Strawberry Jamming: Darryl’s Dodger Days, Memories of a Young Fan

22.06.09

A native of Los Angeles, I recently told two New York friends that the experiential difference between these two great cities, for me, is comparable to the difference between reading the Internet (L.A.) and reading the newspaper (New York City). L.A. can be dense, yes, but generally, in L.A. you proceed directly to the thing. A bee-lined Prius spirits you to your destination swiftly as a high-speed WiFi connection loads any chosen URL. While ads and commerce may distract, if the driver—the web-surfer—is to be lured from her chosen course, she must forsake her current path/location totally before proceeding to the next. New York City reads like the Old Gray Lady for me. Here you follow any front-page story to the inside of the newspaper past myriad new points of entry. Headlines and teasers beckon you to different stories—international, local, wires—like subway stops opening up to the many pocket neighborhoods as diverse as can be. In New York you’re infinitely distracted, guided by impulse and chance (then there’s of course the New Yorker in LA in a Prius or another car––another story). Surface from the subway, cross town, happen into a bistro for a glass of rosé, or even read that rare piece on Bolivian unrest.

A native of Los Angeles, I recently told two New York friends that the experiential difference between these two great cities, for me, is comparable to the difference between reading the Internet (L.A.) and reading the newspaper (New York City). L.A. can be dense, yes, but generally, in L.A. you proceed directly to the thing. A bee-lined Prius spirits you to your destination swiftly as a high-speed WiFi connection loads any chosen URL. While ads and commerce may distract, if the driver—the web-surfer—is to be lured from her chosen course, she must forsake her current path/location totally before proceeding to the next. New York City reads like the Old Gray Lady for me. Here you follow any front-page story to the inside of the newspaper past myriad new points of entry. Headlines and teasers beckon you to different stories—international, local, wires—like subway stops opening up to the many pocket neighborhoods as diverse as can be. In New York you’re infinitely distracted, guided by impulse and chance (then there’s of course the New Yorker in LA in a Prius or another car––another story). Surface from the subway, cross town, happen into a bistro for a glass of rosé, or even read that rare piece on Bolivian unrest.

It’s an apt metaphor, I believe, because either city can drive the id totally nutzo. I wonder what Darryl Strawberry would think of this comparison. The former baseball star has spent a good deal of time in the major megalopolises of both coasts. Strawberry grew up in South Central but started his Major League career with the New York Mets—later returning West to join his hometown team, the Los Angeles Dodgers1, at just the time my youthful baseball obsession was peaking. Perhaps Darryl would appreciate the element of distraction I see as inherent in the experience of the two cities, with his history of deleterious drug and alcohol abuse, depression, and womanizing—which burgeoned during a mostly fatherless, aimless childhood and adolescence in Los Angeles, blossomed during his days in New York with the Mets, and blew his career totally back in L.A. with the Dodgers.

–––––

1. He later did a stint in San Francisco with the Giants before ending his career back in New York with the Yankees, making him the only player in MLB history to have played for all four original New York teams.

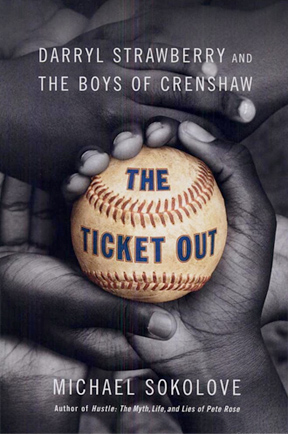

Aside from the charmingly diminutive, scrappy center fielder Brett Butler, Darryl was my first baseball hero—for the very brief period he was healthy and productive as a Dodger. It was about a month after my ninth birthday that he first started in right field for the Dodgers on opening day, 1991. Brett (also a Dodger) had this old-school charisma in his game. At 5’10”, he was baseball-short. His thick brunette coif was scorched with a decidedly un-jock-like streak of gray. Brett hit maybe two homers each year. His main contributions were defense, base-running, solid plate appearances, and all-around get-your-pants-dirty-style play. He was an excellent bunter. All about the E for Effort. Darryl, on the other hand, was your classic complete player, a natural and automatic star. A crowd-pleaser. He made it look insanely easy, yes—this was his critics’ continual hew and cry. But that was simply his grace at work. At 6’6” and over 200 lbs., he was just massive and toned, his sculpted muscles and elegant gait belied the somber notes I saw in his face. “Darryl Strawberry was beautiful. That was the first thing you noticed,” writes Michael Sokolove, who chronicled the careers of Darryl’s exceptional high school baseball team, the Crenshaw Cougars, in The Ticket Out: Darryl Strawberry and the Boys of Crenshaw. “A pure physical glory.”

