The Immediate Coldness and Failures of Language: A Conversation Between Thomas Moore and Grant Maierhofer

07.02.17

I first discovered Thomas Moore’s work in his capacity as Thomas Moronic at Dennis Cooper’s blog. I’ve developed several relationships with likeminded individuals this way. Although Dennis’s work there has often seemed devoted to showcasing work, I’ve always seen a running aside to the posts having more to do with the space itself: a gathering place as scattered and welcoming as the first attempts one might make into creating, or experiencing, the possibilities of art.

With the recent troubles facing the blog, its shutdown, I found myself thinking often about those individuals I’d met or briefly corresponded with on there, and the unfortunate possibility that without the space, those communions would simply peter out.

Because of this, as well as an established admiration for one another’s work outside of DC’s, I’d wanted to exchange words with Thomas Moore about this and more. In turn, with both of us having recent work out arguably bound to the initial experience of engaging either with Dennis Cooper’s blog, or Dennis Cooper’s writing, it seemed an OK moment to put together a conversation, having read one another’s most recent book, about anything at all that might crop up.

Moore’s newest novel, In Their Arms, published by Rebel Satori Press, is a brilliant model of an artistic vein he’s mined with immense heart for years. We’ll discuss more, of course, during the conversation, but at the outset I wanted that established.

The book of mine that we’ll be discussing is PX138 3100-2686 User’s Manual, published by Solar Luxuriance this November. Although it’s different in its makeup than Moore’s, both—I hope—are arguably having a conversation with writing on the internet in a similar manner, and both became available at roughly the same time, so there we are. -GM

Grant Maierhofer: I thought to start we might delve right into Dennis Cooper as a presence in both of our lives, either concrete or abstract. How did the recent confusion re his blog’s shutdown affect you? Now that it’s back, how are you feeling? Is there anything bound up in In Their Arms related to these matters you might like to open with?

Thomas Moore: My main feeling was just of concern and sympathy about the amount of work that Dennis had put into the blog and the chance that it could have all been lost. I don’t know if people always realize how many hours that he’s put into that project – it’s huge. And it’s served as this incredible underground encyclopedia for so many people. It was a huge relief when he managed to sort out the situation and it was also really cool to see how many people and places came out in support of it – which kind of signaled the important and pretty much singular place that it holds in culture.

I’m not sure if In Their Arms really relates to any of that particularly … although I guess it is very concerned with how people connect via the internet, which is of course, a link. And I think you’re right about both of our novels – although coming from different angles or aesthetic places – both having conversations with writing on the internet. When did you first start reading DC’s? And also where did PX138 3100-2686 User’s Manual start? Was it a planned out idea or did it come from a set of experiments?

GM: I think I started reading DC’s around the time I started reading HTMLGIANT, maybe a bit before by accident when I’d discovered Dennis’s writing in print. This would’ve been 2012 or so, maybe earlier, and as with most online discoveries I spent a good month or two backtracking through most of it—I always love that feeling of newly discovered piles of work.

The user’s manual started as a collaborative project with a musician, but we wound up heading in different directions and it was set aside for some time. I’d been reading stuff like Dictee, or Cassandra Troyan’s Throne of Blood, as well as Tan Lin’s work, and felt drawn to this multiform, fragmented text. As a whole, it was planned out and conceived of as a book, but there are a ton of disparate experiments throughout as far as composition, arrangement, or variations in media and form to get at a similar theme of brokenness—being sawn—and violence.

