Sex and Micro Prose: A Common Pornography by Kevin Sampsell and Man’s Companions by Joanna Ruocco

14.04.10

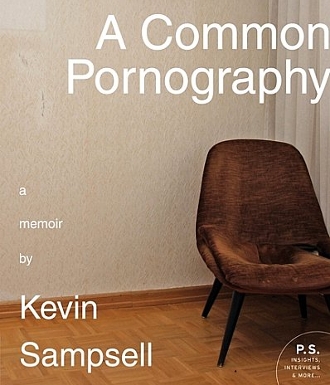

A Common Pornography

A Common Pornography

Kevin Sampsell

Harper Perennial

256 p.

Man’s Companions

Joanna Ruocco

Tarpalinsky Press

144 p.

–––––––

Although we associate short prose with short fiction, A Common Pornography by Kevin Sampsell is a memoir triggered by the death of the author’s father and recounted through miniature scenes from his upbringing. As the title implies, the book details teenage forays into pornography, using porn as a lens through which the author tracks how his father, a troubling figure to say the least, informed his burgeoning sexual desires. Sampsell humorously milks the nauseating but true idea that parents inform our sexuality. He connects the dots between his love of rock music, his early sibling and masculine rivalries, his realizations about the peculiarities of his family, and his first uncomfortable encounters with sex. All of these are awkward but awesome topics and the book is permeated with a punk rock self-assurance pockmarked by teen nerdiness.

Sampsell’s dad’s violent outbursts color many initial short chapters, some of which are only a half-page long. The book’s opening chapter/story, “Washington Street,” sets the tone: “Dad came home and went straight upstairs to the bedroom I shared with my older brother, Matt. ‘I’m going to throw everything into the middle of the street,’ he yelled.” Sampsell doesn’t dwell on scenes like this that might seem intended to elicit sympathy and instead uses this violence to illustrate the power each of his six siblings mustered up (over the twenty or so years the book spans) to leave an unpleasant household. Not all of them remain functional, but they all try. The triumph achieved by ditching abusive situations becomes a motif throughout his narratives.

During these moments Sampsell is spot on and his prose is seamless.

In “Spirits,” he describes how fantasy became his mental escape, pitting dissimilar fantasies against each other to unite their message: “At night, in our bedroom, Matt and I would talk about what our spirits were going to do next, and discuss maybe killing off some of our old spirits for new ones…” After showing how this spiritual awakening relates to their passion for Saturday morning wrestling on TV, Sampsell ends on a note that would, out of this context, feel non-sequitur: “That’s when Matt and I began reading books about Bigfoot.” Yet here, after several chapters about male violence, it is easy to comprehend protective solace taken in the idea of a salty wrestlers or giant forest beasts.

Conversely, tales of his siblings confronting life’s hard reality make one feel proud and a little empowered to know that children can sense wrongdoing from miles away. In “Fights,” Sampsell writes about his father: “There were fists thrown, choke holds, objects broken.” But as the kids get older, they begin to fight violence with violence: “…there was a time when Matt got fed up with the fights and decided to do something. He stepped between [mom and dad] and pressed dad against the wall… ‘You’re not going to talk to Mom like that. You’re not going to hit her again.” What reader can resist cheering for such a courageous young boy? The wrestling match fantasy becomes real as the boys become men.

The visceral strength of some chapters is what makes others feel comparatively shrimpy. Chapters like “Korea,” “Tackle Football” or “Echo” tell simple anecdotes of boys playing sports, pulling pranks and cooking up lame schemes, and these don’t pull the weight that the heavies do. The strongest chapters are when Sampsell keeps a tight focus on the narrower narrative view, in which family scenes show how sex and sex fantasies go awry. This is much more engaging and taps into a deeper, more universal humanity. Even pieces that are micro in length, like one of the best in the book, “Vibrator,” say so much in five sentences. I quote the whole piece:

The visceral strength of some chapters is what makes others feel comparatively shrimpy. Chapters like “Korea,” “Tackle Football” or “Echo” tell simple anecdotes of boys playing sports, pulling pranks and cooking up lame schemes, and these don’t pull the weight that the heavies do. The strongest chapters are when Sampsell keeps a tight focus on the narrower narrative view, in which family scenes show how sex and sex fantasies go awry. This is much more engaging and taps into a deeper, more universal humanity. Even pieces that are micro in length, like one of the best in the book, “Vibrator,” say so much in five sentences. I quote the whole piece:

Dad gave me a vibrator once. Sort of oval-shaped. He gave it to me so he could wrap it and give it to Mom as a birthday present. Later, they kept it in a drawer by the bed. Then, shortly after, they slept in separate beds.

