The Prison Suit: Incarceration during China’s Cultural Revolution

16.02.11

Throughout prison literature, there are recurring themes: the simplification of life, the caging of the spirit, the appreciation for the things which in freedom we take for granted. For many Western readers, literary knowledge of prison life comes from one of two universes: the Soviet Union’s Gulag and our own American prison system. The former conjures thoughts of political oppression, the frozen tundra, and the mythically hard Russian spirit. The latter plunges the reader or viewer into a world of racial tensions and physical and sexual violence. This is perhaps fitting if one takes a look at current incarceration numbers: the US is number one, Russia is number three.

Throughout prison literature, there are recurring themes: the simplification of life, the caging of the spirit, the appreciation for the things which in freedom we take for granted. For many Western readers, literary knowledge of prison life comes from one of two universes: the Soviet Union’s Gulag and our own American prison system. The former conjures thoughts of political oppression, the frozen tundra, and the mythically hard Russian spirit. The latter plunges the reader or viewer into a world of racial tensions and physical and sexual violence. This is perhaps fitting if one takes a look at current incarceration numbers: the US is number one, Russia is number three.

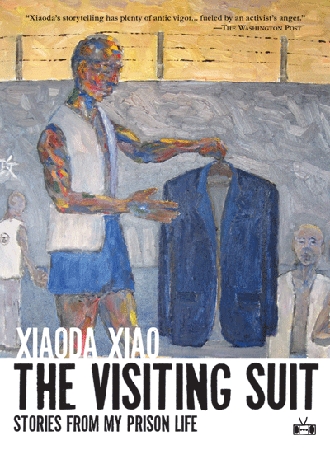

As other reviewers have pointed out, conditions inside the prisons of number-two-ranked China are relatively unknown. There has been no Chinese Solzhenitsyn although many of the stories of dissent in modern Chinese literature come from the Cultural Revolution, a nation-wide mental prison that has been presented in memoirs and movies such as Jung Chung’s Wild Swans, Zhang Yimou’s To Live, and Yuan Gao’s Born Red. It is with this uncertainty that one enters the world of Xiaoda Xiao’s The Visiting Suit.

Readers familiar with the literature of the Cultural Revolution will recognize the endless political meetings, self-criticisms, and attempted re-education of the prisoners. When the narrator writes a thought-report essay, hoping for a reduced sentence for his criminal trespass, he does not play the lexico-political games correctly and is put into solitary confinement because of it. By choosing the wrong words from Mao’s Little Red Book, he leaves himself open to criticism though there is little explanation for why his written thoughts are dangerous.

There are constant power plays among the prisoners to be made “lead prisoner”: today’s favorite might be next month’s outcast. There is the constant struggle for the “right thinking” that often never comes.

Those familiar with the prison in literature will recognize the cramped conditions, the slop, the boredom of incarceration, the counting of the days. Prisoners seem to wish for three things: to eat comfortably, to crap comfortably, and to be able to have sex comfortably. When the prisoners are treated to lard on the Spring Festival (the holiday known in the US as Chinese New Year), even an ardent vegetarian will feel their mouth water after a year’s worth of porridge with strips of cabbage or bits of pumpkin thrown in.

What one finds most surprising about the narrative is the recurrence of love in this world of men. Sex is an oft-treated subject in prison literature. The narrator does not ignore the reality of cooped-up, oversexed men: he mentions the pornographic chatter of the male prisoners, alludes to the homosexuality of some relationships, and does not try to hide his own libido. The men’s prison is located right next to a women’s prison and when the inmates get together to collect the harvest, hanky panky ensues.

Still, the subtlety with which Xiao expresses male desire is impressive and, in our contemporary world of readily available pornography and sexualized advertising, it’s his description of longing kept utterly private that is particularly beautiful. It is striking to read of how a boat woman’s lips move the narrator. When he dreams of his girlfriend’s smile, he longs just to sleep in so that he can continue to dream of it. When he becomes a guinea pig for medical experiments, the fact that the female nurses run their fingers along his skin makes it all seem worth it. In a period where perfume was an unheard of luxury, the narrator describes Little Flower, one of the prison’s female employees and the beautiful smell of her skin. Xiao’s narrative is powerful and convincing enough that when the narrator hides in order to hear and watch two women near the outskirts of the prison, the reader feels for the prisoner sating his need for the feminine.

Xiao’s book came together as a collection of short autobiographical stories which eventually grew into this complete memoir. Although the narrator is far from a neutral figure and one sympathizes him as he confronts the absurdity of his sentence, he is often placed in the background. We see him like the narrator of Dostoevsky’s House of the Dead, a vessel for the stories of the other prisoners.

One prisoner, who feels the scheherezadic power of stories very directly, tells stories of his youth to the other prisoners in his work group instead of holding the political self-criticisms and employs the tactics of the legendary Arabic storyteller. He tells his stories each night and cuts them off at tantalizing points, which guarantees him an audience from night to night. Even a guard is drawn into the fold.

While the other prisoners do not use stories to any direct advantage, what propels the reader through text is the same thing that helps the prisoners to continue: the quest for the next story. Once a prisoner knows another’s story, they sympathize, as do we. One of the greatest mysteries, both for readers and those inside the narrative, is the silent prisoner, a former head honcho in the local Communist party. How did he come to be there? How can he stand to remain silent? What injustice could have possibly been so great as to render him mute?

The eponymous suit is the greatest embodiment of this idea, the closest thing to a story in physical form that the prisoners have. The blue cotton jacket that one of the prisoners wears every time that his wife comes to visit draws in his fellow inmates and guards alike. They invest in the upkeep of the suit along with the prisoner and live vicariously through him when his quiet, demure wife visits. They know little of his story, but their imaginations fill in the details.

By the time the reader approaches the story of the suit, deftly placed at the end of the book, he has felt himself trapped in the cells along with the other prisoners. Sympathy with the suit and all who surround it is possible and this, ultimately, is Xiao’s literary accomplishment. After several well-crafted chapters of prison prose, he holds up a piece of cloth that would have meant little at the beginning of the narrative and shows it as a symbol of unity, beauty, and hope.

____________________

Buy Xiaoda Xiao’s The Prison Suit from Two Dollar Radio.

Related Articles from The Fanzine

Rob Tennant on Obsessive, Empathetic Mapping of Raleigh, NC.

Jamie Gadette on the Dehumanizing Effects of Sam Pink’s Person