Talk Show 5: with Maud Casey, Myla Goldberg, Karl Iagnemma, Christopher Sorrentino

26.11.07

TALK SHOW 5

TALK SHOW 5

Hosted by Jaime Clarke

Topic: Witness to History

Guests:

Maud Casey is the author of two novels, The Shape of Things to Come and Genealogy, and the short story collection, Drastic. She lives in Washington, D.C., and teaches at the University of Maryland. Visit Maud at www.maudcasey.com.

Myla Goldberg is the author of novels Bee Season and Wickett’s Remedy and the essay collection, Time’s Magpie. Her first illustrated children’s book, Catching the Moon, was published this past spring. Visit Myla at www.mylagoldberg.com.

Karl Iagnemma is a roboticist at MIT, and author of the short story collection On the Nature of Human Romantic Interaction and the forthcoming novel The Expeditions. Visit Karl at www.karliagnemma.com.

Christopher Sorrentino is the author of Sound on Sound, Trance, a finalist for the National Book Award, and the forthcoming American Tempura, a collaboration with artist Derek Boshier. His writing has appeared in Esquire, Harper’s, the New York Times, Playboy, and many other publications. He teaches writing at The New School in New York City.

––Name an historical event you wish you would’ve witnessed/participated in and why.

Casey: I would like to drop in Quantum Leap style (or maybe Journeyman is the more current TV reference, though I can only think of the excellent Kevin McKidd as Lucius Vorenus and I keep wondering whether McKidd as the Journeyman will travel back to himself, but I digress…) on much of the middle-to-late part of the 19th century in France to watch the burgeoning psychiatric culture, well, burgeon. More specifically, I would like to attend one of the Tuesday Lessons held by Jean-Martin Charcot at the Salpetriere Hospital in Paris and, more specifically still, I’d like to attend the one he gave on February 7, 1888 titled “Hysteroepilepsy: A Young Woman With a Convulsive Attack in the Auditorium.” For those not obsessed with the history of psychiatry, the Tuesday Lessons were the weekly public lectures Charcot gave on various illnesses, though hysteria became a frequent and major subject.

He would hold the lectures in the amphitheater of the hospital and he would have a patient there to, essentially, perform the illness up for discussion. In the transcript of the Feburary 7, 1888 lecture, Charcot writes, “Isn’t there something immoral about waiting and provoking such crises?” This is, in fact, what he goes on to do. He instructs, for example, an intern to touch the woman’s “hysterogenic point,” located conveniently under her left breast, in order to trigger the “epilleptoid phase” of hysterioepilepsy. Then he instructs the intern to compress the woman’s “ovarian region” with an “ovarian compressor belt.” Like so many trailblazers doing really weird things, Charcot kept elaborate records so drawings of an ovarian compressor belt, as well as pictures of women in the Salpetriere amphitheater, in all stages of hysteria and hysterioepilepsy, are easy to find should you care to check it out.

It’s all a bit grim––and my desire to be there may seem akin to wanting to see a bullfight in which the bull is replaced by a mentally ill woman––but the patient’s performance, its freak show aspects aside, is moving to me because it was exactly that, a performance, and as a performance, it was hers to perform. To look at the drawings and photographs of women whom Charcot had assigned this diagnosis is to see women translating their messy, amorphous pain (usually exacerbated by living in the Salpetriere) into something legible.

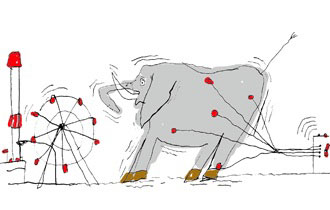

Goldberg: The electrocution of Topsy the elephant by Thomas Edison at Coney Island’s Luna Park in 1903. My motives for wanting to be there are kind of schizophrenic. The do-gooder time traveler in me wants to be there to let everyone there know what Edison’s true motives are for the electrocution, which I’d like to think would have had potentially far-reaching implications. I have no illusions about being able to save Topsy herself, but it would have been nice if her death could have revealed Edison’s black heart to the general public and brought recognition to Nikola Tesla, overlooked genius of the twentieth century. The wistful-tourist time traveler in me wants to be there because, either before or after the elephant goes down, I could enjoy Coney Island in its heyday. I’ve seen old films and postcards of Coney Island in the early 1900s and it was clearly the most beautiful amusement park ever.