While I adored many of Sampsell’s poignant episodes, I felt myself at moments flipping through the pages almost too quickly, sifting for gems through a few weaker strays. Some later, more sexually explicit chapters come as welcome relief. “Cruising,” about Sampsell’s first experience with a prostitute, and “Making the Band,” about his first time at an orgy, offer juicy, mirage-like tidbits in the sometimes bleak, dry desert of his described youth. Single sentences here and there glow too: “Heavy breathing is the same in every language.” So true! Then again, maybe every scene can’t be brilliant. Maybe all this to say that by showing his textual muscle Sampsell becomes his own stiffest competition.

On that same note, Joanna Ruocco’s second book, Man’s Companions, succeeds and suffers with some astonishingly heartfelt and surreal moments versus some flatter, overly cerebral. Each story in this short fiction collection is named for an animal — real or imagined — connoting possible pets or at least active relationships between humans and animals. Part of what compelled me to read Man’s Companions was my curiosity about a fellow author who had also pondered “Unicorns.” This story, I happily report, is one of the highlights of the book. In it, an embittered writer ruminates on writer’s block, while processing jealousy of her prolific boyfriend by reducing his success to ‘phallogocentrism.’ “When I am not writing, I feel bad. But when I am writing, I am usually not writing. I feel bad. I sit in front of the computer doing small, surreptitious things to my body. When Dave is writing, his…posture is excellent and his fingers never stop moving across the keyboard…” She arrives at the phallus via noting Dave’s confidence, his efficient practice, and his boarding school education. “Whimsy,” she writes, “is how the phallogocentric artists try to hide the phallus. They hide the phallus right there in the open, with unicorns.” Even in this passage, one notices Ruocco’s peculiar writing style, in which short sentences show logical ideas leading to the next in almost robotic bursts. Then they leap somewhere else completely, recalling Lydia Davis’s grammatical, poetic math.

This prose style works mostly in Ruocco’s favor. “Flying Monkeys” features two women, the narrator and her row mate, Margaret, an intimate apparel saleswoman, on an airplane discussing topics that all boil down to dating and sex. “Margaret leans on the tray. We have one of those greasy windows so everything outside seems thicker. Maybe what’s inside seems thicker too, but you can’t look inside from outside unless you’re one of those flying monkeys, those weird guys, from Oz. It’s all kind of sexual.” The story, told entirely through dialogue, offers strange conversations, some of which barely make sense and employ absurd metaphor and punctuation.

‘I am down to my last frayed nerve,’ says Margaret. ‘It’s you-know-where. It’s in my you-know-what.’

‘Your fanny flower?’ I say. ‘Your fifi? That’s what happened to your French tips? You’re like, clam-digging?’ Margaret cannot impress me.

‘I date Europeans?’ I say. ‘I boffed this leathered Hollander? On Stage? In Holland?’

While not all of Ruocco’s stories are so insistent on covering feminine territory, the ones that have the most natural rhythm definitely are about women’s relationships and their anxieties about men. “Snake,” my favorite piece, stars the narrator and her best friend, Janie, on a desert road trip. The narrative slips between dream and reality, as the narrator drifts in and out of sleep to reveal her thoughts on the surly men she finds attractive, a clear-skinned snake in which she can see organs squirming around, and her memories of growing up with Janie.

I remembered she had an easy-bake oven and she was afraid to get it dirty so we never baked in it one time. We watched it like a TV. If we had an easy-bake over, we could grow our babies in there. We could order sperm from a catalogue, or solicit contributions from well-built, literary homosexuals and mix a little baby cake. It would grow lean and light in the easy-bake over, and we’d just wait around for the timer to ding. Ding!

Again, metaphors for the phallus abound. In this arena, Joanna Ruocco’s voice is witty and confident. Sentences stand out all over. “She has the Arc de Triomphe of teeth,” notes the narrator about a woman in a dentist’s office in “Ugly Ducks.” “Her smile emits this soft wattage,” goes the narrator in “White Horses.” I prefer these honest, eloquent observations to the puzzling syntax Ruocco sometimes gets into, which hides characters’ emotional outbursts.

As a writer of short fiction, people often ask me whether flash fiction invites a wider, shorter attention-spanned reading audience in and I can’t say that it does. Nor can I say that micro prose benefits from the pop entertainment appeal of tiny, paragraph-long chapters despite the best hopes of experimental writers with an eye on a wider readership. But as with any narrative form, an idea or a story sometimes calls for brevity and the structures of both of these books validate the short forms of the pieces inside, each of them offers a quick-flow, highly rewarding, whirlwind read.

Buy A Common Pornography from Powells

Man’s Companions at Tarpaulin Sky

________________________________________________________

Related Articles from The Fanzine: