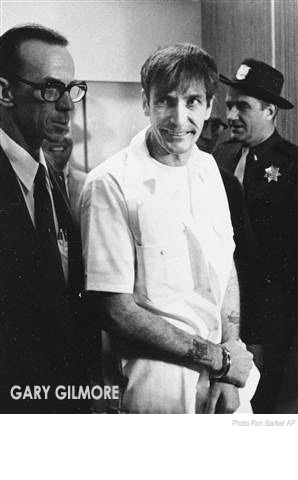

Mailer was synonymous with ambition. Here was a writer whose scope stretched as long as the horizon, a capacious self-creation that wanted to take it all on: World War II and McCarthyism, Kennedy, Castro, Oswald, and Nixon, Vietnam and Hollywood, Picasso and the Pharaohs, the moon shot and the "Rumble in the Jungle," Gary Gilmore and Marilyn Monroe, Jesus and Yahweh.

Toward the end of Advertisements For Myself, Mailer famously promises to deliver the big book, the white whale, the great bitch: “The book will be fired to the fuse by the rumor that once I pointed to the farthest fence and said that within ten years I would try to hit the longest ball ever to go up into the accelerated hurricane of our American letters. For if I have one ambition above all others, it is to write a novel which Dostoevsky and Marx, Joyce and Freud; Stendhal, Tolstoy, Proust and Spengler; Faulkner, and even moldering Hemingway might come to read, for it would carry what they had to tell another part of the way.”

Did he succeed? In the final estimation, does the achievement absolve the misbehavior, do the books stack up to the claims Norman Mailer made for himself over fifty years of American public life?

Re-reading Advertisements For Myself, one appreciates that as much as Mailer is associated with his sixties and seventies non-fiction, his literary persona was truly founded on a bedrock of fifties anti-establishment disgust:

Probably, we will never be able to determine the psychic havoc of the concentration camps and the atom bomb upon the unconscious mind of almost everyone alive in these years. . . that we might be doomed to die as a cipher in some vast statistical operation in which our teeth would be counted, and our hair would be saved, but our death itself would be unknown, unhonored, and unremarked, a death which could not follow with dignity as a possible consequence to serious actions we had chosen, but rather by dues ex machina in a gas chamber or a radioactive city; and so if in the midst of civilization—that civilization founded upon the Faustian urge to dominate nature by mastering time, mastering the links of social cause and effect—in the middle of an economic civilization founded upon the confidence that time could indeed be subjected to our will, our psyche was subjected itself to the intolerable anxiety that death being causeless, life was causeless as well, and time deprived of cause and effect had come to a stop.

As close as the man ever came to a kind of spiritual autobiography, Advertisements For Myself serves as a boon for young writers. For if the worth of any writer is ultimately his or her style, the imprint of his or her own personal truth—if style ultimately trumps plot or character—Advertisements For Myself, as no other book I have ever encountered, lays bare how difficult an effort, what a Herculean undertaking it is, to arrive at one’s voice.

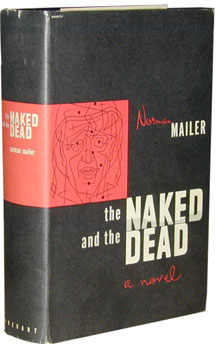

Here is Mailer, barely a dozen years into a career that began in the stratosphere as a twenty-five-year-old with the bestselling World War II novel, The Naked and the Dead (1948), on a shaky low ebb following the poor reception of Barbary Shore (1951) and The Deer Park (1955), trying on different hats, presenting his mediocre pieces and failed experiments, the drear work and false starts, like a Lower East Side street peddler laying out his wares on the sidewalk, and more, suggesting his strategy for the next thirty or forty years of public life: “[Hemingway knew] the value of his work, and he fought to make his personality enrich his books. . . An author’s personality can help or hurt the attention readers give to his books, and it is sometimes fatal to one’s talent not to have a public with a clear public recognition of one’s size. The way to save your work and reach more readers is to advertise yourself.”

