Talk Show 27 with Daphne Beal, Charles Bock, Emily Chenoweth, John McNally, Irina Reyn and Peter Trachtenberg

02.07.09

TALK SHOW 27: PAST INTO PRESENT

TALK SHOW 27: PAST INTO PRESENT

Daphne Beal’s first novel In the Land of No Right Angles, was published by Vintage/Anchor Books in August. Her fiction has appeared in Open City and The Mississippi Review, and she has published nonfiction in Vogue, McSweeney’s, and the New York Times Magazine. Her essay on Wisconsin was recently included in State by State: A Panoramic Portrait of America. Visit Daphne at www.daphnebeal.com.

Charles Bock is the author of the New York Times bestselling novel Beautiful Children. Visit Charles at www.beautifulchildren.net

Emily Chenoweth is the author of the novel Hello Goodbye. A former fiction editor at Publishers Weekly, her work has appeared in Tin House, Bookforum, the anthology The Friend Who Got Away, and various and sundry other publications. Visit Emily at www.emilychenoweth.com.

John McNally’s most recent book is Ghosts of Chicago, a collection of short stories. He is also the author of another collection, Troublemakers, and two novels The Book of Ralph and America’s Report Card. He’s edited six anthologies, most recently Who Can Save Us Now?: Brand-new Superheroes and Their Amazing (Short) Stories (with Owen King), and published over fifty short stories, three of which have received citations in Best American Short Stories. A Chicago native, he is an Associate Professor of English at Wake Forest University in North Carolina.

Irina Reyn’s first novel What Happened to Anna K., published in August 2008, will be out in paperback this May. She is also the editor of the anthology, Living on the Edge of the World: New Jersey Writers Take On the Garden State. She teaches writing at the University of Pittsburgh and divides her time between Pittsburgh and Brooklyn. Visit Irina at www.irinareyn.com

Peter Trachtenberg is the author of 7 Tattoos: A Memoir in the Flesh and The Book of Calamities: Five Questions About Suffering and Its Meaning. The latter combines journalism, moral philosophy, and personal essay to explore the way that individuals and societies try to make sense of sickness, war, injustice, and loss. He’s the winner of a Whiting Writer’s Award, an artist’s fellowship from the New York Foundation for the Arts, and the Nelson Algren Award for Short Fiction. He currently teaches creative writing at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington. Visit Peter at www.petertrachtenberg.com

––Name something from the past that you’d like to bring into the present.

Beal: Chuckwagons.

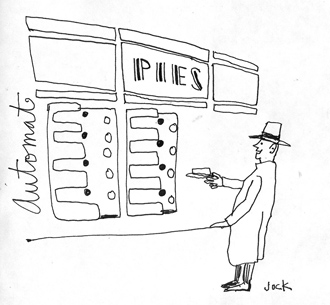

Bock: The automat. I don’t know if you remember these: but they started in the fifties and ran through the seventies. Basically it’s a cafeteria where all the food is inside machines. You put a dollar in the machine and a slotted door opens and behind the slot is a sandwich, or an apple, or what have you.

Chenoweth: I’m an indecisive person, and I couldn’t pick just one thing to bring back. So here are a few: 1.) the art of letter writing, 2.) extended family households, and 3.) the wooly mammoth.

McNally: It’s high time for the typewriter to come back into vogue, much as the turntable and albums have slowly been creeping back. I learned to type on a cast-iron Royal typewriter from the mid-1940s, a machine that’s heavy enough to kill someone with even a gentle whack to the head. I bought mine at a flea market in the 1970s when I was in grade school. My next typewriter was an electric Smith-Corona, the kind where you pop the big ribbon cartridge in and out from the side of it. A few years ago, a friend mailed to me an IBM Selectric, which sounds like a machine-gun when you type fast on it.

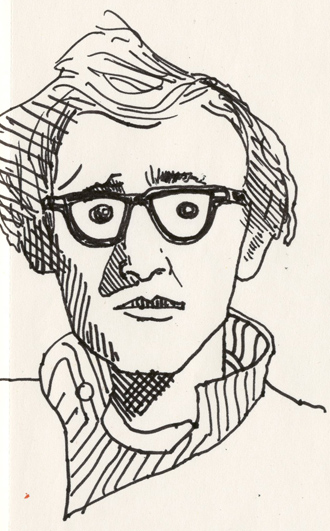

Reyn: This is more of a concept from the past (1970s and 1980s) and it’s only real in the cinematic sense: I would like to yank a dinner party out of one of Woody Allen’s movies and attend it in the present day.