Goldberg: The electrocution of Topsy the elephant by Thomas Edison at Coney Island’s Luna Park in 1903. My motives for wanting to be there are kind of schizophrenic. The do-gooder time traveler in me wants to be there to let everyone there know what Edison’s true motives are for the electrocution, which I’d like to think would have had potentially far-reaching implications. I have no illusions about being able to save Topsy herself, but it would have been nice if her death could have revealed Edison’s black heart to the general public and brought recognition to Nikola Tesla, overlooked genius of the twentieth century. The wistful-tourist time traveler in me wants to be there because, either before or after the elephant goes down, I could enjoy Coney Island in its heyday. I’ve seen old films and postcards of Coney Island in the early 1900s and it was clearly the most beautiful amusement park ever.

Iagnemma:I would have loved to have been a member of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Since I would have been useless as a hunter, canoeman, naturalist, or cook, I suppose I might have been Meriwether Lewis’s personal assistant. It would have been great for so many reasons: seeing the western US before it had been settled, interacting with Lewis (who was a great explorer and, by all accounts, an exceptionally smart man). Even hearing Thomas Jefferson’s stories, secondhand from Lewis, would have been wonderful.

Sorrentino: Not to derail the entire spirit of the thing, but I’ve never been more conscious of actually inhabiting history. “Interesting times,” etc. It makes me despair a little––a writer is in a better position than maybe anybody else to lodge a coherent protest, but it’s looking obvious that few people are interested in coherent protests or the action that should flow from them. There’s all this awareness of what’s going on politically, socially, economically, environmentally, and there seems to be very little way to participate other than as a willfully blind accomplice. Our participation begins and ends with The Daily Show.

––When and how did you first become interested in this historical event?

Casey: Charcot is one of those larger-than-life characters; he’s almost a parody of himself. I’m interested in the history of psychiatry and he looms large there. He was the first Professor of Diseases in the Nervous System and was at the forefront of neurology (it was just emerging when he started school). He was a plump fellow with no facial hair, often compared to Napoleon. He had a pet monkey who, I believe, dined with the family. His son fled an internship at his father’s hospital to sail a ship—the aptly named Porquoi Pas—on an exploration of the Northern seas, where he eventually sank near Iceland. There’s an island named after him (Charcot Island). So, Charcot Senior was the kind of father who inspired his son to go really, really far away from him and die doing dangerous things. He was not a simple guy and the combination of wanting to help (let’s study the problems of the mind) even as he’s treating his patients a bit like circus animals (let’s get really famous and lose track of the original, honorable goal) is, let’s face it, not so unusual. Interesting people doing groundbreaking things are, often, compelling complicated assholes. And then there’s the patient. Again, this notion of someone with anguish they can’t describe aiming to please a doctor in order to get help or attention or love is heartbreaking to me. The woman who was the “young woman with the convulsive attack in the auditorium” says at one point during that particular Tuesday lesson, “Mother, I am frightened.” Charcot’s response? “Note the emotional outburst.” But the woman’s performance in all of this is also strangely heartening. She’s doing whatever she can to get something.

Goldberg: I was watching a collection of Edison’s early films and one of them documented Topsy’s execution. I’d already known about the golden age of Coney Island, but hadn’t known that Luna Park’s debut year included the execution of an elephant as a publicity stunt. It wasn’t until years later that I learned the undercurrents of jealousy and greed that were the event’s secret motivating factors.

