ST. CATHERINE’S DAY

07.11.05

A grey day in Paris. Sky, Seine, streets—shades of soot.

A grey day in Paris. Sky, Seine, streets—shades of soot.

Young women stream through streets around the Opera. Colorful chapeaux atop their têtes. Canary yellow. Grass green. Brims brimming with fake flowers and ferns.

The young women pour from Paris’s legendary ateliers. House of Schiaparelli. House of Lanvin. House of Patou. It’s 1930. Patou’s popular. They parade down Rue de la Paix toward the Avenue des Champs-Elysées. Tourists photograph their hats as they pass.

The women work as seamstresses. An exhausting occupation. Poorly paid. Days spent stitching lapels, plackets, pockets. For others to wear. This day is different. The seamstresses sport hats they’ve sewn for themselves. Arm in arm in arm they march. Singing. Giggling.

“It is probably the prettiest and most characteristic sight,” wrote E.I. Robson in A Guide to French Fetes, “which Paris, in its most Paris mood, can offer to the tourist.” It’s November 25. St. Catherine’s Day.

Catherine of Alexandria died in Roman days. Executed by an Emperor she refused to wed. Milk, not blood, flowed from her wounds. It’s said.

St. Catherine became patron saint of unwed women. During the Middle Ages, St. Catherine’s Day was an obligatory observance in France. Cathedrals conducted Mass. Families feasted.

By the 18th century, Mass was no longer mandatory. St. Catherine’s Day had disappeared from the Breviary of Paris. It continued to be marked only in the countryside. With folk customs. Celebrants came in three categories. Maidens were unwed women under the age of twenty-five. Spinsters were unwed women over the age of twenty-five. The third category: Women who’d were exactly twenty-five years old. These women were called Catherinettes.

“Donnez-moi, Seigneur, un mari de bon lieu!”

“Donnez-moi, Seigneur, un mari de bon lieu!”

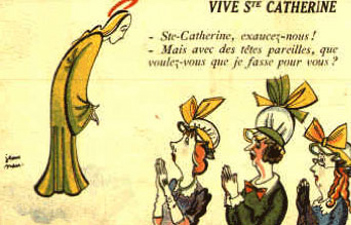

In 19th century France, St. Catherine’s Day involved sewing. Maidens dressed statues of their saint in homespun hats. Of yellow. Colour of faith. Of green. Colour of strength. Maidens prayed: “Please send me, Lord, a well-to-do husband!”

Catherinettes didn’t saw hats. They wore them. Women who’d turned twenty-five that year donned white paper bonnets. Coiffer Sainte Catherine. “To wear Catherine’s coif.” The saying has a second meaning: Left on the shelf. Unwanted.

Spinsters had their own prayer: “Un tel qu’il te plaira, Seigneur, je m’sen contente!”

“Send whatever you want, Lord; I’ll take it!”

At the start of the twentieth century, unwed women from across France flocked to Paris. To find work. Sewing. Hats. Coats. Dresses. At upscale ateliers. At downscale factories. Midinettes: the French term for seamstresses who toiled in the needle trades. Many midinettes were Catherinettes. Who carried folk customs with them.

In the 1900s, ateliers staged sham weddings on St. Catherine’s Day. Bosses “married” Catherinettes. “Brides” wore bonnets made for them by other midinettes. Bosses kissed them. Pinched them. Proclaimed them old maids. A Catherinette had this fate to look forward to: work.

By the 1920s, St. Catherine’s Day had assumed a suffragist aspect. Young, old, wed, unwed–seamstresses of all stripes made a day of it. Catherinettes stitched themselves haute hats. Top hats. Tricornes. Paraded them through Paris. Spinsters made music. Maidens chased men. Pinching them. Appalling the press. Newspapers organized races. Races, they hoped, would burn off the women’s wanton energies.

With the Second World War, the parade part of the day disappeared. St. Catherine’s Day in Paris became a festival of fashion. Milliners showed their new hat designs. Ateliers shut down. Designers staged parties. Catherinettes drank. Dined. Danced. Mingled with higher-ups. Hierarchies went out the window. The designer was a guest at his own house. A photo from the 1950s shows Lucien Lelong meeting and greeting his midinettes. Lelong looks utterly uncomfortable.

The day’s still celebrated.