Aside from the charmingly diminutive, scrappy center fielder Brett Butler, Darryl was my first baseball hero—for the very brief period he was healthy and productive as a Dodger. It was about a month after my ninth birthday that he first started in right field for the Dodgers on opening day, 1991. Brett (also a Dodger) had this old-school charisma in his game. At 5’10”, he was baseball-short. His thick brunette coif was scorched with a decidedly un-jock-like streak of gray. Brett hit maybe two homers each year. His main contributions were defense, base-running, solid plate appearances, and all-around get-your-pants-dirty-style play. He was an excellent bunter. All about the E for Effort. Darryl, on the other hand, was your classic complete player, a natural and automatic star. A crowd-pleaser. He made it look insanely easy, yes—this was his critics’ continual hew and cry. But that was simply his grace at work. At 6’6” and over 200 lbs., he was just massive and toned, his sculpted muscles and elegant gait belied the somber notes I saw in his face. “Darryl Strawberry was beautiful. That was the first thing you noticed,” writes Michael Sokolove, who chronicled the careers of Darryl’s exceptional high school baseball team, the Crenshaw Cougars, in The Ticket Out: Darryl Strawberry and the Boys of Crenshaw. “A pure physical glory.”

Loping around Dodger Stadium’s right field with those long legs, or swatting towering tape-measure homeruns over the same fence he defended, he was usually probably hung-over or on speed or both. I realized this, even at the time. My Darryl worship in the early 1990s effected all kinds of new knowledge and world wisdom in me. His extra-curricular habits were public domain, as readily available in the daily newspaper as the box score. As a kid, I read with sadness and disillusion of his cocaine habit, alcoholism, spousal abuse, and extra-marital affairs in the “C Section,” the Los Angeles Times sports pages. After just one strong season with the Dodgers in 1991, Darryl sunk to new self-destructive lows. Following a spate of injury-plagued seasons with the Dodgers, he never quite regained the greatness he had in New York. I watched as he deteriorated year by year. After leaving L.A., Darryl continued to play for the rest of the decade—eventually rounding out his career with some fairly mediocre seasons—punctuated by moments of his old glory—as part of the mid/late-nineties Yankees dynasty that won all those World Series. But in 1991, I saw Darryl’s last productive year as a young star. He was just 29 years old.

Squaring childhood sports idolatry with ugly adult realities like cocaine abuse, wife-beating, infidelity, etc., was a tricky algorithm for my young mind. It was a heavy, heady, formative experience that very much stays with me. His fall from grace and baseball stardom was timed perfectly with my own coming of age in the lunatic, Mike Davis-y Los Angeles of my childhood… Those years of the Rodney King Riots, which brought the fatigue-clad National Guard to my neighborhood, where local businessmen took to the roofs with their assault rifles to stand guard against looters. The devastating Northridge Earthquake that collapsed L.A.’s beloved freeways and chased our family from my childhood home. Santa Monica hills fires that rained down ash I brushed out of my hair and clothes. Asthma attacks from the pollution. The murder of my elementary school music instructor in a botched gang-jump robbery. Each of these events seemed to insist on one of life’s most unpleasant, necessary verities, which I first learned through Darryl’s own sad story.

*****

During Darryl’s Mets days, it was pretty much accepted: This was a future Hall of Famer at work. “The black Ted Williams” he was dubbed. In the 1980s the youthful star seemingly had it all going for him. A perennial all-star (an honor meted out to the most popular players, based on fans’ voting), he lead the Mets to the 1986 World Series Championship after just three years with the squad, and joined the exclusive “30-30” club (hitting over thirty home runs and stealing over thirty bases in the same season—a rare feat, and even rarer in pre-steroids-era baseball) the following year. I mean man he was good. He could run, hit, hit for power, field, all with the grace of a ballerina. He was a household name. And what a name, Strawberry—you already knew it.

During Darryl’s Mets days, it was pretty much accepted: This was a future Hall of Famer at work. “The black Ted Williams” he was dubbed. In the 1980s the youthful star seemingly had it all going for him. A perennial all-star (an honor meted out to the most popular players, based on fans’ voting), he lead the Mets to the 1986 World Series Championship after just three years with the squad, and joined the exclusive “30-30” club (hitting over thirty home runs and stealing over thirty bases in the same season—a rare feat, and even rarer in pre-steroids-era baseball) the following year. I mean man he was good. He could run, hit, hit for power, field, all with the grace of a ballerina. He was a household name. And what a name, Strawberry—you already knew it.