Here is Mailer, co-founder of The Village Voice, announcing in his first column his intention “to be actively disliked each week.” Here is Mailer, in his brilliant and infamous essay, “The White Negro,” suggesting to the reader that the only bulwark against the conformity and suffocation of American life as most experience it is “the decision to encourage the psychopath in oneself, to explore that domain of experience where security is boredom and therefore sickness,” and his championing of the hipster as a philosophical psychopath, “a man interested not only in the dangerous imperatives of his psychopathy but in codifying, at least for himself, the suppositions on which his inner universe is constructed.” And, more disturbingly:

The psychopath murders—if he has the courage—out of the necessity to purge his violence, for if he cannot empty his hatred then he cannot love, his being is frozen with implacable self-hatred for his cowardice. (It can of course be suggested that it takes little courage for two strong eighteen-year-old hoodlums, let us say, to beat in the brains of a candy-store keeper, and indeed the act—even by the logic of the psychopath—is not likely to prove very therapeutic, for the victim is not an immediate equal. Still, courage of a sort is necessary, for one murders not only a weak fifty-year-old man but an institution as well, one violates private property, one enters into a new relation with the police and introduces a dangerous element into one’s own life. The hoodlum is therefore daring the unknown, and so no matter how brutal the act, it is not altogether cowardly.

There is volcanic rage in Advertisements For Myself, to be sure: the fury of self-love wrestling with self-disgust, an explosive voice marking the parameters of his talent, of an existential outlaw lighting out for the territories, of a talent willing itself into greatness, of a writer daring himself to forge an “art of the brave.” “The White Negro,” “The Man Who Studied Yoga,” “The Time of Her Time,” if these essays and short stories feel dangerous, still, fifty years later it is because in its embattled chronicle of fifties repression and revolt, Advertisements For Myself is a lit fuse of a book. Were more MFA candidates to read it, there would be fewer MFAs.

Unlike some contemporaries or near-contemporaries such as Philip Roth, Don DeLillo, and Thomas Pynchon, Mailer made the construction of a public persona, a performing self, a major component of his literary project. Here is a man who took out full-page ads in The New York Times to parade his own worst reviews as a fuck you to his critics; a man who published a photo of himself sporting a big black eye on the cover of Why Are We In Vietnam?; a man who ran for mayor of New York City on a platform including secession, the dividing of the city into districts dedicated to various pursuits such as pot smoking and free love, and the proposal of settling juvenile criminal cases with jousts in Central Park (he was surprised when he lost the election); a man who, with his Napoleonic confidence, suggested at every turn that he and he alone could offer a cancer cure for America’s schizophrenia.

“The devastating paradox of Mailer’s life and work,” wrote Martin Amis, who as a critic ran hot and cold on the author over several decades, “is that this pampered superbrat, this primal-scream specialist and tantrum expert, this brawler, loudmouth, and much-televised headline-grabber, suffers from a piercing sense of neglect.” What much of the hand-wringing on Mailer as a public figure misses is his heroism. From the outset he presented himself as big enough, expansive enough, to offer himself up as a punching bag and public ass. Forever in quest of a quarrel, it must have taken Mailer enormous courage to, in effect, spend the majority of his decades hollering: come on America, take your best shot! (Surely, for a certain generation of readers and thinkers, Mailer was as worthy a screen for the projection and absorption of fantasy as Dylan or Brando.)

Fortunately, then, Mailer found a literary strategy he employed like a safety valve. Borrowing a device from The Education of Henry Adams, beginning with the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Armies of the Night (1968), Mailer began casting himself in the third person as “Mailer”—braggart and boor, boozer and brawler—and the freedom, the liberation, he breathes from this literary distanciation is palpable on every page.

