The Last Warlock: A Brief History of Clark Ashton Smith and The Golden Age of Weird Fiction

05.04.09

“In one sense it is a mere truism to speak of the evocative power of words. The olden efficacy of subtly woven spells, of magic formulas and incantations, has long become a literary metaphor; though the terrible reality which once underlay and may still underlie such concepts has been forgotten.”

“In one sense it is a mere truism to speak of the evocative power of words. The olden efficacy of subtly woven spells, of magic formulas and incantations, has long become a literary metaphor; though the terrible reality which once underlay and may still underlie such concepts has been forgotten.”

—“The Necromantic Tale”

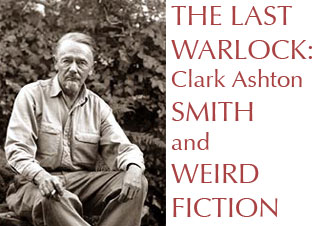

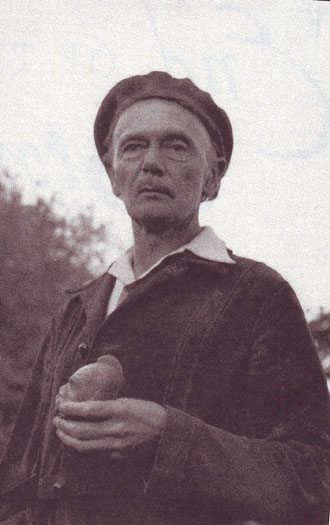

The first time I saw a photo of Clark Ashton Smith he was holding a carven stone head that looked like it had either come from outer space or was created by some ancient civilization. He wasn’t holding it for the benefit of the photograph; but like a slightly nerdier Indiana Jones, it appeared as though he could have been on an overgrown and dilapidated altar from which it had been stolen centuries ago…

And his eyes, not looking at the camera, not idly staring into space, but fixed on some point in the distance. Combined with his esoteric writing style, it was apparent that this person was truly touched by something mysterious. It later turned out that the strange object is one of many original carvings created by Smith himself. But the mystery surrounding the man was not decreased. The stone head was a product of his later life when carving and painting had overtaken his career as a writer. A career built from tales one is unlikely to encounter in most bookstores across the U.S., tales of a quality that made Clark Ashton Smith arguably the greatest practitioner of weird fiction in the world.

Just outside the city of Auburn, California, near what is today the Eldorado National Forest, is Boulder Ridge. Smith lived most of his life here, in the house he helped his father build in 1902. Today, not far from Auburn, lives Scott Connors, Smith’s biographer and the man considered by many to be the foremost expert on Smith’s life and career. “There are still a number of people who knew Clark living around this area, although they’re starting to pass away,” Connors says. “Generally speaking, they regarded him as a good friend; as somebody who was a little bit otherworldly at times; somebody who lived life on his own terms without making a lot of compromises.”

An only child, Smith was, from a young age, introspective and extremely fearful of crowds—characteristics that added to his imaginative output and also contributed to a largely solitary existence. “He had what almost amounted to a phobia regarding crowds,” says Connors. “He actually was accepted to the Placer County high school after he completed grammar school. This is back when going to high school was not automatic. He went for the first couple of days and the experience was just so hard on him, not academically, but socially, from being around so many people, that he and his parents thought that he’d do better by educating himself.”

What Smith lacked socially he made up for with a curious and attentive mind. He taught himself French and Spanish, read the 13th edition of Webster’s Dictionary and studied carefully the 11th edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica. By fourteen he had already written a short adventure novel called The Black Diamonds. Lost for years, the story was recently published by New York’s Hippocampus Press. However, it was primarily poetry that interested the young Smith. He fell under a sort of apprenticeship with writer and poet George Sterling and briefly moved among the circle that included Ambrose Bierce and Jack London. In 1925 he self published a book of poetry called Ebony and Crystal, which featured what would become Smith’s most famous poem, “The Hashish Eater,” also known as “Apocalypse Of Evil.”

What Smith lacked socially he made up for with a curious and attentive mind. He taught himself French and Spanish, read the 13th edition of Webster’s Dictionary and studied carefully the 11th edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica. By fourteen he had already written a short adventure novel called The Black Diamonds. Lost for years, the story was recently published by New York’s Hippocampus Press. However, it was primarily poetry that interested the young Smith. He fell under a sort of apprenticeship with writer and poet George Sterling and briefly moved among the circle that included Ambrose Bierce and Jack London. In 1925 he self published a book of poetry called Ebony and Crystal, which featured what would become Smith’s most famous poem, “The Hashish Eater,” also known as “Apocalypse Of Evil.”

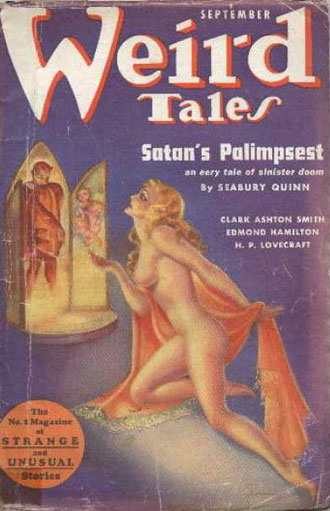

In the years between the two world wars, magazines such as Weird Tales, Amazing Stories, Black Mask, and Wonder Stories were just some of the pulp fiction rags that introduced America to a new type of weird fiction. These publications and others like them, trafficking in tales of horror, fantasy, and science fiction, made up a specific genre in a fiction market that was entirely dominated by magazines. “The markets that paid were the short fiction markets,” says Jeremy Lassen, editor in chief of San Francisco’s Night Shade Books. “Basically, magazines ruled the fiction world. Popular magazines at the turn of the century had circulation figures that dwarf Newsweek, Time, and People.”

This golden age of magazine publishing, vastly different to today’s mass media gauntlet of celebrity worship and news snippets, was short lived. “Essentially the nail in the coffin of that was the paper shortages during WWII,” says Lassen. “But radio and television also played a huge role in decentralizing short fiction as the primary means of popular entertainment. Weird Tales and the pulp magazines came along just as magazines––as the centerpiece for popular culture––were going away. Many of the general fiction magazines folded pretty early in the century, but because there wasn’t a lot of weird fiction in radio and movies, the niche magazines, whose circulation was smaller than the general magazines, actually lasted longer.”

Night Shade, which is run by Lassen and founder Jason Williams, is located about 120 miles southwest of Auburn. In 2006 they published the first edition of a five volume set encompassing nearly all of Smith’s short fiction work. Volumes two and three followed shortly after with the remaining volumes set to be released later this year. These editions are the first time such a comprehensive collection of Smith’s fiction have been published, and they form the centerpiece of the company according to Lassen.

“Mr. Smith was sort of the Holy Grail for Night Shade Books. A lot of his stuff had fallen into the public domain and we told the estate we wanted to do a five volume set of all of his fiction. When we first starting pursuing the project Smith was not very available. There was a British paperback ‘best of’ and an Arkham House hardcover ‘best of,’ and that was all that was in print when we first started the company back in 1998-99. We’d been pursuing this for maybe 8 or 9 years before we got the first book published. It was a titanic struggle to get the right editors and to get the estate to agree to it.”

One of those editors was biographer Scott Connors. “I had an opportunity to bring his fiction back into print in a correct edition and I grabbed it,” Connors says.

Despite the success of his early poetry collections, by the late 1920’s the short fiction market became Smith’s main source of income. “During that time you had the revolution in poetry that Ezra Pound, T.S. Elliot, and Harriet Munroe had ushered in. It was almost completely antithetical to the type of highly imaginative quasi-traditional poetry that was exemplified by Smith and his friend George Sterling,” explains Connors. But Smith’s use of poetic language overflowed into his prose writing as well, his dark imagery becoming perfectly infused into tales of ghoulish rites, sorcery, the macabre, and outer space.

Despite the success of his early poetry collections, by the late 1920’s the short fiction market became Smith’s main source of income. “During that time you had the revolution in poetry that Ezra Pound, T.S. Elliot, and Harriet Munroe had ushered in. It was almost completely antithetical to the type of highly imaginative quasi-traditional poetry that was exemplified by Smith and his friend George Sterling,” explains Connors. But Smith’s use of poetic language overflowed into his prose writing as well, his dark imagery becoming perfectly infused into tales of ghoulish rites, sorcery, the macabre, and outer space.

The pulp magazines of the early 20th century have come to be known as proving grounds for writers like Jules Verne, H.G. Wells and, later, Ray Bradbury. But of all the pulps, Weird Tales was the most well known (the magazine still publishes today). And among Weird Tales readers, as well as the weird fiction public in general, Clark Ashton Smith, Robert E. Howard, and H.P. Lovecraft were the three giants. The men never met in person, but maintained cross-country letter correspondences vast enough to fill volumes of books. Though coming from very different family backgrounds, Lovecraft and Smith shared much in common. Both were self-taught and both had been inspired early on by The Arabian Nights. Lovecraft was perhaps the most grounded in Gothic traditions of horror. Howard, forever to be known for his creation of Conan The Cimmerian was the premier battle strategist and adventure writer. Howard worked in several types of fiction, including horror, detective, and cowboy western, yet he was always adept at putting his characters (especially Conan) in the creepy settings of diabolical mystic danger. Ultimately though, it is Smith who would become most well known for use of setting and creation of environment.