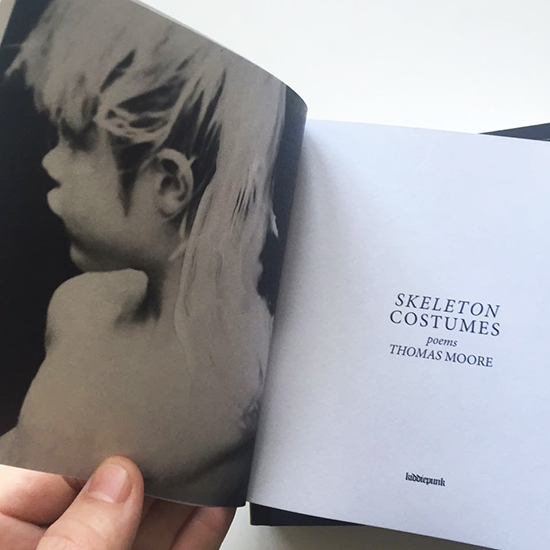

Recently you’ve published a range of material, from the haikus in Skeleton Costumes to this, a more cohesive novel that still engages the subject matter apparent in that earlier collection. I was wondering, while reading In Their Arms, whether these are projects conceived from the outset as projects, or whether you’re just kind of consistently working in this vein and putting things together afterward?

TM: Skeleton Costumes came out of In Their Arms, actually. I started In Their Arms a good while back and worked on it for a long time, which I know is odd considering it’s such a slim novel – I actually took out thousands of words in the edit – there are so many outtakes. One of the sections that really wasn’t working was this particularly violent set of scenes that I couldn’t get to balance with how I wanted the novel to work, so I took it out but was still really obsessed and drawn to working with it – the events I was trying to portray. I tried a load of different things, and one of them ended up being a short set of haikus that ended up being the starting point for Skeleton Costumes – and the narrative of that book started there. In Their Arms was a very definite project, which took a long time to work through and realize properly.

How does it work with your stuff?

And one thing I wanted to ask about with regards to PX138 3100-2686 User’s Manual is something about the theme of disconnection, which jumped out at me in a really interesting way when I was reading your book. I’m thinking of lines like “I wanted to watch myself fall apart in public” and “I’d like to die and smile at my corpse when I see it down below there” and “Witness this as mere compliment to another melted sequence of thought, an image here to augment feeling, a silence here to disconnect the experience from itself.” Were you purposely thinking about writing of this disconnection? It seems to link to the thoughts about writing on the internet in some way …

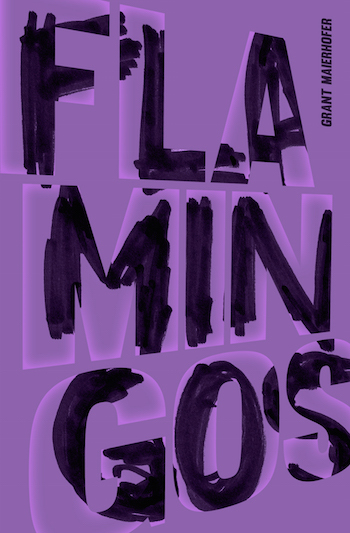

GM: As far as projects and how it all can come together, lately it’s been more about embracing in the moment interests and finding a larger context for them. Flamingos, for instance, began as a series of fragments where I wanted to process big changes in my life—I became a father this year, and reconciling that identity with whatever I’m interested in as a writer grew severely in 2016. I could see them fitting together in a larger project, but I couldn’t exactly see the larger project when I started writing. I think a lot about “permission” in writing, the notion that for a writer the most important thing is feeling free to write whatever comes. I felt out of place reading much of what’s encouraged for starting writers, but reading—and reading about—something like The Place of Dead Roads gave me a sense of freedom, of permission to vomit a bit in writing and trust that a context will somehow come together. Embracing that, and sitting down and starting, I guess, is how I’ve tended to operate.

I was very interested in disconnection with the manual. I think about a novel like The Last Samurai, for instance, and this search for language, for understanding, for knowledge. Wittgenstein too, then, and the notion of serious thoughtful work being best done as a dissection of the language in which its done. I wanted to work in that vein, but rather than writing something about language and disconnection and violence, I wanted to try and write something that was language and disconnection and violence, as garbled as that might sound. I was working with translation software and coding and the like to rework what I’d originally written—I’d done something similar with the first novel manuscript I wrote for Grobbing Thistle—into something considerably more fucked, but hopefully nonetheless new in its effect.