I can’t tell you how excited I was when I heard Darryl would be joining the Dodgers for the 1991 season. A hometown star, an L.A. kid, coming back to play for the home team! He had a then-characteristic great season in New York the year before, finishing third on the MVP ballot. In the off-season he inked a $22.25 million deal with the Boys in Blue for five years of play. When he signed up with the Dodgers, he was partying hard, yes, but still playing hard too, and amassing crazy offensive stats. Just off the charts. His 28 homers in 1991—not a career best, but at the time an all-time high for L.A. lefties—put him on pace with then-Homerun King Hank Aaron’s record-setting career. With 280 dingers before the age of 30, Darryl was being discussed, legitimately, as a candidate for that most hallowed and elusive of all sports records. L.A. was more than happy to have its hometown boy back, and now that he was a veteran, he was cast as the leader of a top-shelf team—along with Brett Butler there was Orel Hershiser, Eddy Murray, Mike Scioscia… with all these greats, Darryl was the cherished, newly anointed Face of the Dodgers. And the fans felt it. There were Strawberry promotional memorabilia unending, Strawberry-based promotional literature, and the continual chants of “Dar-ryl” from the right field stands (I remember thinking these sounded, at least in part, light a taunt). He was named Big Brother of the Year in California that first year. I was so personally obsessed that first season, I can still call up all Darryl’s 1991 stats by memory—28, 99, .265, 125. That’s homeruns, RBIs, batting average, strikeouts. I always kind of liked that Darryl struck out a lot. It was like the badge of a power hitter for me.

And 1991 was an exciting season in the National League. Back in the early nineties, the Atlanta Braves were still in the Western Division—there was no expansion yet and there was no Central Division, it was just East vs. West. The Braves were a real powerhouse—David Justice, Ron Gant, Terry Pendleton, “Neon” Deion Sanders, and that great pitching staff of Glavine, Smoltz, and Steve Avery. The Braves were the team to beat in the N.L. during those years, and often in the World Series. In ’91 it came down to the final games in the Western Division. Sadly the Braves beat my team in a thrilling division title race. It was still enough to get me hooked on Major League Baseball. I already loved the game—I was a little league shortstop and pitcher2—but it was in 1991 that I first came to life as a fan, learning the history and the complexities of the rules. I followed the games obsessively, rushing to finish my homework early in order to tune in for the pre-game show with Vin Scully. When the games weren’t on T.V. I’d stay up late in my room listening to the radio broadcasts. I read box scores every morning at the breakfast table, and when I went away for a week of Cub Scout camp, I had my mother save every C Section for me to read upon return. I became a fixture at a memorabilia shop I discovered out in the Valley and quickly amassed an impressive card collection my sister helped me organize into themed binders. I’ll bet a floppy red plastic folio, stuffed in a box in my parents’ garage, still holds about three pages of Darryl cards from that time. My most treasured cards (more for the photo and design than the value—I preferred the Topps of that era over Upper Deck et al) I framed in thick plastic cases.

–––––

2. I was later drafted no. 2 overall in my league, which produced a current Major Leaguer. Seriously. He had left, at that point, for a different league, but still… I’ll share that factoid publicly every chance I get.

A little boy’s relationship with his baseball hero is a weird, monkish symbiosis. You’re always dealing in concrete abstractions—stats, newspaper stories, faces. At night, I’d go to sleep thinking of Darryl’s batting stance, his signature leg-kick (more graceful can-can than grunt Canseco), his slow deliberate uncoiling into that beautiful left-handed swing (why is it that lefties always swing so pretty?). I remember staring at his face—sad, a little, but so strange and inscrutable, pictured in some of the promotional literature I received from the Dodgers. Fixed to the image, I pondered the inner workings of his mind.

A little boy’s relationship with his baseball hero is a weird, monkish symbiosis. You’re always dealing in concrete abstractions—stats, newspaper stories, faces. At night, I’d go to sleep thinking of Darryl’s batting stance, his signature leg-kick (more graceful can-can than grunt Canseco), his slow deliberate uncoiling into that beautiful left-handed swing (why is it that lefties always swing so pretty?). I remember staring at his face—sad, a little, but so strange and inscrutable, pictured in some of the promotional literature I received from the Dodgers. Fixed to the image, I pondered the inner workings of his mind.

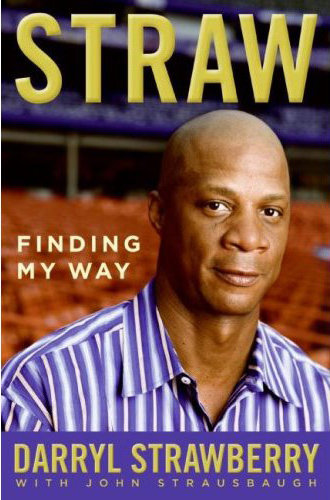

But in Sin City Darryl got headed in quite the wrong direction. As he writes in his new sports/recovery memoir, STRAW: Finding My Way, “It was in L.A. in 1991 that I was introduced to smoking crack.” In L.A. Darryl’s addictions moved in quickly after that first year with the Dodgers and, at long last, his still-young body began to buckle under the abuse. Over the ensuing seasons, headlines of Darryl’s sports heroics gave way to reports of his assault, cocaine abuse, solicitation, and tax evasion problems. He ended his career after a stretch of partial seasons and D.H.-ing for the Yankees. At the time he hung up his spikes, he had just 335 homeruns, fewer than half of Aaron’s record, which stood throughout pre-steroids-era baseball3. We learn in STRAW that L.A. was the beginning of a long stint at rock bottom for Darryl, from which he finally returned only recently.

