“SHORT STORIES WERE ALWAYS POWERFUL AND SHARP”: AN INTERVIEW WITH AMIE BARRODALE

05.07.16

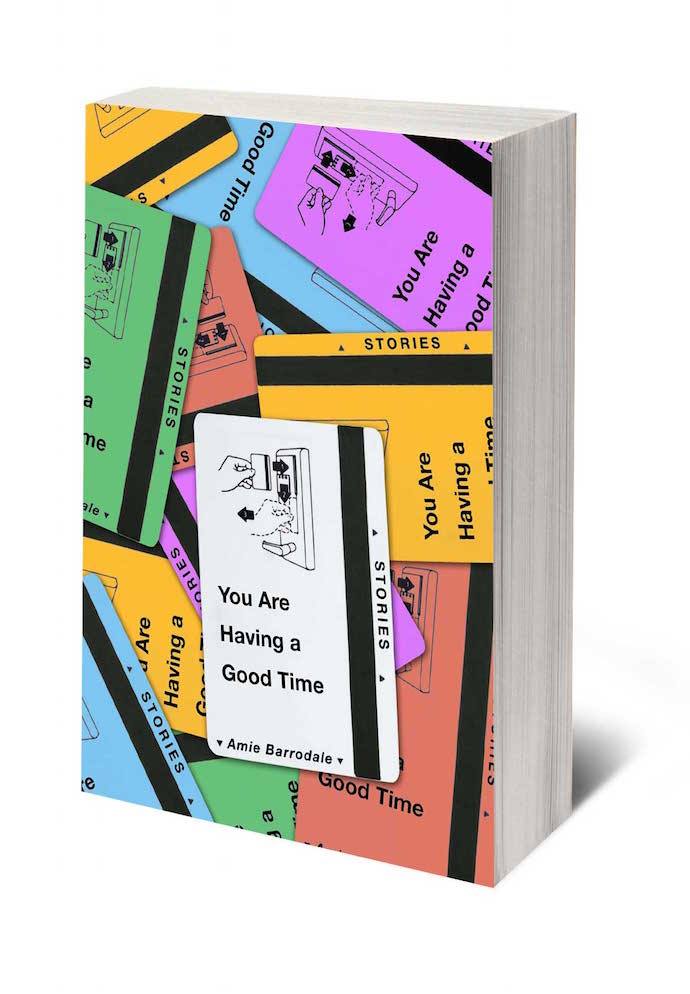

Amie Barrodale has written one of my favorite story collections. I rarely say such a thing because I don’t have many favorite story collections. Most collections I pick-up, skip around, dismiss stories because of first sentences, length, or title, but You Are Having a Good Time I read from start-to-finish. I’m not sure how she did it (well, I kind of know, there a few tricks/moves she shows), but the cohesive flow is incredible. The stories themselves are very funny, minimal, detached, and display the short story in a way I have recently come to greatly admire – as a clean, piercing, and vicious art form.

The author herself has always seemed a bit of a mystery. As a former editor at The Onion, she is currently the fiction editor at VICE who keeps a nearly non-existent social media presence. She’s a Buddhist who lives in Kansas City with the author Clancy Martin. She has a guru. She agreed to this interview only if it was through email. She likes to hide.

I emailed Amie before the publication of her debut collection – from my home in Albany and her home in Kansas City – and she responded to each question quickly, resulting in the following conversation.

You Are Having a Good Time is cohesive, balanced, and has a really good flow. I feel like many story collections just don’t gel, or they make you want to skip around, but YAHAGT is so smooth. I noted a few moves to achieve this (like how Victor tells Libby in the story “Animals” to read “The Imp” and the next story in your book is “The Imp”) but could you talk a little about putting the book together?

That’s good to hear. I can’t read it straight through, so while I did try to make it that way – I tried to order the stories in a way that felt right, and I spent some time thinking about it – I almost can’t believe it. For me, some of it’s hard to read still, like listening to yourself on a tape recorder.

But the stories were all written in this particular way, and I don’t think I want to write that way anymore, where I would go a few months without writing, and then get angry or upset enough to see something through. So if there’s something cohesive there I guess it’s a temperamental person. I don’t know if I should say that or not.

How do you want to write now?

I feel like this is a dangerous thing to admit, though it used to really irritate me when writers were evasive about it in interviews. I have always written about my life in my fiction, sometimes quite a lot and sometimes just as a starting point. I guess for the next thing I write, I’d like to be in foreign territory and make it feel real. That’s what I want to do.

These stories are about how people communicate, or how we miscommunication, so it makes sense. When your characters do connect it’s often striking. For example, when Dr. Sheppard calls Kitty and Debbie “cunts” at the end. Or what the narrator in “The Imp” does to his wife at the end. There’s like these strange connections that are made from some dark place, where before these characters tried to be polite, educated, and mannered. Ema, what she says at the closing, in “Night Report,” is another example.