I wonder about structure with something like In Their Arms. The chapters here provide fascinating ellipses in experience, especially moving from the opening and this drunken/drugged stupor, into the more lucid experience of cruising sites—even the form, there, with conversations online offered almost like lines in drama, seems significant. Are these questions after the text has been written? Before? What relationship, I guess, does the organization of content have to do with how your sentences, paragraphs, even these fragments of memory or internetspeak, work for you as a writer?

TM: The structure was something that that I had an initial idea of when I started writing – the idea of loops and repetition, events and emotions turning in on themselves until they start to mean different things – and it evolved as I worked. The further I got into the book, the further the structure started to feel more apparent, so by the time I got to the editing stage, it felt clearer as to what I needed to work on and restructure. I think the way that I work is quite instinctual but with In Their Arms it was important to me that I trained myself in how to edit more and it turned out being a really interesting thing for me to do. I cut about half the book out. It ended up being very organized and purposely-structured piece of work.

GM: In his Paris Review interview DC talked a lot about pornography as a viable tool to inspire literature. Samuel Delany speaks to this too, about the “nest of scorpions” and the importance for him as a writer, as a person, to mind what people have deemed “transgressive” subject matter. Where does this come in for you as an artist? There are many vivid, or occasionally spare, or even The Sluts-esque pornographic episodes throughout. I guess I’m curious about where the line—if at all—exists between pornography and artwork, and whether thinking in such terms is useful to you, or not.

TM: I don’t know … There have been times when I’ve seen ideas in pornography and used them as an impetus for stuff in my work. I don’t know. With this new book, I think that I’m writing about sex but not pornography. I don’t think that there is much of pornography related to this particular work. I mean, pornography is a whole other, complicated discussion. In terms of writing about transgressive stuff – again, I’m not sure – I don’t choose to write about things because they could be considered “transgressive” – I just write about things that interest me.

GM: The other week, on Instagram, you were sharing images of artworks encountered at the London Frieze Festival. Going through these, I often felt the way I did while awash in the text of this novel. Your work does a brilliant job of rendering bodies, rendering vulnerabilities through text. I’m wondering to what degree that’s informed by your engagement with artwork beyond literature? My sense is we’d both prefer to treat it all as valid either as source material, or inspiration, would you agree? When crafting a novel, say, were you thinking solely of literary forms? Do formal concerns like that hold any value for you when you sit down to work?

TM: Yeah, I think that I definitely see or try to see everything as the same thing, as in, visual art, music, writing, films, TV, whatever – it’s all art and I find it really useful to think of it all in the same way rather than splitting it up into different categories or by medium or form or whatever. And I think because of this, my work is very much informed by artworks outside of literature – I was hoping that that would filter through into In Their Arms. I’m never solely thinking of literature. I’m a real enthusiast and try and see as many exhibitions as I can, and try and keep up with artists that I like and hear new music all the time. It’s important to me. I’m really interested in mood and tone, and when it comes to being inspired by something or excited by an artwork, I really don’t care what medium it’s coming from at all. And there are always so many artists to be excited about.

A line you wrote jumped out and seemed to relate to this: I can read derrida and not understand a thing. I can listen to drab pulsating music and understand everything. This is what I want. This is what I’ve made for me. It seemed to hint that writing wasn’t the be all and end all for you when it came to inspiration. It also made me think that perhaps you were also an artist who relied very much on instincts when it came to the create process …

What/who have you been getting excited recently art-wise?