Iagnemma: Probably after reading Stephen Ambrose’s Undaunted Courage, which is a very engaging treatment of the expedition. Somehow I missed the PBS love-fest from a few years ago.

Sorrentino: Around the time that I heard a TV commentator in the days after the 2000 presidential election ask some expert or another whether he thought that Al Gore would “take the high road” and concede the election to Bush––there was something so marvelously Orwellian about the language, the sinuous suggestion that to contest the vote would be a ploy, a selfish act not in the interest of the American people or democracy. And of course this “expert” didn’t object; didn’t protest that there was nothing subversive or unsportsmanlike in letting the democratic process play itself out. It became clear to me that protofascism had at last established the kind of foothold it likes best: quietly persuasive, almost homespun, declaiming what Roland Barthes witheringly calls “the perfect intelligibility of reality.” The unchallenged use of that sort of language managed in two seconds to do what a loudmouth like Rush Limbaugh hasn’t done in twenty years.

––Name a player in the historical event whose motives aren’t clear and speculate about what the motives might be.

––Name a player in the historical event whose motives aren’t clear and speculate about what the motives might be.

Casey: Everyone’s motives are murky here. Charcot’s, the patient’s, and the audience. My own desire to crash this wacked-out party. The Tuesday lessons were spectacle as much as science, a freak show like any other. Come see the woman cower in a corner! Come see the woman arch her back! Come hear her beg for her mother! Charcot’s lectures and these live experiments with patients were about the emerging field of neurology, about scientific discovery and inquiry, about Charcot’s career (not surprisingly, his focus on hysteria has overshadowed a lot of the genuine progress he made) and his increasingly rotund ego. It’s unclear who this “young woman with the convulsive attack in the auditorium” was before she was that, but it’s likely her life was pretty rough at the overcrowded, unsanitary Salpetriere. Was this moment “onstage” a small moment of relief? Of rare attention? When I read the stages of hysterioepilepsy Charcot induces, I imagine someone dancing faster and faster on a table as the applause grows louder and the crowd in the bar shouts for more. I’d like to see her face—not her photographed face or her drawn face, her actual face. Charcot wants something from her and she’s providing it. Is she getting something in return? At another point, she says, “Oh! Mother.”

Goldberg: While Edison’s true motives weren’t general knowledge at the time, they were certainly clear to anyone working with him. I wish I could interview Topsy. She was executed after killing three of her handlers in three years. Considering that the last of these guys, J.F. Blount, had tried to feed her a lit cigarette, I suspect that the previous two were equally enlightened in their behavior toward animals. After J.F. tried to pass off his cigarette as a peanut, Topsy picked him up with her trunk and then threw him to the ground, killing him instantly. She didn’t run at him or knock him over; she did something much more deliberate. I love that. And I wish I could take her to a peanut bar, treat her to a pound of salted, and talk with her about it.

Iagnemma: Most historians seem to agree that Meriwether Lewis committed suicide in 1809, three years after the expedition’s conclusion, but there are still some who suggest that he might have been murdered. Lewis was a depressive, who had previously attempted suicide, but he left no clue about what happened that last night. Some commentators seem amazed that a man so rugged and accomplished could have committed suicide; but of course accomplishments don’t mean anything to a person suffering from depression. Lewis was probably just exhausted by life.

Sorrentino: Wouldn’t it be nice, or at least vaguely hopeful, if our current situation were rife with ambiguity, ironic Sophoclean trials of character, and Shakespearean doubt and uncertainty?

––If you could affect the outcome of the historical event, what would be different?

Casey: Though I know it’s against all the Quantum Leap, Journeyman, Back to the Future rules, ideally I’d like to rescue the young woman from a life of misery, bring her into the future where she could cast off the ovarian compressor belt and take a warm bath and some Valium. Though—and this is why I’m interested in this particular event to begin with—the impulse to diagnose is as potent here in the 21st century as it was in its nascent form back then. Who knows what kind of too-tight sweater her messy story would be stuffed into now? In Freud’s obituary of Charcot in 1893, he described him as Adam, the great namer of things. You, my dear crazy lady, are an hysteric. There’s a label to contain you and your wild contortions. A similar yearning exists these days to contain the wild, mysterious mish-mash of emotion, experience, neuroscience, to name it. And the flip side: to be contained, to be named.

