So Much Beautiful Darkness: A Review of The Desert Places

30.01.14

The Desert Places

The Desert Places

by Amber Sparks and Robert Kloss

illustrated by Matt Kish

Curbside Splendor Publishing

87 pages

A couple years ago, I read Letter to a Christian Nation by Sam Harris. Early in the book, Harris describes examples of horrific acts done in medieval times. I’m still perversely struck by the mental image of an act that involved a heated drum used to force mice to burrow into the body of someone being interrogated.

From a sociological and religious view, the notion of evil can take obvious forms, as well as ironic ones (the torture described above was a punishment for religious heretics). Evil characters are pervasive in literature, from George Orwell’s Big Brother to Thomas Harris’ Hannibal Lecter. However, evil characters in books are often presented with balance: the reader is often left conflicted by the fact that the “bad” characters are not strictly bad; in other words, the characterization is not always completely black and white. In The Desert Places by Amber Sparks and Robert Kloss, we’re introduced to an evil that is wholly bad, without balance, an original creation inspired by countless mythologies and religious imagination.

The Desert Places isn’t so much a novel as it is a collage, one that gleefully and grimly explores the development and nature of evil. The ideas and definitions of badness, darkness, and horror, both as a literal and sociological construct, are as old as literature. However, Sparks and Kloss have created a work that is minimalist in its structure, yet unique and expansive in its scope. The story follows the birth and growth of an evil manifestation, a creature/person both new and composed of many historical representations. I’ve now read this work three times, and every time, I’ve discovered a passage or an idea that was lost on me during the previous readings. However, this isn’t a work that begs to explained, but rather examined.

The narration shifts from first and second points of view, and by doing so, Sparks and Kloss slyly point fingers, making the reader take the role as the creator of demonic occurrences. However, no matter how gruesome some of the prose can be, none of it is gratuitous; the writing is beautiful and fantastical, even when describing the seemingly unspeakable:

Did you build the shape of man into the rocks to know the joy of murdering him? Did you ferment the first soil with the bones and bodies of your construction? Did you stack the lands with death even before the first life? And in the hours until the first victim staggered forth from the seas, did you wander the crimson lands, peer into the halls of death and mourn the vacant corridors?

The book includes little interludes (“An Incomplete History of What Passes For Evil”) that bring historical and psychological context to the fictional, sometimes biblical implications of the described acts, deaths, and creations. In these little sub-sections, staggering ideas are put forth within the space of just a few lines:

The history of brother against brother. Set and Osiris. Cain and Abel. Polynices and Eteocles. North and South. East and West.

Wars of conquest. Wars to end wars. Wars to beget wars. The widows and orphans of wars. Bloated, blackened bodies on a bloody field. The slick and stealthy stream of propaganda.

The history, for another time, of what passes for patriotism.

The central character takes on both human and spiritual forms throughout the work, from creation to gladiator spectacles to a dancer at a party for archaeologist Howard Carter. This doesn’t make the reader wonder if the text will come to any revelatory climax; the writers carefully pick and choose examples, none of them immediately obvious, to showcase how evil takes shape and moves throughout history. There’s no obvious moralizing or cautionary messages: the reader can reflect on historical events that define evil and human frailty on their own. This isn’t a road map or a spooky imagining of reality, but a fictional wandering through the whole of history and storytelling.

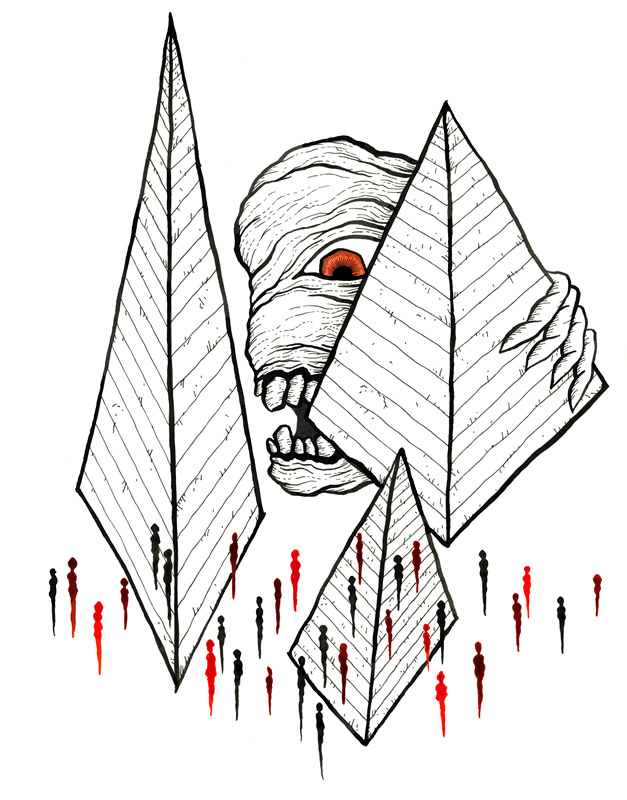

The Desert Places is a wonderful collaboration. There’s no need to try and determine where Sparks’ words end and Kloss’ begins (or vice versa). The passages are seamless and progress to the point that one becomes consumed in the progression, not stopping to wonder who has created a given paragraph. Matt Kish’s illustrations are perfect accompaniments. They are a meticulous blend of skulls, organs, and graphic representations of the given chapters. The images are literal, yet Kish made me imagine expansions of the words, and therefore imagine further descriptions of the evil.

This illustration is inspired by the Howard Carter chapter. Kish has combined his terrifying interpretation of the character with a beautiful symmetry among the slender human figures and the pyramids. He lets the creature take over the imagination (as well as its place within the text), but the subtle, beautiful details are just as vivid. His colors are limited to white, black, and red, yet he uses them in a careful balance to create these evocative drawings.

Taking this further, his art does what Sparks and Kloss do with their story: the reader is not a passive consumer of the horror, but is thrust into and even takes a subconscious part in it.

With this imaginative way of forcing the reader to reconsider evil, the publication of The Desert Places feels somehow overlooked, to me. Individually, both writers could have created singular, unique works with the same atmosphere. But combined, and with the addition of these flawless illustrations, The Desert Places becomes an even more important work, one that terrifies, inspires, and breaks ground for fictional experimentation in a time when far too many people are wrongly bemoaning the death of literary ingenuity.