GM: I’ve always watched immense amounts of television, likely too much, so that’s constantly something I’m thinking about in terms of influence, inspiration and the like. I’m very obsessed with Samuel R. Delany in all of his forms. I think his pornotopic novels are the closest thing there is in fiction to what Foucault did as a writer, and I’ve never experienced anything quite like them. I’m also working on a project to do with the language of fascism, in particular with regard to Richard Girnt Butler and the Aryan Brotherhood in Idaho, so I’ve been on a constant loop of reading with Gass’ The Tunnel, and Bolaño’s Nazi Literature in the Americas. I teach composition right now so I return frequently to Geoffrey Sirc’s English Composition as a Happening as inspiration for that, and my writing more generally. Tehching Hsieh, always. I think of writing as a performative act mostly, as printed texts as distillations of a series of performances and mindsets for writers, so figures like him and Chris Burden loom large for me, larger often than “writers” themselves.

GM: I’ve always watched immense amounts of television, likely too much, so that’s constantly something I’m thinking about in terms of influence, inspiration and the like. I’m very obsessed with Samuel R. Delany in all of his forms. I think his pornotopic novels are the closest thing there is in fiction to what Foucault did as a writer, and I’ve never experienced anything quite like them. I’m also working on a project to do with the language of fascism, in particular with regard to Richard Girnt Butler and the Aryan Brotherhood in Idaho, so I’ve been on a constant loop of reading with Gass’ The Tunnel, and Bolaño’s Nazi Literature in the Americas. I teach composition right now so I return frequently to Geoffrey Sirc’s English Composition as a Happening as inspiration for that, and my writing more generally. Tehching Hsieh, always. I think of writing as a performative act mostly, as printed texts as distillations of a series of performances and mindsets for writers, so figures like him and Chris Burden loom large for me, larger often than “writers” themselves.

I’m constantly curious about the use of literature and art these days. I tend to want to argue with the Wilde notion that art is useless and that’s perhaps as it should be. Your work, to me, fits into a field currently being dug out by presses like Kiddiepunk, and writers like yourself, Mark Gluth, Dennis Cooper, Jeff Jackson, and many more. If not use, what do you see as the impetus for this vein of work in our world? I’ve always felt, for instance, that Cooper’s work goes a long way in reevaluating the larger culture’s hypersexualization of younger females, by focusing more on these River Phoenix-y dreamscapes and the murder of young boys. Do these things seem significant to you? Does motive factor in? (I guess I’m doubly curious because your writing always strikes me as incredibly of-the-moment, wanting to use language to interrogate lived experience now. Is that just how you, as an artist, respond to existence? Or is there also a political/social edge to what you do?)

TM: I mean, I’m a fan of all those writers that you mentioned. I think they’re all wildly different as well as sharing some influences and stylistic things. It feels like there are so many awesome writers creating work at the moment and the last few years have been really exhilarating because of that. There have been some really exciting presses popping up and giving new, cool, different voices and opportunity to be heard.

I have no real explanation for why I write apart from that I feel compelled to do it. I think I definitely work through how I feel about certain things that happen in my life or in the world with writing.

My writing can be of-the-moment sometimes, but more than not, it isn’t. I’m incredibly interested in how hyper-emotional states can be rendered in writing, and the way language can and can’t do that – often the immediate coldness and failures of language help create this amazing friction between intent and the actual end result. So sometimes my writing may seem of-the-moment but it’s actually because I’m sort of obsessive when it comes to portray painful and overwhelming feelings and situations, and it’s often more language based than people may think. Any motives I have are to do with playing around with language and the work itself.

Is there a political bent to your work? I don’t know why but I feel like with this new book in particular, there seems to be some kind of investigation into the notion of control …