Trachtenberg: The IWW. The International Workers of the World was a syndicalist movement founded in 1905 that aspired to serve as a single union for workers in every industry—mines, textiles, iron, timber, trucking. Its members were called Wobblies. Its program wasn’t just higher wages or better working conditions but a fundamental revision of the American social contract, including the abolition of wage labor. It encompassed socialists and communists and anarchists, which was part of what made it so threatening to government and business. Over the next twenty years the union was brutally suppressed. Joe Hagelund, or Joe Hill, was executed on a trumped-up murder charge in 1915; his death is commemorated in the song, “I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night.” In Everett Washington, at least five Wobblies were killed by a death squad convened by the town sheriff. At its peak the IWW had 100,000 members and could call on a good 300,000 sympathizers. By the end of the 1920s, it was down to about 10,000. At present it’s undergoing a small revival. It’s been organizing truckers in the South, for example, and there’s a chapter for employees of universities.

Trachtenberg: The IWW. The International Workers of the World was a syndicalist movement founded in 1905 that aspired to serve as a single union for workers in every industry—mines, textiles, iron, timber, trucking. Its members were called Wobblies. Its program wasn’t just higher wages or better working conditions but a fundamental revision of the American social contract, including the abolition of wage labor. It encompassed socialists and communists and anarchists, which was part of what made it so threatening to government and business. Over the next twenty years the union was brutally suppressed. Joe Hagelund, or Joe Hill, was executed on a trumped-up murder charge in 1915; his death is commemorated in the song, “I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night.” In Everett Washington, at least five Wobblies were killed by a death squad convened by the town sheriff. At its peak the IWW had 100,000 members and could call on a good 300,000 sympathizers. By the end of the 1920s, it was down to about 10,000. At present it’s undergoing a small revival. It’s been organizing truckers in the South, for example, and there’s a chapter for employees of universities.

––Why about this thing appeals to you?

Beal: While I’ve always had a kind of unfulfilled romance with cowboy living, my particular interest in chuck wagons has to do with the fact that I am returning from a week in Far West Texas by myself, where I cooked most of my meals in a cast iron skillet that I bought at a cowboy supply store (the spurs were prettier but less useful). The food tasted good, and I imagine would have tasted better eaten out of doors, under the stars with family and friends. Now, traveling eastward on a plane from El Paso, I’m contemplating my return to family life in our apartment in New York City, with two children under the age of four, where mealtime will resume its usual madness. The idea that a man would pull up in a horse and wagon, portable kitchen in tow, light a fire, make fresh food, and then my family and I would all gather round for a meal with our neighbors or fellow travelers would answer of so of our many dining issues. Also, someone else is making the coffee in the morning and doing the dishes, too.

Bock: There’s something wonderfully bizarre, something almost chastely naïve in the idea behind the automat — the future is now; just press this button and, bingo, here is your tasty roast beef sandwich on white with mayo. (I remember being a kid and my mom taking me to one and the whole event was magical, even if the food actually was kind of bland). Now, the truth is, in the present day, we know too much: to be preserved like that the bread would have to be chemical-ized to death; the meat, to be warm, would have to be kept beneath a heat lamp, or else your sandwich would be cold and wrapped in cellophane and antiseptic. But the idea of an automat itself is romantic and it’s vision of the world and of food has a certain wide-eyed charm to it. And, if you went to eat in an automat, you wouldn’t have to give your order to someone, which is always a plus.

Chenoweth: 1.) A letter feels like a present—something perfect and made just for its recipient. A letter has a nice stamp and the scratch of someone’s handwriting. 2.) I think it’s too bad that people are isolated within nuclear family units. I’d like to live with/be very near my extended family because a.) I love them and b.) they could help me with childcare. Because playing with a 10-month-old is wonderful, but it can get pretty boring. 3.) I think it’d be amazing to see a furry, 11-foot-tall, six-ton elephant.