What was Mailer doing putting himself at the very center of the events he covered? And what did that uncanny literary strategy have to tell us about those tumultuous times? If Marshall McLuhan said that the medium is the message, here Mailer was telling us that the messenger was a big part of the message, too; that it was an impossible, dishonest cheat to feign objectivity. In the emerging media age of the sixties, the big shots didn’t simply make history, big personalities were history. Mailer covering the March on the Pentagon (which was, in itself, no watershed event of the era) wasn’t a journalist covering a story, he was, indelibly, part of that story.

And something more: if there was a kind of schizoid split between the book’s “Mailer,” the performing clown who enrages public audiences with a shambling, drunken, embarrassing Lyndon B. Johnson impression, and Mailer, the detached, lucid recording angel, that split dramatized something of the insanity of the period. If American life was getting crazier all the time, filtering it through the prism of a crazy, and crazy-making, personality like Mailer’s made better sense than not.

And something more: if there was a kind of schizoid split between the book’s “Mailer,” the performing clown who enrages public audiences with a shambling, drunken, embarrassing Lyndon B. Johnson impression, and Mailer, the detached, lucid recording angel, that split dramatized something of the insanity of the period. If American life was getting crazier all the time, filtering it through the prism of a crazy, and crazy-making, personality like Mailer’s made better sense than not.

The device offered other rewards. Third person reportage allowed Mailer to pump himself up and (preemptively) knock himself down in the same stroke, sometimes in the same sentence. In the pages of The Armies of the Night, Mailer can badger the poet Robert Lowell for telling him he thinks Mailer is the country’s best journalist rather than the best writer, making the claim for himself and mocking his pretensions at the same time. Mailer is often accused of being the least humorous of major novelists, but I think that misses the point. His most famous literary device is, by its very divided nature, hilariously self-deflating. Take this passage from Armies:

Mailer as an intellectual always had something of the usurper about him-something in his voice revealed that he likely knew less than he pretended. Watching himself talk on camera for this earlier documentary, he was not pleased with himself as a subject. For a warrior, presumptive general, ex-political candidate, embattled aging enfant terrible of the literary world, wise father of six children, radical intellectual, existential philosopher, hard-working author, champion of obscenity, husband of four battling sweet wives, amiable bar drinker, and much exaggerated street fighter, party giver, hostess insulter—he had on screen in this first documentary a fatal taint, a last remaining speck of the one personality he found absolutely insupportable—the nice Jewish boy from Brooklyn.

He would use the device of third person narrator again and again throughout the sixties and seventies, in a string of brilliant works of non-fiction journalism about political conventions (Miami and the Siege of Chicago, St. George and the Godfather), the moon landing (Of a Fire on the Moon), and the Ali-Foreman fight in Zaire (The Fight), among others, one of the longest, most triumphant runs in American letters. “I’d never come up with a story of my own that was as good as the things that were happening all through the sixties,” Mailer once said.

The easy classifications—fiction, non-fiction, autobiography—break down and congeal. As David Denby wrote, in a wonderful profile of Mailer that appeared in The New Yorker around the publication of his mammoth compilation, The Time of Our Time (1998): “One of the anthology’s more remarkable effects is to make us forget which realm we are in—nonfiction or fiction, reality or fantasy—or why any of these categories matter.” Mailer wrote: “I’d say the most surprising thing for me that emerged from working on the anthology was how little difference there is between my fiction and my nonfiction. When you have good nonfiction, you have fiction.”

The journalism fulfilled the requirement of every great author, the master accordion trick: reading Mailer, the world seems to expand and contract simultaneously, possibilities revealing themselves as one comes to understand more about how the world operates.

Mailer was misperceived as a chauvinist pig. In the pages of The New York Review of Books Gore Vidal once famously suggested a continuum existed between Henry Miller, Norman Mailer, and Charles Manson (“The Miller-Mailer-Manson man, or M3 for short, has been conditioned to think of women as, at best, breeders of sons, at worst, objects to be poked, humiliated, killed. . .”)—for which Mailer, also famously, treated Vidal to an epic head butting in the green room before taking the stage of The Dick Cavett Show.

