The 2007 New York Film Festival: A Preview

27.09.07

In a year as inhospitable as 2007 has been so far to intelligent mainstream American movies, the 45th edition of the New York Film Festival (NYFF), which opens to the public today, couldn’t have had better timing. Over the past nine months, some of the most compelling studio releases (Zodiac, Grindhouse, and Sunshine, to name three) have taken their licks commercially and critically even as audiences and reviewers have joined their hands over blockbuster fare so pointless and insultingly anti-cinematic (The Bourne Ultimatum) that it threatens to take us back to that blanched decade when Warner Bros. and Twentieth-Century Fox offered us, respectively, Doris Day and Jayne Mansfield, the latter via what was then state of the art Technicolor Cinemascope. Commercial American movies needn’t by law be vapid, predictable, meretricious or leaden. Right?

In a year as inhospitable as 2007 has been so far to intelligent mainstream American movies, the 45th edition of the New York Film Festival (NYFF), which opens to the public today, couldn’t have had better timing. Over the past nine months, some of the most compelling studio releases (Zodiac, Grindhouse, and Sunshine, to name three) have taken their licks commercially and critically even as audiences and reviewers have joined their hands over blockbuster fare so pointless and insultingly anti-cinematic (The Bourne Ultimatum) that it threatens to take us back to that blanched decade when Warner Bros. and Twentieth-Century Fox offered us, respectively, Doris Day and Jayne Mansfield, the latter via what was then state of the art Technicolor Cinemascope. Commercial American movies needn’t by law be vapid, predictable, meretricious or leaden. Right?

Perennially calendared on the heels of trendier jetset gatherings in Cannes, Venice, and Toronto, programming at the NYFF has long tended to reflect the marriage of convenience between its knowing cinephilic selection committee (which this year includes the Village Voice’s incomparable J. Hoberman) and the gravy tastes at Lincoln Center, the festival’s urban haute bourgeois venue. What this means—as another Voice critic Nathan Lee explained on Wednesday—is that the festival’s riskier independent and foreign selections (to say nothing of its under-publicized experimental sidebar or restored B&W choices, like John Ford’s 1924 western The Iron Horse) must be counterbalanced by an ample serving of middle of the road, Oscar-baiting fluff pictures. The happy surprise of 2007 is that two of America’s most established (if not establishment) directors have come to the festival with complacency-rattling smart bombs disguised as go-down-easy pop masterpieces.

That’s not to say that by comparison this year’s NYFF has a weak international field. It is true that the movie this reviewer has been anticipating most for the last seven months, Jacques Rivette’s Ne touchez pas la hache, finally got its North American premiere three weeks ago in Toronto and won’t hit a Manhattan theater until November. Neverthless, you can’t exactly complain about a NYFF playlist that includes new releases from Bela Tarr, Eric Rohmer, Jia Zhangke, and Hou Hsiao-hsien. Jia and Hou alone are considered among the world’s finest working directors. Unfortunately, because several of the most adventurous foreign pictures will not be screened for us journos until after press time, I can only tell you that I hear good things from colleagues who have already caught some of these films at other festivals.

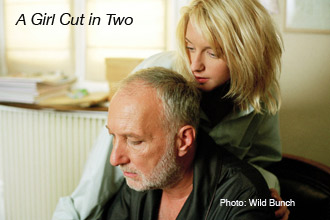

What I can tell you firsthand is that Claude Chabrol’s latest, A Girl Cut in Two, is a worthy companion piece to his Comedy of Power, which played here this past winter. While both films explore the convergence of mass media, sexual politics, and class warfare in contemporary France, Comedy’s Isabelle Huppert was an ironclad weathervane at the center of her public scandal. In contrast, in the most troublingly hot sex scene in awhile, Girl’s Ludivine Sangier walks across a floor, beatifically smiling, with a peacock feather up her ass. Sangier becomes in this moment and for the remainder of the movie an embodiment of innocence in a world corrupted by male privilege—the martyred equal of the donkey in Bresson’s Au hazard Balthazar.

What I can tell you firsthand is that Claude Chabrol’s latest, A Girl Cut in Two, is a worthy companion piece to his Comedy of Power, which played here this past winter. While both films explore the convergence of mass media, sexual politics, and class warfare in contemporary France, Comedy’s Isabelle Huppert was an ironclad weathervane at the center of her public scandal. In contrast, in the most troublingly hot sex scene in awhile, Girl’s Ludivine Sangier walks across a floor, beatifically smiling, with a peacock feather up her ass. Sangier becomes in this moment and for the remainder of the movie an embodiment of innocence in a world corrupted by male privilege—the martyred equal of the donkey in Bresson’s Au hazard Balthazar.

