The Marvelous Museum – Orphans, Curiosities & Treasures: A Mark Dion Project

21.12.10

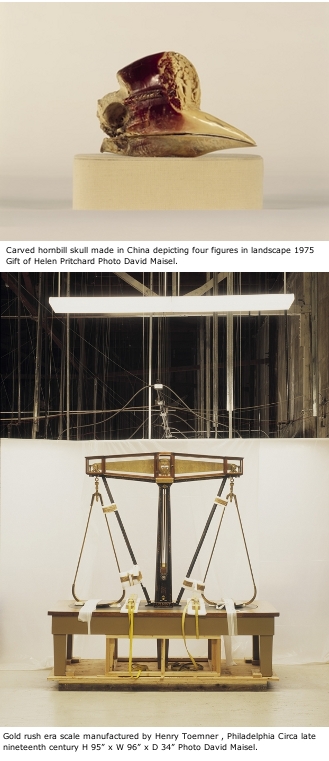

This book is an object. It’s also a collection. It’s something like a museum itself, and moreover, a museum’s basement, closets, and offices, as well as the exhibit halls. We get a sense of the contents of the museum as a museum worker might get to know them. Artifacts partially or wholly obscured by the trappings of their administration and protection. Rich objects glow bleakly under fluorescent light, atop simple pedestals of moving blankets and shipping crates, in David Maisel’s photographs. The museum is painted as a morgue of objects, a hospital ward, or as Dion and friends would have it: an orphanage.

This book is an object. It’s also a collection. It’s something like a museum itself, and moreover, a museum’s basement, closets, and offices, as well as the exhibit halls. We get a sense of the contents of the museum as a museum worker might get to know them. Artifacts partially or wholly obscured by the trappings of their administration and protection. Rich objects glow bleakly under fluorescent light, atop simple pedestals of moving blankets and shipping crates, in David Maisel’s photographs. The museum is painted as a morgue of objects, a hospital ward, or as Dion and friends would have it: an orphanage.

There is an amazing old photo in here of blind children exploring Eskimo objects by touch. Their blank eyes peer absently in no direction in particular, as they feel up the mannequin of a fur-wrapped Eskimo girl wearing the same ghostly expression, while the seeing teachers hover protectively behind. The accompanying real-life horror story by Peter Jacoby (great stuff!) tells, in part, of a family of Inughuit people from Greenland brought from the Arctic in 1897 to live as a display in the American Museum of Natural History. Four of these six people died within a month. Seriously. The loose arrangement of images, objects, and stories provided by Jacoby leaves room for the imagination to give that child mannequin a real human skeleton. The hands of the blind white explorers could almost feel through her skin the lingering tremors of an aborted culture. This is a dark orphanage indeed.

A piece by Rebecca Solnit within the Marvelous Museum casts California as “Nothing but an Orphanage.” She anecdotally records impressions left by objects from the Oakland Museum of California’s art collection, which speak to a voluntary self-orphaning undertaken by California’s settlers. Here we find a Chinese railroad worker’s portrait, Muybridge’s survey photos describing the remoteness of the Bay Area from other points of western civilization, political cartoons of 49ers traveling in from around the world, a 1942 school group portrait by Dorothea Lange where about 80% of the kiddies raise hands to proudly show they weren’t born in California. The biggest orphan prize for this big book of orphans would have to go to the portrait of Ishi, the last of the Yahi people, who remained after no one else on Earth understood his ways and language. In a nearby poem by Gary Snyder, this voluntary orphaning is an imperative for we bashful inheritors of western civilization: “I hunt the white man down in my heart. /…they won’t pass on to my children. / I’ll give them Chief Joseph, the bison herds, / Ishi, sparrowhawk, the fir trees, / The Buddha, their own naked bodies, / swimming and dancing and singing / instead.”