One of Mailer’s great achievements, and one of his best, most supple and humorous uses of the third person device, is The Prisoner of Sex (1971), a wracked and worrying book about the feminist movement that, upon appearance, must have come across as the literary equivalent of Nixon opening China. Mailer puts himself on the rack here, as he does in Chris Hegedus’s and D.A. Pennebaker’s documentary film, Town Bloody Hall (1979), which chronicles a public Town Hall debate held in 1972 between Mailer and Germaine Greer, Diana Trilling, and other leading lights of the women’s liberation movement. (Reader, you haven’t lived—or, perhaps, have not lived fully—until you have seen Mailer in this film, as courtly as an English butler, pouring glasses of water for his co-panelists, or, better, fielding this question from audience member Susan Sontag, in full leonine flower: “In Advertisements For Myself you wrote that ‘A good novelist can do without everything but the remnant of his balls.’ Mr. Mailer, when you sit down to write, do you dip your balls in blue or black ink?”)

For all the madness of “The Time of Her Time” and the fervid hothouse novel An American Dream (1966)—in which our hero, Stephen Richard Rojack strangles his wife, sodomizes the German maid (“Verbotten!” she cries when Rojack “quits the sea to mine the earth”), then flings the dead wife’s body off the balcony, all in the book’s first fifty pages—the author was mislabeled a misogynist. If Mailer was considered reflexively anti-feminist, what he was in truth was anti-corporation (his catchall word for the apotheosis of conformity), anti-technology (insofar as contraception introduces pills and plastic into the procreative act), and anti-cant (e.g., the sloganeering that plagues both sides of the abortion debate).

Toward the end of The Prisoner of Sex, Mailer writes, in effect, that feminists have been fighting the wrong fight, that if a victory has been achieved, it is a Pyrrhic one; that what has been won is a version of the very oppression the man in the grey flannel suit should have dismantled in the 1950s:

Let her travel to the moon, write the great American novel, and allow her husband to send her off to work with her lunch pail and a cigar; she could kiss the cooze of forty-one Rockettes in Macy’s store window; she could legislate, incarcerate, and wear a uniform; she could die of every male disease, and years of burden was the first, for she might learn that women worked at onerous duties and men worked for egos which were worse than onerous and often insane. So women could have the right to die of men’s diseases, yes, and might try to live with men’s egos in their own skull case and he would cheer them on their way—would he? Yes, he thought that perhaps he may as well do what they desired if the anger of the centuries was having its say.

In the 1998 interview with David Denby, Mailer squared the deal this way: “You have to ask yourself, ‘Why was that revolution so successful?’ It worked for a very good reason. It was perfect for the corporation. . . You get on the shuttle from Boston to New York, and what do you see? You see a group of woman wearing tailored suits, carrying their laptop computers, and they look like female versions of the men, and they’re working for the corporation, and they’re proud of working for the corporation, and where in the old days men used to feel a small sense of shame—they really felt this was not the way to live, this was an empty life and it was destroying something in them that they couldn’t quite name—the women rush to it. They have become the gilt-edged peons of the corporation.”

The author was so flamboyant a self-creation that it may have detracted critical attention from the sensitivity of his style. For the long Mailer line, unreeled, as voluptuous as James or Faulkner, sentences that go on like arias, the reader finding himself holding his breath as the metaphors mount and the observations pile on; can the man sustain his observational momentum or will the next fillip topple the tower over into windiness or absurdity?

Much has been made of Mailer’s debt to Hemingway and Henry Miller, and his fifties writing as a pre-cursor to the Beats, but not enough attention has been given to Mailer’s line, for perhaps no American artist has been more attentive to the velocity, the weight and drip of line than Mailer. Reading Mailer’s journalism from the sixties and seventies, one is tempted to compare the author’s line with Jackson Pollock’s: both share the same control, the same speed and dynamism, the same belief in intuition and instinct, the same visceral, brawny muscularity and witty high spirits. Both artists know the rigor involved in making art look spontaneous, and, indeed, like Pollack’s paintings, at its freest, Mailer’s prose of the period resembles jazz improvisation: shooting from the hip, hopped up, a dialogic style that mocks and argues with itself (this, no this, or maybe this), the style approaches incantation, a trance state. The genius of Mailer’s journalism of the period cannot be overstated: it remains among the most exciting, funny, provocative, energetic American prose ever written.

