The End Zone Profanations of Chad Ochocinco

17.05.16

Chad Ochocinco had what it took to profane. I’m talking about rocking the pigskin like a baby. I’m talking about pretending to bribe an official. I’m talking about covering his Cincinnati Bengals uniform with a Mexican poncho and donning a sombrero. Nearly everything Eight Five did drew a fine from the National Football League office, for his subversive antics were interpreted as attacks on the sacredness of the game. They were indeed profane.

Philosopher Giorgio Agamben defines the profane in opposition to the sacred. The ancient Roman jurists regarded the sacred as that which has been set apart for use by the gods and is no longer able to be used by human beings in daily life. The profane then, by contrast, is that which was sacred but has now been returned, or reappropriated, to daily use. In football, an orange pylon demarcates a boundary of the field of play, and Chad Ochocinco reappropriated it as, of all things, a putter. That’s what I’m talking about.

Looking at the modern American ritual of violence football, it is easy to see what the “No-Fun League” considers sacred. We have the field of play, which only the players and officials may enter. We have the uniforms, which the players are prohibited from customizing or in any ways tampering with. We have the football, which must be inflated to a proper psi, regardless of the Golden Boy’s preferences. Consider the bodies of the officials themselves, whom the players are strictly prohibited from touching. These are objects made sacred for the duration of the ritual, and to use them for any other purpose is to profane them. Above all, it is the collector of memorabilia who worships the game and appreciates the sacred value of these ritual objects. So goes the congregation.

But the end zone celebration presents special problems for an institution that attempts to fully sacralize its objects. You see, when a player scores a touchdown, he’s excited. In 1965 when Homer Jones scored the first touchdown of his career, he had trouble containing his excitement. At first he felt the urge to throw the ball into the stands. Fortunately for his pocketbook, he remembered that then-commissioner Pete Rozelle frowned upon this fourth wall breaking gesture as a profane act. By instead directing his celebratory throw downward, Jones invented the spike. But Jones demonstrated his allegiance to “the game,” later expressing regret at having paved the way for profanations. “”Celebration is one thing, but a lot of it is mockery,” Jones lamented, “[…] if I’d known how it was going to turn out, I wouldn’t have done it.”

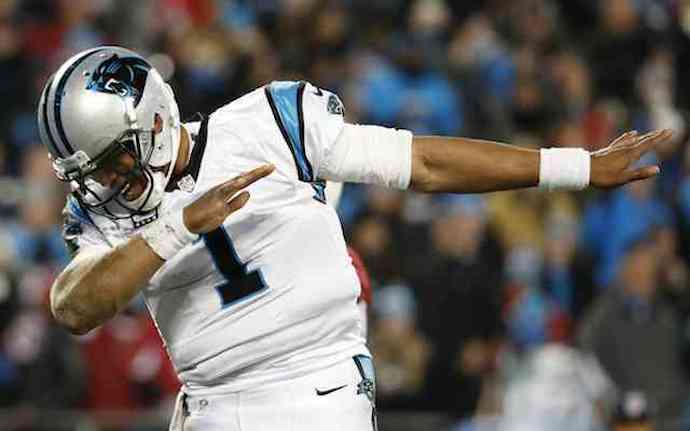

No, he wouldn’t have. You see, Jones, like many ambassadors for the game, feels that certain acts disrespect the game itself. The “mockery” alluded to by Jones may well be a critique of celebrations that elevate an individual player’s accomplishments and “brand” above the league’s. Yet, star players like Aaron Rodgers and Cam Newton have been permitted to have branding celebrations provided that they are extremely brief. Rodgers, whose “championship belt” celebration quickly turned into his lucrative Discount Double Check®, had no intention of mocking the league. Upon scoring, Newton playfully, and quickly, reveals that he is Superman and then gives the football to a lucky child. But the NFL does not actually have a problem with such celebrations, provided they do not detract from their own product.

Such actions draw neither penalty nor fine. So what then does the NFL actually dislike? Over the years, the league has enacted more and more draconian rules against end zone celebrations. One significant prohibition came in 1984, as they outlawed “any prolonged, excessive, premeditated celebration by individual players or groups of players.” The rule was ostensibly designed to stop the Washington Racial Slurs from their (really awesome) Fun Bunch dances.

Typically, the post-touchdown dance has not profaned the league, as it is awkward when performed to excess. Husky, loveable Ickey Woods expressed his joy through an elementary set of moves known as the Ickey Shuffle. But it was a celebration of the game itself. Likewise, Jamal Anderson’s Dirty Bird, an Atlanta Falcons fan favorite. Even coach Dan Reeves partook, sort of. Victor Cruz broke ground with a salsa dance in honor of his grandmother, and Ochocinco performed a very capable homage to Lord of the Dance. Aside from the spike, the end zone dance is perhaps the most popular type of touchdown celebration. But it is not dancing or self-branding that is truly subversive to the ritual of American football. If anything, it is the reappropriation of sacred objects from the field of play.

So it wasn’t until 2006, the year after Chad Ochocinco used the pylon as a putter, that the NFL banned props. Section Three, Article One, Rule G: “Using the ball or any other object including pylons, goal posts, or crossbars, as a prop.” Note that the oblong laced ball is consistently used as a prop for the purpose of spiking, yet this ubiquitous act is acceptable. Why? Perhaps as Olivia says in “Twelfth Night, “There is no slander in an allowed fool.” This implicit sanctioning by the league is also true of the Lambeau Leap, a celebration that clearly breaks the fourth wall yet is not intended or viewed as a profanation. It is for the love of the game.

Yet one can adduce examples of major transgressions to Rule G. Saint Joe Horn made an actual telephone call, from an actual telephone he had stashed under a goalpost. Cardinal Via Sikahema unloaded on the rival New York Giants’ crossbar cushion. These celebrations are not to be taken lightly as profanations. Though Sikahema claims not to have premeditated his punching bag workout, both gestures were indeed subversive. That said, their behavior was largely isolated to these profane incidents.

Terrell Owens, a repeat offender, is another story altogether. After one memorable score, Owens sprinted to midfield and took a dump danced on the Dallas Cowboys’ sacred star. After another, he pulled a Sharpie from his sock and signed the football—a clear violation of several rules at once. After another, he memorably snagged a fan’s bag of popcorn and thrust it into his facemask. Owen had guts. He had talent. He had creativity.

But there is only one player who truly recognized what it meant to profane. Only one man who knew what it meant to overturn the tables in the temple. Only one man who performed CPR on a football. Only one man willing to officially change his name so that the league would be forced to print his nickname on the back of his jersey. OCHOCINCO.