In a lighter sense, Dion talks about orphan categories in collections such as these: forgeries and fakes are an example, things out of date with current technology or exhibition vogue, and hybrids that could be in multiple categories, like a hornbill beak that is also a decorative Chinese snuff bottle. The Oakland Museum itself we understand as an orphanage of orphaned collections, built out of the rubble of three smaller museums back in the summer of ’69, by forward-thinking architects and citizen rabble-rousers. This includes the surreal Snow Museum, a whacky mansion full of big game trophies, kooky docents, and so much more, whose “requiem” is sung admirably here by Marjorie Schwarzer. The Oakland Museum’s resulting combine of art, nature, and human history is indeed a unique hybrid, as museums go.

So in what sense is all of this a Mark Dion Project? Dion’s work investigates how material objects store knowledge, and how they transfer that knowledge when we collect, categorize, arrange, and display them in museums. His contemporary takes on the curiosity cabinet have been exhibited widely, sometimes, as in Oakland’s case, using the collections of the museums that show them (like the Weisman Museum for example), or using objects from nearby archaeological digs undertaken by Dion’s teams of artists, students, and scientists (like the New England Digs and Tate Thames Dig projects). Really, the hybrid Oakland Museum is so totally up his alley that they couldn’t have possibly chosen anyone else to lend the contemporary arts seal of approval to their present renovation and reinvention.

So in what sense is all of this a Mark Dion Project? Dion’s work investigates how material objects store knowledge, and how they transfer that knowledge when we collect, categorize, arrange, and display them in museums. His contemporary takes on the curiosity cabinet have been exhibited widely, sometimes, as in Oakland’s case, using the collections of the museums that show them (like the Weisman Museum for example), or using objects from nearby archaeological digs undertaken by Dion’s teams of artists, students, and scientists (like the New England Digs and Tate Thames Dig projects). Really, the hybrid Oakland Museum is so totally up his alley that they couldn’t have possibly chosen anyone else to lend the contemporary arts seal of approval to their present renovation and reinvention.

There is a great interview of Dion here by Lawrence Weschler, prompted by well-chosen quotes from a range of sources, where he speaks to the magic touch an artist like him can bring to a dusty museum like this. People working in these museums, according to Dion, are interested in doing the same things as he does, namely, intervening in conventional exhibition strategies with an “irritating” unexpected element. “They don’t have the same freedom though. In fact that’s why they invite someone like me: I can do things they’d like to but can’t.” Elsewhere he says that he always tries to work in collaboration with museums, not against them, as in the art-historical genre of institutional critique. Institutional Caress might be an apter term for the craft of Dion and other artists like Fred Wilson and David Wilson, who are trying to make museums “better, more democratic, more complex, more interesting, more loving…” If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em kind of thing. This has its merits, albeit opportunistically convenient to be on the side of those in power and in possession of a lot of money, let us acknowledge.

Speaking of cash, this museum-scale book from Chronicle has a pricetag of $75, so in this reviewer’s opinion, you might be better off waiting until it shows up in a library book sale or flea market 40 years from now, improved with a patina of its own to match that of its contents. But if you can’t wait until you’re retired and snoozing by a woodstove in the country, this is certainly worth shuffling through. The book comes in a box along with several envelopes full of museum object-portraits printed on loose sheets of heavy cardstock. These card objects, one gathers, are meant to be arranged as the reader likes throughout the book, to introduce more randomness yet to the mish-mash. Honestly though, it seems as if the cards are designed specifically to be lost. Off they will inevitably go into the world on adventures of their own, to accumulate new stories, and to enter ever new and changing collections. Such is material existence.

The accompanying show of Dion’s collection interventions is at the Oakland Museum of California through March 6, 2011. The interventions themselves are actually not documented in the book, it seems, so you have to close your computer, leave your office, and go over there to discover them in person. Time will tell just how much tactile conceptual art exhibits about museum collections — or books about the same for that matter — can remain relevant in the face of an enemy so pervasive, so devious, and so effortless, as our beloved/hated internet.

____________________

Mark Dion at the Oakland Museum. The Marvelous Museum at Chronicle Books.

Related Articles from The Fanzine

Gean Moreno on Assume Vivid Astro Focus