Had he chosen to, Mailer could have continued writing in this vein for the rest of his career. Instead, in 1979, he wrote a thousand-page true life novel composed entirely of paragraphs such as this:

Then the family moved to Oregon and there were hardly any Mormons in the town. The church was above a laundry one time. He met people who believed Mormons had horns because they kept more than one wife. Stranger was just a kid but he would say, “I’m all for it.”

If the mark of a great artist is his ability to change while remaining recognizably the same (an affinity Mailer shares, explicitly, with Picasso), The Executioner’s Song represents a heroic emptying out of style on Mailer’s part. In an amazing act of literary ventriloquism and selflessness, the author, who had made himself and the filter of his consciousness his great subject for twenty years or more, in the process developing the period’s most distinctive and original voice in American literature, abandoned that style altogether to tell the story of Gary Gilmore and Nicole Baker.

In The Executioner’s Song, Mailer honors the material—this story of love and murder and the presaging of our insane media culture—by absenting himself, and the result is as bracing as cold water. It is only in retrospect that one fully appreciates how well-accounted for are all of Mailer’s obsessions—with courage, with violence, with spiritual grace and the prospect of reincarnation, with the American crazy quilt—in the story of Gary Gilmore. (One might argue that Gilmore’s brother Mikal had the tougher book to write in Shot In The Heart, the one that took the measure of the man, and reduced him to a punk.)

In The Executioner’s Song, Mailer honors the material—this story of love and murder and the presaging of our insane media culture—by absenting himself, and the result is as bracing as cold water. It is only in retrospect that one fully appreciates how well-accounted for are all of Mailer’s obsessions—with courage, with violence, with spiritual grace and the prospect of reincarnation, with the American crazy quilt—in the story of Gary Gilmore. (One might argue that Gilmore’s brother Mikal had the tougher book to write in Shot In The Heart, the one that took the measure of the man, and reduced him to a punk.)

And, for the critics who claim Mailer couldn’t write women, I give you exhibit A: Nicole, a genuine American heroine: the apotheosis of every young Jerry Springer trailer park mom, but with the soul of an Anna Karenina. She is a magnificent creation, Mailer rightly loves and admires her, and it is the love story between her and Gary that provides the book with its noble, tragic dimension. But The Executioner’s Song gains much of its power, too, for being another kind of love story. “Re-reading the bulk of my work in the course of a spring and summer, one theme came to predominate—it was apparent that most of my writing was about America,” Mailer writes in the preface of The Time of Our Time. “How much I loved my country—that was evident—and how much I didn’t love it at all!”

In The Executioner’s Song, Mailer’s love of “the indigenous American berserk” (to borrow a felicitous phrase from Philip Roth, now, officially, the Last of the Mohicans), is given full flower. The bifurcated structure of the book—Part I, Western Voices, tracing the history of the Mormons, the story of Gary and Nicole; Part II, Eastern Voices, the swarming in of the lawyers and hustlers and media men as Gary becomes a death row cause celebre—allows Mailer to take it all on. This is a vast and terrifying book of bone and blood and silences (note the double-spacing between each paragraph, a silent push into nowhere, as flat and empty as the Utah landscape). The word is tossed around without discrimination, but The Executioner’s Song is a masterpiece. If Mailer himself devalued and disavowed it to a degree because he did not perform the original research nor originate the project (Lawrence Schiller did), that hardly matters. If one wishes to understand America, this is a book to place on the small shelf beside The Scarlet Letter, Moby-Dick, and Gatsby.