GM: I’ve thought more in political terms about the work lately. I think, starting out, I just wanted to convince myself that there was some way for me to write things at least relatively close to what those writers I admired wrote. Now, though, I see fiction as a very viable political or social or public form, in its relationship to the constructedness of language. If someone agrees that our language is built, made up, a sort of fiction, then it stands that more abstract, fluid forms of language-generation could have the most to say about language as an oppressive thing, or an uplifting thing, or a device with which we can make sense of our existence. This book, I guess I was interested in science fiction to an extent, machines as oppressive, dominating forces having their own language. But, in turn, I think about books like Hogg, and the oppressive tendency there, this relentless language and subject matter. If read by way of apolitical means of critique, that book might seem like pornography for its own sake; but the language is so jarring, so relentless, and so fully-wrought, so considered, that it seems to beg to be read as an extension of the subject matter, a comment on violence, oppressive forces, gender and sexuality. I like this mode of operating very much. Work that doesn’t hold your hand to get its point across. The difference, say, of interpreting a more vile, unpalatable text like Romper Stomper versus American History X. Both have much to say about fascism, but the latter seems to reassure viewers constantly that “all is well, we filmmakers would never court these ideas”. I’m skeptical of that, I guess. I like it when writers trust that I’m capable of reading of vile figures without their comeuppance occurring in the text proper. I want to—at least sometimes—process evils that exist, or violences that exist, without back-patting or editorializing pointing to things being OK. If there’s a political vein, then, it’s somewhere in this muddled paragraph, and that’s what I’m interested in as a writer—more often than not as a reader as well.

Many writers—and this might be where our projects here cohere best, actually—are trying to convey the internet, the way it crops up in our daily lives, or the way language is altered online. You do an excellent job throughout In Their Arms of depicting, interrogating, and utilizing the rhetoric of the “hookup site,” I suppose you’d call it. I’m wondering whether this was a natural process for you, whether it felt cumbersome, and how you feel about other attempts to render the modern world in writing?

TM: I was thinking about this the other day and I was wondering if my take on the internet had anything to do with the fact that my generation was one of the last to grow up without it. The internet came into more everyday use when I was in my late teens and I was able to sense a very definite before and after moment. For me, I like the theatrics of online speak, which I think a lot of people don’t really think about or realize that they’re engaging in. There is representation upon representation which you can read in so many ways. I love peeling the skin off of online conversations and holding it up to a light so you can see the different lights and shadows that are cast through it. It never feels cumbersome because I find it so interesting to pick apart.

As to thinking about how other people use their work to capture the modern world … I guess in terms of the internet, Ryan Trecartin is an artist who springs to mind straight away who has done really amazing things in trying to show how people communicate – his work is incredible. Then I’ve really enjoyed the visual artist Dave Hilliard and some of his recent work. Dennis Cooper did an amazing job with The Sluts. And I feel like there are a lot of musicians who have played with the different layers that the internet suggests.

Still, a lot of the way I go into writing about that stuff is instinctual, and then I work my way through how I feel about it as I write. How about you? Do you go into that kind of thing with set things that you feel like you want to highlight or point out? Or is it a natural thing that occurs?

GM: As a reader, or even just an audience member for artwork in any form, I’m interested first in modes of representation—be it language in fiction or poetry, globs of paint in visual artwork, compositions and moods in film, or production qualities in music and the like. As a result, when I work, that’s where I start. I think in my very early writing I was much more naïve—I likely still am—and I thought about feeling, sentiment, broader ideas like representing selfhood or something. Now I’m far more comfortable, and happier actually, to dwell in language itself, to think of words and then—if ever, sometimes—questions of a story being told, a “character” or anything like that. I don’t know that I think about representing modern times or modes of speech except in an angry metalhead teenager’s manner: I want to use the internet and computers and distorting influences so the writing can suck its own throat, et cetera.

It might be because of Skeleton Costumes, but I felt very tempted to read these sections as sort of koans, fragments all working toward some larger whole. I’m wondering if you have thoughts on this, on the fragment overall, or its use for you as a writer in this text? Number 17, in particular, stood out to me as indicative of this larger project, “— A photograph of an American Apparel sign./— A gif of Lindsay Lohan smoking a cigarette and blowing the smoke to the side./— A photograph of a pale girl with Sea-Punk style coloured hair./— A cat on a fluorescent pink and green background with ‘FUCK YOU’ written in Comic Sans.” This is a shorter excerpt of the list in #17, but I’m wondering maybe what you think about this kind of thing as a reader, in addition to a writer. I kept thinking of work like Why Did I Ever, or maybe even something like Rules of Attraction, where the book as a whole seems to operate in a very particular way. I realize I’m asking way too fucking much about structure and the like, but I kept returning to that in reading.