As weird fiction emerged from the Gothic traditions of Lord Dunsany and Edgar Allan Poe, the discoveries of Einstein and the development of global travel opened new realms of science and world politics. Lassen explains: “Among the entire weird fiction circle, writers were very much enraptured by the idea of unraveling a new layer, a new perception of reality. Lovecraft himself was an amateur astronomer and I think there was that undercurrent particularly among the ones who were dabbling in science fiction markets. The 20th century was a time when the world and the universe got immeasurably big compared to previous centuries. It had become big, scary and dangerous.

“Prior to Lovecraft, Smith, and this circle of Weird Tales writers, horror fiction was firmly in the Gothic mode. When you talk about classic weird fiction, one of the things that ties it all together is that they were doing horror fiction but without the traditional furniture: H.P. Lovecraft imagining other dimensional outer planetary forces from beyond, the alienation and minuscule nature of humanity, or Smith playing around with the ideas of relativity, all these things were not traditional furniture for horror fiction. I think that’s why a lot of the weird fiction writers still resonate so strongly.”

Though not as avid a practitioner of science fiction as Lovecraft and Smith, Howard too could be viewed through this spectrum: Conan, the primordial Western man possibly representing America’s new found global influence and power.

Like Lovecraft, who created a whole mythology around a group of ancient god-beasts known as “The Great Ones,” Smith based many of his tales around invented worlds with their own background histories: the imagined future land of Zothique, the lost continents of Poseidonis and Hyperborea, and the medieval forest of Averoigne. Perhaps Smith’s most legendary attribute as a writer, the ability to conjure these worlds out of thin air as if he had been there, is made even uncannier by the fact that he was living in relative isolation. He also seemed unusually well versed in such esoteric subjects as medieval sorcery and necromancy.

Like Lovecraft, who created a whole mythology around a group of ancient god-beasts known as “The Great Ones,” Smith based many of his tales around invented worlds with their own background histories: the imagined future land of Zothique, the lost continents of Poseidonis and Hyperborea, and the medieval forest of Averoigne. Perhaps Smith’s most legendary attribute as a writer, the ability to conjure these worlds out of thin air as if he had been there, is made even uncannier by the fact that he was living in relative isolation. He also seemed unusually well versed in such esoteric subjects as medieval sorcery and necromancy.

Scott Connors explains: “You have to keep in mind that the 11th edition of the Britannica was probably the best one ever done. There was a very detailed article about magic and witchcraft inside there. Smith bought, especially in the 1930s, a number of books on occultism. He owned several volumes of Montague Summers and Lewis Spence. Samuel Loveman, a poet from Cleveland who knew Hart Crane, and was also a close friend of Lovecraft, engaged in correspondence with Smith through their mutual friend George Sterling. Loveman owned a bookstore and he would send Clark whole boxes of books and these would include some occult titles.”

Though heralded for his in-depth description of environments, Smith has occasionally been criticized for a lack of character development. Yet, the often-overlooked fact is that some of his best work includes characters who find themselves drawn into circumstances where even the most sinister of situations can be regarded with a dark humorous slant. Some, like the moneylender in the “The Weird of Avoosl Wuthoqquan” meet their end as victims of their own greed. Others are lost to naive human ignorance in an unforgiving universe, as in “Seedling Of Mars.” Some find themselves in twists of fate involving the divide between ancient witchcraft and Christianity: the former pupil of a deranged necromancer who returns to aid a country monastery against his former master in “The Colossus of Ylourgne”; the monk who finds himself abandoning his vows of celibacy in the arms of a pagan priestess in “The Holiness of Azedarac.”

And though many of Smith’s protagonists die in a gruesome manner, there are the rare instances when the hero of a tale finds an agreeable outcome in the company of a woman. Similar to Howard, Smith’s fictional world often presented women alternately as both temptresses and worthy companions. In the real world his female relations are described by Scott Connors as “very successful.”

Between the years of 1929 and 1933, Smith was at his most productive and wrote more stories for Weird Tales than any other writer. In 1933 he self- published his own zine of short stories called The Double Shadow and Other Fantasies. And yet, over the following forty years, as the legend of Howard and Lovecraft grew, drawing fans and recognition from around the globe, Smith remained in relative obscurity.