Praise kind of makes me clam up. I once interviewed Whit Stillman, and he never answered my questions. This went on for years. I sent him the questions, followed up, and he kept saying the answers were coming. He is a very good person and a great writer and director, I think. But he seemed like he just couldn’t bring himself to answer the questions or tell me no. A few years went by, and I wanted to maybe try again when a new movie of his came out, and he suggested we go back to those old questions. He still had them in his email, I think. And then we did it again, where he just couldn’t answer them, and he finally said something like, “It makes it hard when you’re so nice.” Something to that effect – meaning the praise made him clam up, not that I was a nice person.

But I was a very bad interviewer, on the subject of miscommunication. I alienated that one documentary filmmaker who did the great movies about dating, Sherman’s March. He actually got angry with me. My editor was like, “I don’t mind, I just want to know how you managed that.” It may be a good idea to change these names. Another time I had a writer who called me screaming. And I was a bit young, so I just hollered back, as though I was a teenager talking to a parent. I don’t know. I always meant to write a story about this one particular interview catastrophe, but it’s hard for me to capture in writing what a disaster it was. You need full conversations, and it’s a bit subtle, to portray a disastrous conversation. You know? You can do a fight, or something, but a long disaster is tricky because it’s under the surface.

I like this Joy Williams quote concerning what a short story should contain: “A clean surface with much disturbance below.” I think you do that. How do you do that? And you do write about personal disasters. I’m thinking of the last story in the collection, “Rinpoche,” which I think is about your Buddhism guru and the death of your mother’s friend. It’s hard not to praise these stories because I like them very much. We could talk about Buddhism, or maybe your studies of Buddhism juxtaposed against modern technology, which is a really cool thing you have going in the stories as well.

I guess I spend time polishing the language, and I try to be clear about events. I try to keep things simple. I cut things a lot. I tend sometimes to have difficulty following longer sentences, maybe to a fault, so I try to keep my sentences short and crisp, as much as I can. Maybe to a fault.

I don’t think we should talk about Buddhism. It would be embarrassing.

Okay, no Buddhism talk. But I can see a really useful connection, not just in how to live, but how to write. You know, being clear headed, concise, aware of how each sentence functions, simple and direct. Last year I was into image-heavy stuff, long sentences, abstractions to a high degree. I like “precise and uncomplicated” now. I also think it allows for more humor. Are there writers or artists who you admire that do this well?

See, that’s why it can be embarrassing to talk about Buddhism, because I agree all those qualities would be very useful, but then I’m not sure that they exist. I think maybe it just gets messier and messier, and more and more complicated, if you are really aware.

When I was working on the story “William Wei,” I recognized that the language was giving me trouble, so I decided to make it as simple as it could be and still work, just so I wouldn’t trip myself up.

One time someone asked a great Buddhist teacher a question. He or she said something like, “As I meditate more, my mind becomes clearer, and my thoughts diminish. What do you think of that?” The Buddhist teacher kind of smiled and said, “Ask that again in a year.”

Anyway, I like my husband’s (editor’s note: Clancy Martin) writing. I like his novel How to Sell and his novella Bad Sex. Dennis Johnson comes to mind, though he does a lot with language, and I’m sure you’ve read him. I love Annie Baker’s Vermont Plays, and Alejandro Zambra. Tanizaki is good. I can try to think of other names. For a while I admired Kesha’s writing. This was around 2010. Her songs made me feel a little crazy, but I thought the lyrics were strong.

That’s interesting (being mindful leading to complications), In “Night Report,” Sloane Newman says to Ema, “Babe, it’s why we chant. We chant each morning. May my confusion dawn as wisdom.” But all the meditation and “being present” doesn’t work for Ema. She has anxiety and only feels better after she says she wants to shoot up the place, including shooting a blind woman.

Did your husband read these stories when you were working on them? I was recently reading a Jane Bowles biography and when Paul read her novel he said, “You make me out to be an idiot,” and she just laughed.

I think wanting it to “work” is the problem for Ema. She doesn’t know what to do with heartbreak. She is trying to “fix” it. Sloane Newam, of course, is doing the same, giving her the dharma rap. Neither of them feels quite safe experiencing, say, anxiety. Ema has to run away literally. I have the same problem. I can’t bear for somebody to see that I’m nervous. If I am a little nervous, it’s okay, I’ll let it show, but if I get really nervous I have to run away. I used to hide it with alcohol, then prescription pills. Now I just hide literally. But I hope one day to be like my friend Jody, and another friend Renata, both of whom are willing to tremble in front of people.