TM: The book really operates as a whole. I had to pick a couple of pieces to give to websites as excerpts recently and I realized that there were only a few sections that seemed to work as standalone pieces, which I kind of liked because it felt like all the structuring work that I’d done had worked, you know? I think that piece that you mention is definitely one of the pieces that works as a standalone piece. I like the fact that the book feels like a whole thing to me. Although any piece of work is built up of lots of different ideas melded together. There are sentences that I think stand on their own, and maybe paragraphs but I think the larger you go, the more the sections feel linked together.

How important to you is the idea of structure when you are working on a piece? Do you pre-plan much or work with things as they fall into place organically?

GM: Structural qualities present themselves in second, third, and later drafts, but with certain projects I definitely set out with an ideal form in mind—whether I adhere to it or meet whatever mark I’ve imagined is the question, I guess. I seldom think in terms of wanting a reader to experience things in a particular order, as I’m far more interested in honing in on a project and moving through it that way, sentence by sentence, page by page, and I guess through this larger, skeletal changes will occur.

I kept thinking of this as a recursive work, as this compounding thing, where alterations are made throughout to complicate and complicate the body of text until by the end we’ve revisited the notion, the phrase, of “warmth,” but it’s been completely warped, debauched throughout by the fragments of text, and occasionally the ideas behind them—I’m thinking of the chat section devoted to HIV-seeking here, and this image of your narrator curled up and writhing at what started as a more playful foray into stuff like Grindr—all of this built a novel that made me want to return, to revisit, to reconsider sections I’d read more speedily getting lost in your sentences, versus those that made me laugh, or those that felt genuinely shocking. Is this just me imposing a sort of Finnegans Wake model on things, or are you interested in texts like that? Do you want readers to revisit, to grow with the work? Is this something you seek out when reading?

TM: I’m really happy to hear you say that. The book operates on a series of loops – some small, and some larger – I mean, you can loop the book as soon as you finish it – so I’m really into the idea of someone reading it over a few times. I mean, I’d never tell anyone what to do, and if reading it once feels like enough then that’s cool. But I’d definitely say that there are a lot of things within the text that will reveal themselves the more you read it – I like to think of it as feedback or drone, which if you listen deeply enough to you can end up hearing different patterns and frequencies within. I think that the structures become more apparent the more you scratch off the skin.

Have you got an ideal vision of how someone would read PX138 3100-2686 User’s Manual? It feels like there’s a balancing act of a seemingly impenetrable skin, with a much more emotional punch at the heart of it. Again, I’d suggest it’s a piece of work that rewards multiple reads.

GM: There’s much made, so far as I can tell, these days, about how and to what end people are reading anymore. Amid the din of this, I have found myself often turning to work like Finnegans Wake or even the writing of Vito Acconci, for the feeling it transmits of being awash in language. One might turn a page and pick apart every word, every line, and one might simply become lost in the swell of neologisms and portmanteaux—a feeling, I’d argue, similar to watching an entire TV series in an afternoon, or scrolling through certain websites. In my mind, the manual can function similarly. It can be read in sequence, with strong attention, and prove enjoyable—I hope—just as it can be plucked, page by page, for different, yet similar, ends. There are lines in here I’m happier with than just about anything I’ve written, as well as images and fucked sequences that seem to overwhelm and warp any aspirations I might’ve had as the writer of this text. I’d want it to be lived with, I guess, and read on the terms of the reader, respective to the sea of information pulling at their attentions. Read whole hog, I think it offers a grisly note, but parsed I hope it lends perspective to a violent mindset, and offers a slew of ways of reading our present state.