He couldn’t do plot; he didn’t know the meaning of the word concision (witness, Harlot’s Ghost, his thrilling, immersive, 1,300-page doorstop of a novel of the CIA that ends, ominously, with the words “To Be Continued”); he could go windy and woolly and ruin his best insights and intuitions by attempting to codify them into theory; he had obsessions excremental and nasal (no American writer has a more highly-developed sense of scent); and was in firm possession of a grab-bag of favorite, tick-like words and constructions (“existential,” “dread,” “hip,” “technology,” “plastic,” “corporation,” “ontology,” “the imperatives,” use of the double negative); in a career of more than thirty books, perhaps a third of them were written under threat of guillotine by the tax man and the alimony schedule (“When, oh when,” Martin Amis once lamented of Mailer’s career, “will all the kids grow up, all the wives remarry?”); but these failings are mostly faults of excess. His oddest books, his curiosities and failures (Marilyn, Tough Guys Don’t Dance, Ancient Evenings, A Portrait of Picasso as a Young Man, The Gospel According to the Son) hold more interest than many a fine writer’s greatest successes. As Denby suggested, even at Mailer’s most infuriating, “it was still hard for anyone of normal curiosity to give a negative answer to the question, ‘Haven’t I learned something about myself and my country from this man?’”

In her review of Marilyn, a “rip-off with genius,” and a “book filled with bad vibes,” the great film critic—and Mailer champion and bete noir—Pauline Kael, summed up many of our feelings: “About half of Marilyn is great as only a great writer, using his brains and feelers could make it. Just when you get fed up with his flab and slop, he’ll come through with a runaway string of perceptions and you have to recognize that, though it’s a bumpy ride, the book still goes like a streak.” Then, capturing the live wire intensity of Mailer’s literary performances better than any critic I’ve seen: “His writing is close to the pleasures of movies; his immediacy makes him more accessible to those brought up with the media than, say, Bellow. You read him with a heightened consciousness because the performance has zing. It’s the star system in literature; you can feel him bucking for the big time, and when he starts flying, it’s so exhilarating you want to applaud.”

Well, applause is what we should be hearing, rather than the strangled note of apology creeping into the obituaries. (And what a fate for Mailer! To have his career entombed in The Times by Michiko Kakutani, “the one-woman kamikaze squad” herself!) In the present win-lose climate of American life, Did Mailer do it?, the obit writers demand. Did the blowhard literary angel deliver the big book he claimed he had in him from the start?

Mailer lived long enough to see the victory of the things he most despised: the ubiquity of plastic, television sitcoms, strip malls, Kleenex-style architecture, technology, a two-term president worse—dumber and more malevolent—than Reagan, the Pied Piper of the eighties, a war more fraudulent and ideologically confused than Vietnam, the subsuming of rebellion into the very lexicon of advertising (i.e., when everyone has a tattoo, tattoos mean nothing), the triumph of the corporation, an uglier, more cramped and conformed country, one in which literature holds little currency, a debased, dumbed-down culture that cannot possibly accommodate the kind of wild ambivalence a career and personality like Mailer’s suggests. “Of all my contemporaries I retain the greatest affection for Norman as a force and as an artist,” former head butting partner Gore Vidal graciously offered. “He is a man whose faults, though many, add to rather than subtract from the sum of his natural achievements.”

In these pages I have tried to give some impression of the author whose work opened up the widest possibilities for me. Of all the great post-war authors, Mailer was there first with the most, and American life is left a less interesting place with him gone. “He is the greatest,” said Muhammad Ali, Mailer’s self-professed hero, the champ with whom the author went running one beautiful night in Zaire. “I don’t know if he can float, but he stings with his words.” And so, the tale of the tape: The Naked and the Dead, Advertisements For Myself, The Armies of the Night, Miami and the Siege of Chicago, The Prisoner of Sex, Of a Fire on the Moon, The Executioner’s Song, Harlot’s Ghost. Norman Kingsley Mailer: the champ, undefeated.

—Andrew Lewis Conn is the author of P (Soft Skull Press, 2003).