He reads the stories all the time. He helps me with them when I get stuck. We read each other’s work that way. I think early on in our marriage, sometimes what I wrote hurt him. Now it’s not that way. I wrote a story recently about our dog, and he was in it, and I think we were both relieved afterwards when, to my surprise, our relationship seemed stable. I mean, put plainly, we’re totally in love and he’s my best friend and the best thing that’s happened to me, but sometimes when I put something that happened between us during an extreme moment in black and white we would both be startled by it. But that’s kind of how it is, we both know, to write, so it’s okay. I’m kind of a hypocrite actually, because he once began a story and showed it to me, and I got really upset about it, and he hasn’t exactly written about us since. Except I think the hero of his novel is a bit based on me – the way she talks.

Do you have a favorite story in the collection? Does Clancy?

I think I like “William Wei” and “The Commission,” and I think Clancy likes “Catholic.” I have a soft spot for “Mynahs,” though it was always eluding me a little bit. I just like that Donald character so much. If I had to pick one, “William Wei” is the best story, I think. I spent the longest on it, and I had good help from the editor, Lorin Stein. He’s a genius at editing.

The funny thing about “William Wei” is that it was supposed to be the opening to another story, the story I really wanted to tell. I started working on it in maybe 2007. For four years I would open what was going to be my novel, and start again with that story, before getting to what I wanted to tell. But I’d choke. So I just ended up reading and re-reading this story that didn’t matter as much to me as what came next. Then I was coming up with all these ways to make the “next up” part (which became a short story, “Catholic”) more palatable. Because I felt it was disgusting, the material – just embarrassing and gross. So I was thinking, “Well I’ll put it in China,” or whatever. In short, I had abandoned it, and I was living with my mom in Seattle, and I was using OKCupid, but mostly just looking for like-minded people (writers) who wanted to waste time emailing each other. Well, in short, I never really met people, but I had a friend I met on there. I sent what became “William Wei” to him – we shared work – and he said it was his favorite of the stories he’d seen. So it was just because of him, and I can’t even remember his name now, that I ended up ever publishing either of those stories.

“William Wei” is really interesting in how the language, that voice, worms into the reader. It’s very clear and precise, but something about the narration kind of twists and turns from sentence to sentence. You kind of keep getting close as a reader, then you push away, then you try and look closer. The ending to “The Commission” is my favorite closing in the book. What made Lorin Stein’s edits so helpful?

Thank you. I like that closing. I like how that customer, Gerry, is at cross purposes, trying to apologize, but then getting carried away, and trying to upset her.

Lorin noticed that halfway through the story, once William Wei is rejected, the voice got too bare. It was like a shema. It was flat. He pointed out that in the beginning, the narrator was warm and funny, but then halfway through he just went dead. Also, there were a couple things in the story that I kept cutting and putting back, because they scared me. Lorin didn’t have them in front of him, but he recognized that they were missing, almost using psychic ability, and asked me to put them back. (Of course, I don’t think he’s psychic, I just mean he’s an exceptionally good reader, to recognize something has been cut.)

I wonder if cutting and putting stuff back, just continuing to do so, is connected to what you said earlier about Ema “wanting to make it work.” Like, you just keep trying to force the work, but maybe it’s easier when you aren’t trying to work so hard.

I think once something is right, I know to leave it alone. It isn’t like I rewrite sentences. I don’t do that anymore. I don’t know what to say, really. That’s probably true. I guess when the words aren’t coming to me in the right way, I force it. I heard Marilynne Robinson said she didn’t write for twenty years out of fear of writing a false novel. I’m not that confident.

I’ve actually never read Marilynne Robinson. Not sure why. Twenty years is a long time. Do you ever fear writing? Do you think a novel requires accessing another level of confidence compared to writing a short story?

Housekeeping is good. My husband won’t see past her idiosyncratic language, but you kind of have to, if that style isn’t yours. It’s such a powerful book. It actually scared me.

Yeah, I have trouble opening a novel. A short story I don’t mind just seeing what happens, but a novel, I get scared. I notice this in peers of mine. They kind of dick around if it’s going to be a novel. That’s one particular strength my husband has. He’s just fearless about hitting the ground running in a scene. Some non-writers don’t appreciate it, I have noticed. But every writer I know who reads him can see how strong it is. I guess I also always liked short stories better, though. I seem to remember in the 90s, no one said they were inferior. And I remember feeling like novels tended to be baggy and pointless often, but short stories were always powerful and sharp.

A friend of mine once said reading a writer’s short stories compared to their novels is like watching someone jogging around a track and not actually racing. I thought that was funny, because I was really into novels at the time. But in the past year I’ve only been interested in the short story. It’s such a sinister form that, to me, always feels like “attack mode.” So, we can expect more stories from you in the future?

Oh, good. I thought you were going to trot out that “marathon as opposed to sprint” thing. I like what your friend says. I don’t know what I’ll write next. Right now, I’m working with Clancy adapting his novella Bad Sex as a screenplay. I’m thinking about a novel, and sort of casually researching it. I think I’ll write more stories, probably, too, as they come.

———————

Amie Barrodale’s You Are Having a Good Time will be published by FSG on July 5, 2016.