McNally: I miss the sounds of a roomful of people typing. You know when you hear that sound that something tangible is being accomplished, as opposed to the soft-touch keypad where someone is likely Googling themselves or updating their Myspace page. What I miss about the typewriter is that its purpose was singular. The only thing to do with it is type. No surfing, no Googling, no checking Amazon rankings, no looking up old enemies to see if they’ve self-destructed. I have great memories of sitting in front of my typewriter, working on short stories. I have no memories attached to my computers, which are as disposable as a twin blade razor.

McNally: I miss the sounds of a roomful of people typing. You know when you hear that sound that something tangible is being accomplished, as opposed to the soft-touch keypad where someone is likely Googling themselves or updating their Myspace page. What I miss about the typewriter is that its purpose was singular. The only thing to do with it is type. No surfing, no Googling, no checking Amazon rankings, no looking up old enemies to see if they’ve self-destructed. I have great memories of sitting in front of my typewriter, working on short stories. I have no memories attached to my computers, which are as disposable as a twin blade razor.

Reyn: Partially, I would like to exorcise my slavish devotion to the lives depicted in those films. Even if the exchanges at these cinematic dinners (at Elaine’s or more likely in someone’s book-lined, impossibly cozy Upper West Side apartment) were often self-indulgent parodies, I would feel that I have achieved something by participating in its real, present-day incarnation. Somehow, and perhaps this is linked to my Russian soul or growing up in Queens, I somehow became convinced that if a wild-haired, bespectacled man in a V-neck sweater handed me a marked-up volume of The Collected Poetry of e.e. cummings across a food-laden table in Manhattan, it would mark me at the epicenter of intellectual life.

Trachtenberg: To begin with, the IWW is a global organization, in both senses of the word. One of the reasons the old labor movement was so ineffectual was that it defined its interests narrowly. It was organized by industry—automotive, film, etc—and its power was highly centralized, and the result was that there was little solidarity among its individual unions. Auto workers wouldn’t mobilize on behalf of miners; teamsters wouldn’t strike in solidarity with civil servants. And of course the more powerful the leadership grew, the more it became like management. In theory, at least, the IWW is an organization that recognizes the common interests of everybody who works, including the self-employed, whom the old unions excluded. What all of us have in common is that we work for our living, as opposed to invest or manipulate money—in the case of the banks and brokerage houses, money that doesn’t even belong to them. Our commodity isn’t money, it’s ourselves, our strength, our skill, our knowledge. And in a global economy in which corporations can hire those things more cheaply overseas with the push of a few buttons, all of us are in the same boat. As a writer and teacher, I’m as vulnerable as anybody who works on the line at GM.

––How do you think the present would be improved?

Beal: Instead of a lot of isolated chaos among families in separate apartments at meal time and a lot of frantic preparing of variations on salty, starchy foods and then cajoling the kids to eat, there would be mass and melded chaos among many families together. The kids who were old enough to play on their own would do so, the younger ones would have many adults to pass them around and keep an eye on them. Also, ideally the chuck wagon driver (called "Cookie") would play the guitar and sing and have a good number of tall tales to tell so there would be built in entertainment around the campfire. This sounds like a happy alternative to the whining (kids) and threatening (parents) no dessert that is our usual m.o. And then of course all mess would be on the ground and not all over the kitchen floor. The skillet would add a little iron to our diet, and the horses would have velvety noses, gentle demeanors, and sweet breaths.

Bock: Life would be a whole lot more fun if there were really high-end automats with walls of machines and all kinds of cool buttons and sliding doors, behind which awaited all sorts of yummy gourmet fast foods made with free range organic type ingredients. Major metropolitan areas already have such a high speed and level of automation — there’s a level of popish Hong Kong-style architecture to stores now where they’re basically kiosks anyway, and you get your cream puff or whatever and move along, high turnover, bing bang boom. At some moments I think the automat fits perfectly with this.

Chenoweth: 1.) We’d have keepsakes. We’d probably care more about punctuation and capitalization. And every day, around the time the mailman was due to arrive, we’d start to get happy. 2.) We’d know more about our own histories. We could have ping-pong tournaments. If I made the soup, Grandma could make the salad and Uncle Jim could set the table. 3.) We would feel awe—at the technology that brought him to life, and at the forces (climactic and otherwise) that killed him off. Maybe we’d think more about our own evolution and our own eventual extinction.