STRAW is Darryl’s apology, and happy announcement: he’s found his life’s calling. Which isn’t playing right field for the Dodgers. It never was, we learn. “I’m at the height of my career, I’ve just signed a huge contract with the Dodgers,” he writes of the early 1990s. “I’ve come back home and everyone is overjoyed to see me, but who am I as a person? I didn’t know.” In STRAW, with much accounting for the “drugging and womanizing”—and at least as much Jesusing on the mend from those—Darryl spins the tale of his long road to being in-recovery, and finding his faith in God and good deeds. He’s now happily married, an active philanthropist who raises money for autism research through The Darryl Strawberry Foundation, volunteers for at-risk youth, and lives in Missouri. He is a part-time analyst for SportsNet New York. He’s taking it one day at a time. He’s OK, for now.

*****

Darryl was the most promising of five Strawberry children who had odds fairly stacked against them from childhood. Darryl and his siblings were raised by their mother after their abusive, alcoholic father abandoned the family when Darryl was 13. Of that brood, Darryl’s brother Michael comes out the best in STRAW. It was Mike who beat the odds and followed his dream, becoming an officer with the Los Angeles Police Department. As Darryl was hitting the skids and bending over the crackpipe at the start of the 1992 baseball season, and I was being disillusioned by him, Mike was out fighting crime in one of the more tumultuous weeks in LAPD history. Not long after opening day in April, 1992, the riots broke out at the corner of Florence and Normandie after the acquittal of four LAPD officers accused in the brutal beating of Rodney King following a high-speed pursuit. Darryl recounts in STRAW his brother’s shooting during the riots. Riding in his patrol car with a partner, Mike was shot in the head by an AK-47, only saved by his riot gear helmet. He amazingly survived with no major injuries.

–––––

3. And would stand today if somebody hadn’t jacked Barry Bonds vitamins with Swedish design steroids. I’m just saying. I’m a Dodger fan.

I remember quite clearly those disturbing days. My elementary school was at the corner of St. Andrew’s and Wilshire, the latter a main thoroughfare in Koreatown. K-town got hit hard during the riots, an ugly scene with the storeowners taking to the roofs with assault rifles to protect their businesses. On the second day of the riots, we were all pulled out of class and taken to the art room where were asked to pass the time by drawing on big sheets of craft paper. For some reason (very unlike them) my folks were late in picking me up. I sat around with Scott Key, and in crude crayon we rendered our vision of the insanity going on outside. Helicopters circling the sky, buildings on fire, National Guardsman marching in form or fighting back against looters and mobs with unlikely bazookas—the same I’d later see marching down Melrose, just blocks from my family’s house. We lived just off Western, one of the streets dominated by Korean-owned businesses. That’s about the time the men took to the roof with their assault rifles. An army-green Cougar with a rifle barrel sticking out the passenger window rolled down the cul-de-sac to the very end where our little craftsman stood. I watched from the dining room window as my father went out to speak with this improvised neighborhood watch. After that, my dad stayed at home and watered the roof to keep it from catching fire while my mother took my sister and me out to Tarzana to a nice big ranch house a friend owned. I remember spending those days out there deep in the Valley, watching (and God this seems awkwardly ironic now) Gone With the Wind on Laserdisc, wandering citrus tree-lined roads, and breathing clean air. When we came back, the gun store down Western, advertised with a brilliant gold-sequined sign that read simply “GUNS” had been looted, the lettering in the sign now tarnished permanently with soot.

*****

It would be misleading to suggest Darryl’s experience of anything is at all akin to mine, excepting perhaps that we both spent our childhoods in the Southland. Dude was a Major League phenom, rookie of the year, at roughly the same age I was probably sitting in a basement apartment in Montreal ditching my English Lit. survey, puffing on Gauloise Rouge cigarettes, and singing “Hot Corn, Cold Corn.” But I can’t cut the empathy umbilicus. I’m happy to see him doing well, in a way that doesn’t compare to any lingering affection I have for other celebrities from that era. There’s something about your first baseball hero that sticks in your craw, especially one with a tortured narrative like Darryl’s. You feel he always belongs to you. You refer to him by his first name throughout a lengthy, meandering personal essay based loosely on him. Bizarre as this is, you sometimes imagine the two of you, experiencing life in tandem.