Between the years of 1929 and 1933, Smith was at his most productive and wrote more stories for Weird Tales than any other writer. In 1933 he self- published his own zine of short stories called The Double Shadow and Other Fantasies. And yet, over the following forty years, as the legend of Howard and Lovecraft grew, drawing fans and recognition from around the globe, Smith remained in relative obscurity.

So what happened? Connors and Lassen offer slightly different version of events. According to Connors: ”One, he didn’t die as young as either of them did. He actually lived for thirty years after he essentially quit writing fiction. His books were coming out during his lifetime, and while that made him more accessible to one generation of fans it didn’t quite create the same mystique.

“In 1933 Smith’s mother, Fanny Gaylord, had an accident involving boiling water being poured over her leg. His father was already very frail due to high blood pressure. So all of the domestic chores, as well as nursing his parents, fell upon Clark. And that basically prevented him from writing more stories during that time period. What helped was that Weird Tales had a very large backlog of stories that got published. Plus, at that time Hugo Gernsback of Wonder Stories owed him money [that was] never paid. [Smith] had to actually sic a lawyer on him. Clark was actually one of the few to get most of what he was owed.”

Lassen looks at it from a more general perspective: “There’s only so much room for any kind of giants of an era. Smith was always the poor stepbrother to people like Lovecraft and Howard. He was the odd fish. He was more like Lord Dunsany or William Hope Hodgsen, kind of more ethereal night lamp type stuff. I guess Lovecraft spoke more to the alienation of the 20th century. The insignificance of man and all that. Whereas Smith was purely in the romantic tradition—he was a poet first and foremost. There’s always a sense of wonder about Smith’s work. It’s kind of strange to think that Smith missed his era.”

Other incidences may have contributed to Smith’s semi-retirement as well. The deaths of his friends must have had some effect. Robert E. Howard took his own life in 1935, and two years later Lovecraft was dead. Shortly after, Smith abandoned writing fiction for the most part. At the age of 61 he married a woman named Carolyn Jones Dorman and the couple moved from his house in Auburn to Pacific Grove, California, though he maintained the cabin and property rights. In 1957 arsonists destroyed the Auburn house. Today, no original traces of the original home are left. The place where Smith wrote most of his greatest stories has vanished.

With the growth of film and television and the advent of paperback book anthologies, the golden era of the genre magazines ended. And though the tradition of weird fiction continues, Jeremy Lassen admits something has been lost: “Science fiction/fantasy is a declining literature in the broader sense of pop culture, I think, in part, because [science fiction has] conquered the world. Back in 1982 there were one or two big science fiction films a year if you were lucky. Pretty much every video game that comes out these days is a science fiction plot. Everywhere you look there are science fiction conceits and ideas that 25 years ago were not mainstream.”

With the growth of film and television and the advent of paperback book anthologies, the golden era of the genre magazines ended. And though the tradition of weird fiction continues, Jeremy Lassen admits something has been lost: “Science fiction/fantasy is a declining literature in the broader sense of pop culture, I think, in part, because [science fiction has] conquered the world. Back in 1982 there were one or two big science fiction films a year if you were lucky. Pretty much every video game that comes out these days is a science fiction plot. Everywhere you look there are science fiction conceits and ideas that 25 years ago were not mainstream.”

And yet, as so often occurs when an art form becomes oversaturated by the mainstream, the true practitioners have gone underground. Lassen continues, “I think there’s been a micro-explosion in genre fiction recently with low production value zines. Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, Electric Velocipede, Flytrap, and Trunk Stories…. These are these low budget staple-bound zines that are publishing really some cutting edge short fiction when it comes fantasy, science fiction, and horror.”

Over the last ten years Clark Ashton Smith’s work has been creeping back into popular culture. Though, as Scott Connors points out, it is rare for obscure heroes to get their rightful due: “Probably one of the better examples of Smith’s resurgence is how willing Hollywood is to rip him off. Did you read ‘The Seed From The Sepulcher’? Did you see the movie or read the book The Ruins? Take a look at that and tell me you don’t see some rather interesting similarities. Watch Danny Boyle’s movie Sunshine. When I saw Sunshine, I called up Arkham House and Smith’s literary executor, and told him ‘Hey, you gotta get a lawyer.’”

As Boyle is now an Oscar winning director after moving on from co-opting Smith (along with secreenwriter Alex Garland) to co-opting Bollywood, the actuality of a successful lawsuit seems unlikely. And yet, combined with further publications of his work, such incidences seem to indicate that Clark Ashton Smith, like his friends Howard and Lovecraft, will continue reaching out to us from the grave.