That Kind of Trash: A Review of Ugly Girls

25.11.14

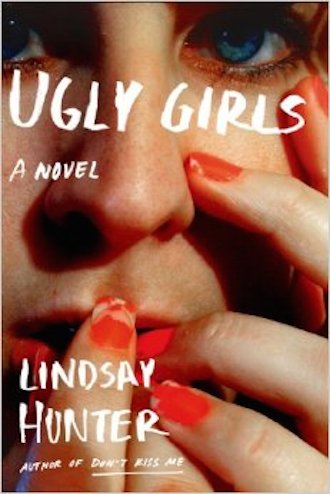

Ugly Girls

Ugly Girls

by Lindsay Hunter

FSG

240 pp

“You’re poor, but you don’t act like it.”

His name was Brandon, or Jason, or Justin, and he was on my bus in elementary school. The route looped from the school, maybe a mile across town, through two new-ish developments, past a few old stone farmhouses, and back to my neighborhood of twin houses and duplexes, where everyone’s mom worked, and the kids spilled shoeless into the streets until dark, unsupervised unless something or someone got broken. He lived in a house with a two-car garage, the kind that probably had a mudroom overflowing with sports equipment, more than enough bedrooms for everyone, hallways hung with photos of faraway family vacations. He had Umbro shorts and Adidas Sambas. He would have braces and a college fund, and no matter what he did as a teenager, he would be forgiven.

He was saying it because I had something new on, so it must have been around my birthday, which, aside from Christmas was the only time I got new clothes. I’d pick them out myself most of the time, and my mother would put them on layaway at the discount store until she had enough in her checking account to cover it. She was working then, but she didn’t make much, and wanted even less to spend it on us, when there were plenty of things she wanted that having children seemed to deny her. I was a kind of poor that happens in the suburbs. We ate best when we were on food stamps, rarely heard from my dad, and polite parents pretended not to notice that my mother always wore her sunglasses indoors. But I was smart, and I was clean, and I behaved myself, so I didn’t get lumped in with the other kids that grew up like I did, or worse. Except on the bus, I could pass for middle class.

Ugly Girls is about a lot of things – internet creeps, broken families, and the tenuous end of girlhood, when the only shred of innocence left is an ignorance of how the world fits together and how you fit into it. But Ugly Girls is also pointedly about the kind of trash I grew up being.

Lindsay Hunter’s first novel is set in a world of problems without clear solutions, a world where simply mustering the energy to fight is beyond most of the characters’ resources. I’ve lived in it. There’s nothing exciting about your mother bouncing too many checks at the same grocery store to go back, or the school losing your free lunch ticket for a few days. It’s a dull misery, a sting that lingers at the back of your eyes without ever turning to tears. It’s the sadness of a people resigned.

Ugly Girls is strung up on this kind of sadness. The plot hangs on it. The characters wear it heavy around their necks, and they strain under the weight of it. It’s the kind of sadness that turns you mean, ugly. Perry buries that ugliness under the kind of tenuous beauty that won’t work as currency much past thirty, while Baby Girl lashes out from behind hers like it’s riot gear.

Hunter’s characters stand tall with spines stacked with minutiae, each detail a vertebra. You can smell the Marlboro Menthol Lights on their breath, reach for the tiny smear of ranch stuck at the corner of a mouth. You can feel the emptiness of Baby Girl’s house, of her life with saved Uncle Dave, and her brain damaged brother, Charles, who was once her hero, and is now little more than her charge. Her vulnerability radiates out from under her oversized clothing, from behind her lipliner. It’s easy to understand how Jamey, the girls’ mysterious mutual Facebook friend manages to wedge himself past a layer or two of her armor, giving her just enough attention to sneak halfway past her suspicions.

Likewise, it’s easy to understand how cool Perry plays it with him. She’s is the more pragmatic of the two. She knows her value; she’s learned it on her back. Jamey paying her the kind of nagging attention she’s used to getting, buzzing like a mosquito out for blood, is just a nice little distraction from her life in an overstuffed trailer, where her mother, Myra, beerily fades into the background of her own life, and her stepfather, Jim, grows more and more exhausted by family he married and chose to love.

The manic energy of Hunter’s short fiction belied the measured pace at which she reveals the fraying relationships between Perry and Baby Girl, between the girls and their families, between having and losing hope in a world where you’re set to fail.

There’s a point early in the book, when Perry’s contemplating her mother’s sadness, her distance, and can only explain the cause as “everything and everybody.” In her world, life beats against you, like the ocean does a rock, taking a little piece each time, until there’s nothing left. No wonder she looks at he relationship to her mother as “just a midpoint on her timeline.” Each person, each event will eventually get swept away with the tide.

The year I turned thirteen, my mother married a man who wrote her letters. He came all the way to Pennsylvania from New Mexico, towing a broken car to our backyard, and sat, shirtless and stoned on our couch until she kicked him out. From March to October, his word was law, whether he was calling the nine-year-olds on my brother’s Little League team “faggots” or grounding us for every paranoid perceived disobedience. When my father remarried, it was to the kind of woman that has a pill for everything, the kind of woman who would rather join in than referee a fight between her daughters on the front lawn. I left as soon as I could.

Reading Ugly Girls felt like going home. I wasn’t safe, I wasn’t happy, but I settled in, got comfortable, and felt like a part of me hadn’t ever left.