Goldberg: I wish I could have been a small voice in the crowd watching Topsy go down. I wish I could have said, “You know why Edison’s making a big deal out of using alternating current to kill off this beautiful elephant? Because he didn’t invent it: his former employee, Nikola Tesla, did. Edison stiffed Tesla out of a $50,000 bonus for completely redesigning the company’s generators and then refused him a raise. Edison wants you to think that Tesla’s alternating current is dangerous so that you’ll continue using direct current, which is his much lamer invention.”

Iagnemma: If Lewis was murdered, then obviously this is the aspect that would change. If he wasn’t … it’s tempting to say that his suicide could be changed, but that doesn’t make a lot of sense. It would have been nice if Clark hadn’t been treated so poorly by the federal government. Aside from that it’s difficult to imagine what I’d change about one of the most successful expeditions in American history.

Iagnemma: If Lewis was murdered, then obviously this is the aspect that would change. If he wasn’t … it’s tempting to say that his suicide could be changed, but that doesn’t make a lot of sense. It would have been nice if Clark hadn’t been treated so poorly by the federal government. Aside from that it’s difficult to imagine what I’d change about one of the most successful expeditions in American history.

Sorrentino: What would be different, but alas won’t be, would be if the issues the current and all future national campaigns will address aren’t left for the candidates and their consultants to delimit. They fall into the deep sleep of their comfort zones and nobody in the press can bear to pull the comforter off them. Looking at all the wreckage George Bush has left in just seven years, I can’t believe that he and Al Gore spent the entire 2000 presidential campaign grappling over social security.

––What aspect of the event do you consider either overblown or under-appreciated?

Casey: Charcot and his Tuesday lessons are very much appreciated and discussed and criticized. They have been dissected, deconstructed, and otherwise fed through many an academic shredder. I first read a book about Charcot, specifically the photographs that were taken of the “hysterical” women he studied, in a class in college. The take home message was that Charcot was pure patriarchal monster, another too-tight sweater.

The truth is I don’t think I’d like Charcot much. I’d be rooting for the woman dancing faster and faster on the table. It would be hard to watch, this Tuesday Lesson on February 7, 1888, but I’m interested in the glimpse of relief the woman might have felt in being watched, in having her mysterious pain anointed with a name. Diagnoses are, after all, stories, and in its screwy way, the Tuesday lesson was a story about her. Maybe not her story but a story in which she had a leading role, which is sometimes better than no story at all.

Goldberg: Nikola Tesla was a celebrity in his day, but his name has been largely forgotten. He not only invented alternating current––which despite Edison’s national smear campaign became the international standard––but vied with Marconi for inventing the radio and was a pioneer in the development of radar technology. The fact that Edison’s name is so much huger than Tesla’s today makes sense, given that Tesla had no business sense and was eccentric enough to fall in love with a pigeon, but in a better world schoolchildren would be singing his praises and Tesla’s later vision of a system of free, wireless electricity for all would have made Thomas Edison’s name the quaint, historical footnote.

Iagnemma: The expedition has been written about so exhaustively that it’s tempting to say that it’s all a bit overblown. But what seems somewhat unappreciated (or at least less overblown?) is the scientific nature of the journey. Mostly this was Lewis’ work, collecting botanical and mineral specimens, and it completes the picture of Lewis as a writer/adventurer/scientist, the sort of man that seems to have only existed in the 19th century.

Sorrentino: September 11 is certainly overblown, or at least distorted. It’s become National First Responders Day. Whatever’s underappreciated will get its due, when we’re paying for it.