Staring Back at Chris Marker

04.11.07

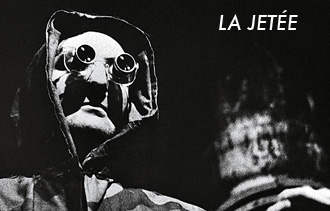

Amid the hundreds of sequential black & white photographs that comprise Chris Marker’s landmark 1963 “film”––the 28-minute La Jetée––some seven of them are given to a sequence where a man and woman stand in front of a slice of an ancient sequoia, the brief timeline of mankind represented within its rings. He is from a post-apocalyptic future, made to partake in torturous time-traveling experiment by his captors; she is a woman he recalls from one of his earliest memories, a face he once glimpsed out on the jetty at Orly when he was just a young boy. “As in a dream,” the voiceover describes, “he shows her a point beyond the tree, hears himself say ‘This is where I come from.’”

Amid the hundreds of sequential black & white photographs that comprise Chris Marker’s landmark 1963 “film”––the 28-minute La Jetée––some seven of them are given to a sequence where a man and woman stand in front of a slice of an ancient sequoia, the brief timeline of mankind represented within its rings. He is from a post-apocalyptic future, made to partake in torturous time-traveling experiment by his captors; she is a woman he recalls from one of his earliest memories, a face he once glimpsed out on the jetty at Orly when he was just a young boy. “As in a dream,” the voiceover describes, “he shows her a point beyond the tree, hears himself say ‘This is where I come from.’”

For those who don’t have an encyclopedic knowledge of film, this reference gets explained twenty years on, in Marker’s 1983 Sans Soleil, a dreamlike travelogue/personal essay that easily peregrinates between Tokyo, Africa, and Iceland. There’s a digression about San Francisco late in the film, as Marker seeks out the shooting locations for Alfred Hitchcock’s 1959 Vertigo. One location has particular resonance: Kim Novak and Jimmy Stewart are strolling through a park, when she stops in front of a sequoia slab, her gloved hand tracing out the points on her previous life. The narrator realizes that “this vertigo of space in reality stands for the vertigo of time.”

Rings with rings, points within their strata, or else outside of time. So does Marker travel. When the subject of Alfred Hitchcock comes up again (along with Marcel Proust), this time in the 1999 interactive CD-rom, Immemory, Marker meditates on the notion of imperfect memory––insane memory––and how it relates to Vertigo (not to mention Kim Novak’s character, Madeleine). In retrospect, most of Chris Marker’s work deals with that furtive functioning of our minds, both personally and collectively. As an early letter in Sans Soleil reads, “I will have spent my life trying to understand the function of remembering, which is not the opposite of forgetting, but rather its lining. We do not remember, we re-write memory much as history is re-written.”

Rings with rings, points within their strata, or else outside of time. So does Marker travel. When the subject of Alfred Hitchcock comes up again (along with Marcel Proust), this time in the 1999 interactive CD-rom, Immemory, Marker meditates on the notion of imperfect memory––insane memory––and how it relates to Vertigo (not to mention Kim Novak’s character, Madeleine). In retrospect, most of Chris Marker’s work deals with that furtive functioning of our minds, both personally and collectively. As an early letter in Sans Soleil reads, “I will have spent my life trying to understand the function of remembering, which is not the opposite of forgetting, but rather its lining. We do not remember, we re-write memory much as history is re-written.”

And in much the same way that one strains to remember certain aspects of one’s past, it has become increasingly difficult to put your hands on the films of Chris Marker. As much as La Jetée is a staple of university film theory courses, this past summer marked the film’s first appearance on DVD in North America, as well as Sans Soleil’s. That raises the number of Marker’s profound cinematic work (some 48 films in all) that are commercially available to precisely two. Curiously, a book of Chris Marker’s black & white photographs, entitled Staring Back, has emerged concurrently, culling some five decades’ worth of images that showed at Ohio State’s Wexler Center for the Arts, and more recently at the Blum Gallery in New York. A DVD and a book? This is the surest grip on the man imaginable, a rare glimpsing of a Cheshire Cat.