Chenoweth: 1.) We’d have keepsakes. We’d probably care more about punctuation and capitalization. And every day, around the time the mailman was due to arrive, we’d start to get happy. 2.) We’d know more about our own histories. We could have ping-pong tournaments. If I made the soup, Grandma could make the salad and Uncle Jim could set the table. 3.) We would feel awe—at the technology that brought him to life, and at the forces (climactic and otherwise) that killed him off. Maybe we’d think more about our own evolution and our own eventual extinction.

McNally: No longer would the computer be blamed for formatting problems or spelling and grammar errors, which, astonishingly, my students try to pawn off on the poor machine. Nope, it’ll all be human error, which is the actual cause of 99% of my students’ problems. No longer will I have to hear “My hard-drive crashed” or “I got the dreaded blue-screen last night, so I took my computer to IT.” The typewriter is a difficult machine to lay blame on.

A typewriter instills discipline. I used to write longhand and then type my short stories, but I would make damned sure that each draft of a story was as good as I could make it before I began typing, because the act of retyping was so laborious. The computer has made me lazy. I can be slack on the first, second, third, fourth, and fifth drafts. Also, I’ve forgotten how to spell words I used to know how to spell, because I no longer need a dictionary by my side. (In truth, I do keep a dictionary nearby, but I don’t open it nearly as much as I used to.)

If we all had to go back to the typewriter, our days would be longer and more productive, and we’d give our brains some much-needed exercise.

Reyn: Maybe these dinner parties continue to exist among certain circles, but I have yet to be invited to the perfect one of my dreams. Okay, so maybe the present would not be entirely improved, but how bad would it be to unplug ourselves from our computers, peel ourselves away from our five-disc sets of The Wire or Entourage, and instead huddle around the table for a long evening’s discussion of Kant or Ingmar Bergman or the unfathomable meaninglessness of our lives?

Trachtenberg: One, a revived IWW would have to ditch communism. If history’s taught us anything, it’s that Politburos are even worse than corporate boards. It would need to redefine what makes somebody a worker, as opposed to a boss, or recognize that some bosses really are workers, or have the same interests as workers. It would probably need to give up the rhetoric of ‘smashing’ shit. Personally, I don’t care if we keep capitalism as long as no corporate CEO makes more than 20 times what the janitor does. And a reconstituted IWW should expand its constituency to include consumers. If nothing else, that would give the union much more power. If the workers at Bank of America go out on strike, how long will it take Bank of America to find new ones? But if you can get a million Bank of America credit-card holders to hold back their payment one month, you can bring down the bank.

––What do you imagine the present-day obstacles would be?

––What do you imagine the present-day obstacles would be?

Beal: There are at least two obstacles that I can think of. The first was an obstacle back when there were chuck wagons, which is that the food probably wasn’t all that good except for maybe the sourdough biscuits. I’m guessing on a good night it was fresh killed rabbit, some bitter wild greens collected from a ditch, biscuits, and gravy. But I bet there were plenty of times that it was all about the dried buffalo meat. (A quick Web search, a day later, pulls up "son-of-a-gun stew" and "blackbird pie." I’m not encouraged.) I’m a little more hopeful about breakfast, because my chuck wagon man would have chickens in is wagon, and we all agree on bacon around here. All the same, there would likely be a cholesterol glut and a paucity of fresh fruits and vegetables. The second problem is that chuck wagons were made for cattle drives heading west, and I live a stationary life in one of the most densely populated cities in America, where, even in the old days, there were no chuck wagons, just ice men and street carts. So not only is my fantasy anachronistic, it’s totally geographically off.

Bock: I don’t know that it’s the kind of place that I’d want to go to alone, every day, on my lunch hour, if I was a temp in Midtown NYC — that might be a little too depressing and isolating. But then again, I might want to go every day and eat there and read. Why not? In fact, there’s actually a small automat running on St. Marks Place in NYC. You buy food like fries and hot dogs, and anything that needs to be heated, you put in a microwave. It’s a nice idea and an honest attempt at bringing back this concept. Having said this, I do think we know too much about health and microwaves and preservatives for the automat, at this moment, to be much besides a cool novelty, the kind of place you see and are enchanted by and spend some money at, basically, as a lark.

