The Impulse of the Irr: Darby Larson’s Irritant

28.05.13

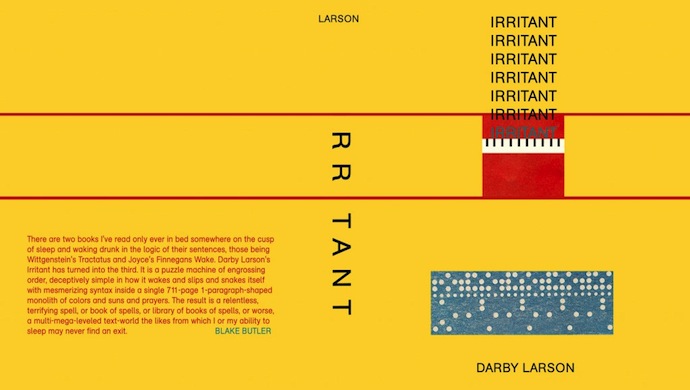

- Irritant

- Darby Larson

- Blue Square Press

- 624 pp.

- $25

When Ben Spivey, editor of Blue Square Press (an imprint of Mud Luscious Press), sent me the galleys of Irritant by Darby Larson, I wasn’t expecting the form to be quite what it was. What it is: a 600+ page paragraph––sort of. One immediately looks at the text and thinks, “This is Steinian,” or, “This is going to be difficult to get through.” Due to length, the book is daunting. But once you get started with it, it becomes easier to read, and, as Blake Butler recently noted, its “intentionality” is what propels it along. Irritant doesn’t so much have a cast of characters (though there are figures that appear) as much as it has an impulse––not without intention, mind you, which makes it work––in the form of the “irr,” short for “irritant,” I’m assuming. And what this “irr” does is move through a cartography of the imagination. Guy Davenport would have loved this! I thought. It’s a geography, and not without its twists and turns that make it move steadily, though with vectors and (again) intention, toward a commonality of thought that one can find, oddly enough, universal. Because of the intricacy of the images that Larson employs, the book is universal in scope, I think. Here’s a little bit more, using quotes where appropriate, to give you a sense of what I mean:

The irritant appeared in back of the truck and the rest is the moon on the back of the sun. The mirrored blue ate smoothly. Okay! Is that okay said something extra exasperatedly. The irr crawling on its elbowthumbs in front of this porch gave the porch of the water a yawn. The artichoke and the mirrored man awake next to the covered water slept for something extra. The man felt like sighing. So the trampled uterus slept while the irritant gave the slept uterus an artichoke for its cough? The man wore the heart of the irritant and there was little left in it.

So much is packed into a length that approximates about half a “traditional” paragraph, but is embedded, of course, within Larson’s story. It’s a sexual scene, of course, replete with innuendo and birthing––almost. The irritant is (and continues to morph in and out of these roles) both man and woman, and also, oddly, child. Is the irritant a creative urge? One could aptly guess so. Does the irritant spend itself, giving and wasting its powers, as the Bard of Avon would have advised against? Yes, possibly. There are many ways to read the impulsive irr’s intentions throughout the text, and it’s just barely propelled enough along to give us a hint of what’s to come, but not so pressed forward (forcefully) that the text doesn’t leave room for surprises. I think it’s entirely possible to read Larson’s narrative as a story about creation and destruction, echoing (slightly) the old refrain of both capital and Hindu mythology: “create––sustain––destroy.” We recognize our own impulses, and hence receive (if that is indeed possible) the mirror that helps us see through these urges.

There’s humor, too. Later on in the text, Larson writes:

The man sandbagged the flowerpot to front and the flowerpot and the irr never felt him and the man never felt the irr and all was amusing. The sun and the moon twinkled. The irritant irrd the thing and the man in front to the flowerpot and front to the flowerpot laughed. Is okay. And the irritant lay softly still and pointed at the moon and the mirrored earth. So the other gave and slept with the heart of the man standing on the blanket for now.

When the irr relents a bit, and the world stills (which is just momentary), we have a calming sense of amusement, humor, jolliness to the plot. The irritant evolves throughout the text to the point of ceasing to irk the man and woman in the story. And we get the sense that when the irr relents, after birth, or after having been the parasite that it is, there is a peace that the story cannot hold onto for very long before the irr is back in action, making trouble or at least becoming the itch that everyone (you, too, you know you do!) scratches, whether creatively or personally, if those two interpersonal/intrapersonal realms can indeed be severed effectively.

“When will everything be soft and warm?” Larson’s narrator inquires. There’s very little respite in the text, which is what propels us forward. And as we find the irr to be both friend and foe, at various moments of text, we also move through realms populated by feathers and fire, balloons, sun, moon, and “other,” which could be the man or the woman at various times in the book, or something else entirely. Larson writes of mice, mirrored earth, a boy, an artichoke, a flowerpot, a carpenter, a piano, a chair, and other figures who make the irritant seem to be a creative process in action, something to disturb and to be disturbed, in turn.

The book ends with the following sentences:

Is there nothing left but the feeling of the one who went away and the carpenter smoking to get the flowerpot on his chair and point at the masked weather? The infant really. This is a showboat.

What do we make of these last lines? Is the irritant a show-off who wants to be recognized? It’s hard to say, but if the irritant is indeed a baby, an infant showboat, then we have much to learn about the way he or she evolves (evolution, not maturation). This cycle of sentences begins where it ends, in a sense, but it also gives us a cartography of images that can be made more durable in our minds by re-reading, and that is the best a book can ask.

__________

Irritant is available from Blue Square Press.