Marker was born Christian François Bouche-Villeneuve in Paris, his pen name taken from the Magic kind. As World War II wound down in France (Marker was a member of the resistance), he began writing jokey but pithy criticism for Esprit (one had Laurel and Hardy reading Pravda) and pieces on the likes of Laurence Olivier and House of Wax for Cahiers du cinéma. In the 50s, he traveled far and wide, making documentaries like Sunday in Peking, Letter from Siberia, Cuba Si!, and a photo book of women in Korea (all out of print) before making La Jetée.

Marker was born Christian François Bouche-Villeneuve in Paris, his pen name taken from the Magic kind. As World War II wound down in France (Marker was a member of the resistance), he began writing jokey but pithy criticism for Esprit (one had Laurel and Hardy reading Pravda) and pieces on the likes of Laurence Olivier and House of Wax for Cahiers du cinéma. In the 50s, he traveled far and wide, making documentaries like Sunday in Peking, Letter from Siberia, Cuba Si!, and a photo book of women in Korea (all out of print) before making La Jetée.

As the destinations above might suggest, Marker also deployed celluloid to document and give voice to those that were otherwise voiceless in mass media (he was also all about the owl and the pussycat, frequently injecting his favorite animals into his work). The Battle of Chile, an epic three-hour doc that captured how a democratically-elected government was bloodily overthrown by General Pinochet, depended heavily on Marker personally donating filmstock to the cause. In Staring Back, he captures both the march on the Pentagon (in 1967) and a revolutionary moment in Paris, that lovely month of May ’68.

Perhaps capture is the incorrect term to use. Most of these stills are taken from 16mm film and (when he shows pictures from the 2002 demonstrations in Paris) video. The resulting images are blurry and imprecise, as if rendered in spray paint; not crisp but indeterminate. There are portraits from all over, from every era of Marker’s career, of icons like Fidel Castro, Salvador Dali, Akira Kurowsawa, Andrei Tarkovsky (he made documentaries of the latter two directors).

These icons are shuffled in among the unknowns, from an Israeli art student to a Korean waitress, a mummy to a monk, and a group of Parisian protestors from 1961 standing in front of a newly planted tree. When filming in the marketplaces of Guinea-Bissau for Sans Soleil, Chris Marker alighted on a woman who looked at his camera for 1/24 of a second, “the length of a film frame.” It’s an eternity for Marker; she gazes back now in the Blum Gallery, amid these faces. Even in this mass of people at the political rallies and demonstrations, he sees “the everlasting face of solitude.”

These icons are shuffled in among the unknowns, from an Israeli art student to a Korean waitress, a mummy to a monk, and a group of Parisian protestors from 1961 standing in front of a newly planted tree. When filming in the marketplaces of Guinea-Bissau for Sans Soleil, Chris Marker alighted on a woman who looked at his camera for 1/24 of a second, “the length of a film frame.” It’s an eternity for Marker; she gazes back now in the Blum Gallery, amid these faces. Even in this mass of people at the political rallies and demonstrations, he sees “the everlasting face of solitude.”

Or perhaps points on a wave, fleeting human memories in the continuum of time. “The speed of the shutter stopped the rarest moment, a moment of certainty,” Marker writes in Staring Back, noting how the transitory, the unique moment, is bade to be the eternal. Yet such images are never certain, prone to be revised each and every time they get revisited. Marker trades in such perceptions across time and memory.

At the end of the gallery show, he asks us to recall that 1961 photo of demonstrators near a young sapling, at the moment right before a bloody riot with police broke out (caught in a fuzzy and frenzied series of shots). Barely noticed previously, we realize that in a picture of the new generation of protestors, the ones that convened in 2002, the same tree can now be glimpsed. In the intervening forty years between these images, which span the course of Marker’s invisible career, the tree has grown just a little.