Chenoweth: 1.) Laziness. Email is so much easier. 2.) It would be very hard to get everyone to agree to live in one place, because someone loves the Midwest and someone else can’t more than an hour from the ocean, and just where is everyone supposed to find jobs, anyway? 3.) Where would a mammoth live? In Siberia? In a refrigerated cage? Also, I’d worry that he’d be lonely.

McNally: No one’s fingers are strong enough to make the keys of a manual typewriter work anymore. We haven’t become just a fat nation; we’ve gone weak in the fingers. Also, we’ve grown accustomed to where every machine we own, including our telephone, must have the capacity to entertain us. It’s hard to go back to the days when a machine performed only one function. We all need to go into technology-detox.

Reyn: Finding a date in one’s schedule, an apartment on the Upper West Side that is large enough to accommodate at least ten (French Chinoiserie tapestry addressed in one corner, German Expressionist horror film in another, a heated debate about Nabokov’s real-life model for Pnin around the centerpiece), finding friends who still stay up past 11pm, staying up past 11pm yourself, decent traveling weather to the dinner party, brushing up on Murnau and Nabokov, red wine and humble comfort food, elegant but comfortable evening wear.

Trachtenberg: I’d say the first obstacle is that nobody identifies as a worker any more. Everybody wants to be an “entrepreneur.” You have the most downtrodden people in this country identifying—to an absurd extent—with the super-rich. I’m talking about WalMart clerks earning less than $30,000 a year voting against a presidential candidate who says he’ll raise taxes on people who earn more than $200,000. And that’s not because the clerks don’t know math. It’s because they think that one day they’re going to make $200,000 and they’re damned if they’re going to pay taxes on it.

––How could these obstacles be overcome?

––How could these obstacles be overcome?

Beal: For the first issue, I would take up a collection among my neighbors for our chuck wagon man to do an intensive course at Chez Panisse in cooking, gardening, and foraging. We’d help him set up and tend a little garden, and we wouldn’t mind if he had to pick up a few items at the deli. For the second problem, there’s an empty lot nearby where we could make a fire and could tie up the horses. Either that or we’re just going to have to head west ourselves.

Bock: Well, nothing is wrong with an occasional lark, for one thing. For another, there’s absolutely nothing in this universe that cannot be solved by ingenuity, hard work, and a couple of hot lesbians in string bikinis making out with one another.

Chenoweth: I don’t think that any of these obstacles will be overcome. In theory they could, but they won’t. We’ll keep moving toward virtual connections, both epistolary and familial. But maybe we could design a nice home for the mammoth, and maybe we could clone him a friend.

McNally: Calisthenics for the digits? I’m not sure. Very few of my students have ever done any manual labor. Maybe we all need to do some tasks that require pliers and a hammer, something to toughen up the fingers. I’ve recently begun writing longhand again, and I’ve brought my turntable and albums, which I haven’t even looked at in over twenty years, up from my basement and dusted them all off. I spent winter break building floor-to-ceiling bookcases. Though I’m only forty-three, I’m growing increasingly tired of technology. And so, in some very small way, I’m fighting back by reclaiming those things that are disappearing from our culture. I don’t want to lose books. I don’t want to quit writing by hand. I don’t want to waste any more days reading the opinions of people who feel compelled to express them not because they have any knowledge on the subject but because they have access to the Internet. When the end of the world comes, it won’t be with a whimper; it’ll be with a cacophony of ring-tones. And how depressing will that be.

Reyn: June 4, at my friend Sonya’s apartment, Red Bull martinis and Saint-Émilion, roasted chicken and Nosferatu. Dressed in DKNY. Anybody? Anybody?

Trachtenberg: Maybe start by inculcating Americans with the reality principle. And bring back the cool black cat emblem.

Jaime Clarke is the author of the novel WE’RE SO FAMOUS, editor of DON’T YOU FORGET ABOUT ME: CONTEMPORARY WRITERS ON THE FILMS OF JOHN HUGHES, and co-founder of POST ROAD, a national literary magazine based out of New York and Boston