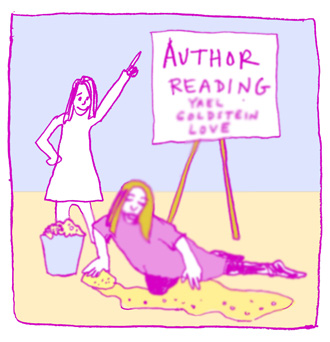

Talk Show 21: with Sven Birkerts, Lisa Gabriele, Yael Goldstein Love & Adrienne Miller

15.01.09

Sven Birkerts is the author of Readings, The Gutenberg Elegies, Reading Life: Books for the Ages, Art of Time in Memoir: Then, Again, and a memoir, My Sky Blue Trades. He is the Director of the Bennington Writing Seminars, and is the editor of Agni. He lives in Arlington, Massachusetts.

Lisa Gabriele is the author of Tempting Faith DiNapoli and the forthcoming The Almost Archer Sisters, both published by Simon and Schuster. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Salon, Nerve, Glamour, Vice, and The Washington Post. She lives in Toronto where she also directs and produces for television and radio. Visit Lisa at www.lisagabriele.com.

Yael Goldstein Love is the author of the novels Overture (Doubleday, 2007) and The Passion of Tasha Darsky (Broadway, 2008), which are actually the same novel. To make sense of this, you can visit her website at www.yaelgoldsteinlove.com.

Adrienne Miller is the author of the novel The Coast of Akron, and is the former literary editor of Esquire. She lives in New York City with her husband, and is finishing her second novel.

––Name a place and time in which you’d like to have lived.

Birkerts: The question is really, for me, which novel would I most happily pull around myself? A different answer every day, but the answers are interesting. Today I’m thinking something from Balzac, Paris in the late 19th century, or Schnitzler, Vienna in the early 20th.

Gabriele: I would love to have lived in the 1890s, in Dawson City, Yukon.

Love: Medieval Europe. Doesn’t really matter which country or which century, but I’ve got to be lower class wherever I am. No noble/monastery life for me. Preferably I’d be a drudge within a noble house, but I’d take peasant, too. This is a longstanding dream. When I was four years old my favorite game was to dress up in drab-colored, raggedy clothes, fill a bucket with water, and flood the kitchen. I called this game ‘scullery maid.’ There’s a lot of photographic evidence of this, by the way. My mother claims not to even know where I learned the term ‘scullery maid’ much less what attracted me to the role. She gets defensive whenever those pictures surface, and insists on pointing out that I never had chores as a child.

Miller: Late eighteenth-century America, probably Philadelphia.

––What about the time period attracts you?

––What about the time period attracts you?

Birkerts: What draws me is not the plumbing or the likeliness of fleas, but my fantasy of scale, of a certain immediate social density. Places big enough to support a diverse café culture, a sense of release from what Marx called “the idiocy of rural life,” though on other days said idiocy exerts its own appeals.

Gabriele: I did live in Dawson in the late 1980s, almost a hundred years after gold was first found in its hills. I fell in love with the dusty ghostness of the town, like I seem to do all mining towns, from Bisbee and Jerome, Arizona, all the way up to the North American tundra line. Love them. Not sure why. I’m not a big believer of reincarnation but there’s something about an old, nearly abandoned mining town that has always felt eerily, instantly familiar to me. But the period that most attracts me is the year or two of massive expansion, as Dawson grew from being a handful of filthy canvas tents inhabited by a handful of filthy men, to a teeming, cosmopolitan city of 40,000 people.

Love: The urgency that comes with a life so bound up with death. There was the constant threat of war, the constant threat of disease, and people didn’t turn away from this reality. They faced it head-on, made it the center of their art, thought, and even their festivities. As a result there’s something so large and awe-embracing about what they produced – their music, art, architecture, and so on. All succeeding eras seem somehow pinched in comparison.

Miller: I do appreciate that early America was largely a ruffian culture, and that the late-eighteenth-century was a time in which people blew their noses on their sleeves, lived in log cabins, ate with their fingers, and gouged out people’s eyes in tavern brawls, etc. But it was also the Enlightenment, and the central belief of the Enlightenment was that the world could be understood, that everything could be mastered and perfected through reason and rationality. It was a time that produced the most incredible geniuses ever to exist – Jefferson, Franklin, Mozart, Haydn, Rousseau, Edward Gibbon. To have heard the Jupiter Symphony when it was first performed! To have read (or at least cut apart the pages with your penknife, because that’s the way books worked then) The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire when it was first published! And, oh, to have been in the Assembly Room at Independence Hall in Philadelphia at the floor debates during that intolerably hot summer of 1776, and to have seen shy, awkward young Jefferson with his flowing red hair sitting silently and lankily, and to have witnessed elderly, avuncular Franklin piping in with another long-winded story that seemed as if it were going nowhere … but that always ended up summing up everything brilliantly and beautifully. I’m also kind of obsessed, to the point of fetishization, with the whole Neoclassical aesthetic: give me a dome, some columns, and a Chippendale chair to sit in, and that’s all it takes to make me happy.