It’s Yank privilege, though, for which the NYFF has been designed—thus, Joel and Ethan Coen’s (presumably unorthodox) adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s Texas gunslinger, No Country for Old Men, Todd Haynes’s snarky, deconstructionist Bob Dylan biopic, I’m Not There, and most especially the opening night selection, Wes Anderson’s The Darjeeling Limited. Anderson’s latest concerns three brothers (Owen Wilson, Adrien Brody, and Jason Schwartzman) who prance through India by train, sporting customized Marc Jacobs-for-Louis-Vuitton luggage. I’ve never been a member of this dude’s hipster darling cult, and although The Darjeeling Limited’s casual retro-Orientalism is characteristically off-putting, I have to admit that this film is easily Anderson’s most emotionally honest work since Bottle Rocket. My unqualified hosannas, however, are reserved for Messrs. Sidney Lumet and Brian De Palma.

I can’t claim to be particularly objective about De Palma’s work (you’re telling me Carrie didn’t scar you when you were a kid?) and I realize I’m asking for trouble by saying this, but I can’t imagine seeing a more politically radical movie this year than his Redacted. Commissioned by the HDTV network and shot entirely on video, Redacted is a fictional account of the actual 2006 rape and murder of a fifteen year-old Iraqi girl by a group of American soldiers. Superficially, the plot resembles the director’s 1989 Vietnam pic, Casualties of War, and like its predecessor Redacted explores the conditions that produce war crimes. Redacted’s primary interest, however, is video—how it functions as the medium through which everything we think we know about this war passes. “The camera lies all the time, lies 24 times per second,” De Palma has famously said. And yet in Redacted, he defies us to deny the truth of what we see, no matter how unreliable the source.

I can’t claim to be particularly objective about De Palma’s work (you’re telling me Carrie didn’t scar you when you were a kid?) and I realize I’m asking for trouble by saying this, but I can’t imagine seeing a more politically radical movie this year than his Redacted. Commissioned by the HDTV network and shot entirely on video, Redacted is a fictional account of the actual 2006 rape and murder of a fifteen year-old Iraqi girl by a group of American soldiers. Superficially, the plot resembles the director’s 1989 Vietnam pic, Casualties of War, and like its predecessor Redacted explores the conditions that produce war crimes. Redacted’s primary interest, however, is video—how it functions as the medium through which everything we think we know about this war passes. “The camera lies all the time, lies 24 times per second,” De Palma has famously said. And yet in Redacted, he defies us to deny the truth of what we see, no matter how unreliable the source.

Lumet’s Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead isn’t nearly as ambitious or as obviously firebrand as Redacted, and probably that’s why it comes as such a gut punch, even if you can see the plot twists coming. “Now you know,” one character tells another late in the proceedings. “The world is an evil place. And some of us make money off of that.”

Like Don Siegel and Robert Altman before him, the 83-year-old Lumet is a television-incubated craftsman, and Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead doesn’t particularly break new formal ground. Fact is, it’s an old-school heist thriller, complete with elliptical narrative—a tribute to the kind of overlooked gems (e.g. Siegel’s own 1973 Charley Varrick) that Quentin Tarantino has been robbing blind his entire career. And yet Lumet compensates for his apparent lack of innovation with calm, this-material-isn’t-anywhere-near-played-out execution. The novelty, and sure the preposterousness, of Ethan Hawke and Philip Seymour Hoffman as brothers wears off pretty quickly. Both actors are in top form, and if you can’t muster the faith to believe in their love-hate sibling relationship, you don’t have any business going to the movies. Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead is the movie the Academy thought they were talking about in March when they praised Martin Scorsese to the heavens and gave him an Oscar for a twilight reunion tour cum gangster remake.

Like Don Siegel and Robert Altman before him, the 83-year-old Lumet is a television-incubated craftsman, and Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead doesn’t particularly break new formal ground. Fact is, it’s an old-school heist thriller, complete with elliptical narrative—a tribute to the kind of overlooked gems (e.g. Siegel’s own 1973 Charley Varrick) that Quentin Tarantino has been robbing blind his entire career. And yet Lumet compensates for his apparent lack of innovation with calm, this-material-isn’t-anywhere-near-played-out execution. The novelty, and sure the preposterousness, of Ethan Hawke and Philip Seymour Hoffman as brothers wears off pretty quickly. Both actors are in top form, and if you can’t muster the faith to believe in their love-hate sibling relationship, you don’t have any business going to the movies. Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead is the movie the Academy thought they were talking about in March when they praised Martin Scorsese to the heavens and gave him an Oscar for a twilight reunion tour cum gangster remake.

Notably, NYFF is also screening yet another version of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, this one called “The Final Cut.” It’s ironic to say the least that in a year when the festival is showcasing the vibrant work of two senior auteurs, it has also chosen to pay homage to a seminal classic by a once-promising director who these days churns out the kind of CGI pablum that even the Lincoln Center white hairs have no time for. A marriage of convenience, indeed.

Visit the New York Film Festival’s official site for screening dates and times, and stay tuned to Fanzine’s New York City listings for detailed reviews of recommended movies. Image on page one from The Darjeeling Limited, photo: James Hamilton. Thumbnail image from No Country for Old Men, photo: Richard Foreman/ Courtesy of Miramax Films.