––What do you imagine would be the best part of living then?

Birkerts: I like the idea of a genuine critical mass of alert humanity, rather than its virtual stand-in, and the sense, too, that the future is still vitally in formation and that the earth has not been colonized to within an inch of its life.

Gabriele: It would be amazing to watch how a city evolves, fast-forward. One day mail moves by horse and buggy, the next, a telephone line is installed. One day everyone lives by gas light, the next, electricity is strung up and pumped in. Mostly, how cool to be one of the few women who dare to venture north in search of personal fortune. I would have done that, as, no doubt, my options would have been limited to marrying young and moving directly from my father’s house to my husband’s. I would have read about the northern migration and fled home. I would like to think that I would have been entrepreneurial, opening a sewing shop or a restaurant or a school. But the whore’s money might have been too difficult to resist. Plus I’m a sucker for a corset and feathers.

Love: I think this whole ‘life-with-death’ mentality appeals to me primarily because I am super-duper scared of death. I’ve never managed to shake that childhood awake-in-the-dark-contemplating-mortality thing that most people manage to move past (or at least healthily suppress) in adulthood. I’m still totally bowled over – and kind of affronted – by mortality. So I think the best thing about living back then would be, basically, not being like this. Being able to look at life without the terror of death mangling my view.

Miller: I must be drawn to this era in part because of the manic revolutionary fervor in the air, and because, even then, people (OK: members of the white, male gentry, but still) seemed to have understood that they were living in a remarkable time. There seemed to have been a feeling that they were living in a precedent-creating era: they were remaking and reimagining the world. Not to sound too crotchety, but how often do we look around at this shallow, frivolous, lowest-common-denominator culture of ours––not to mention our sometimes criminal government––and feel that this is the best time ever to be alive? I mean, doesn’t every right-thinking person sort of have to believe that humanity has gone kind of gone backward? Also: late eighteenth-century clothes were super cool.

––What would be the worst?

Birkerts: The afore-mentioned fleas, still-primitive dentistry…

Gabriele: The smell. People reeked back then. One of the main pleasures of watching Deadwood was how the series accurately depicted the vile hygiene. Also bad would be the violence, especially against women. Despite my modern bravado, and all joking aside about prostitution, joining the gold rush as a woman would have been a horribly dangerous thing to do; rape was common, murder too. The overall lawlessness of an unformed society would have been stressful. But still, I’d have been game.

Love: As it turns out, I’m not actually a big fan of war and disease. I am TERRIFIED of the bubonic plague. Way more than it is reasonable to be terrified of a disease that hasn’t claimed a victim in centuries. Also, I get cold really easily and I don’t much like the heat either. In general, I’m not much of a trooper, physically speaking. And not being able to read. I find it hard to imagine life being all that enjoyable without books. Maybe if I could be a scullery maid in a monastery (did they have scullery maids?) and a big-hearted, forward-thinking monk could secretly teach me philosophy and theology and some alchemy for good measure at night. That sounds pretty appealing. But there’d still be war and disease to contend with.

Miller: Obviously, it wasn’t such a great time to be a woman. (On the upside, I would have probably gotten very good at those needlepoint alphabet primers you always see on tours of old houses.) And, boy, would it have sucked even more to be black or Native American. What else? Well, there was no anesthesia, the public hygiene was hideous, the lifespan was forty, women could almost be guaranteed an eventual death in childbirth, you were up at dawn and in bed at dusk, the last meal of the day was at 3 pm, you ate what you grew or killed, and you were pretty much entirely self-sufficient (which might not have been such a bad thing, really). There were no pharmaceutical drugs. But there was lots and lots of alcohol. But no Stephen Sondheim. And I’m firmly of the mind: If there’s no Sondheim, what’s the point?

––What bit of culture from today would you want with you?

––What bit of culture from today would you want with you?

Birkerts: Certainly not television, or the internal combustion engine, or the concept of insurance, or sleep-aids, or plastic, or the camera, or cell-phones, or the internet, or the idea of the diet…Maybe the idea of melting cheese onto grilled meat (if that had not yet been discovered)…

Gabriele: My education. I think, as a woman in the late 1890s, it would help open up my options—hopefully making prostitution an unattractive alternative. Oh, and my iPod.

Love: A few years ago my husband pointed out that if we happened to be transported back to ancient Rome (we were watching the TV series Rome at the time), we wouldn’t be able to help modernize the empire because we don’t actually know how anything in our modern world works. So we decided to each learn how something really important works, just in case. I chose ‘how to make penicillin’ and he chose ‘how to generate and harness electricity.’ Neither of us has done it yet. But I guess bringing penicillin back to medieval Europe would mess up my whole life-with-death thing, anyway. Which kind of proves how stupid my medieval fantasy is. Obviously I’d rather live in a world with penicillin than one without, and I’d rather everyone else did, too.

Miller:

1. Antibiotics

2. Dental floss

3. Pilates machines

4. iPods

5. Sondheim

6. Purell. So much Purell.