Seen Through To: Radiohead’s “True Love Waits”

19.05.16

I can’t think of an analogue. Imagine it, for a second: imagine writing a hauntingly pretty song, the sort of sing-along pop/love song that would, for most acts, serve first as an album–and then as a concert-closer for years and years, the sort of song most bands would love to basically wrap themselves around, one of few poles by which a band is known. Imagine having written a song that could and would function like that, and then imagine not recording a studio version of it, and releasing a version that your producer eventually calls “that shitty live version,” and playing the song only itinerantly for two decades. Imagine all that. And then, finally, imagine recording it. Would be sweet, right? You’d finally be like yes, this is how it should sound! We’ve lived with this song for so long we can sing it as easy as we can our own names!

Except now imagine you’re Radiohead.

++

“True Love Waits” was first played in 1995 and you can hear the supposedly first airing of it right here:

I can’t find metrics, but one has to imagine that song—the audio ripped from that video—constituted one of the most downloaded tracks through Napster in its early years; certainly that’s how my friends and I found it. We loved it I think basically immediately; like lots of earlier Radiohead stuff, there was a sweetness to this (a sweetness I’d argue that’s seeped from the band’s stuff, but that’s neither here nor there).

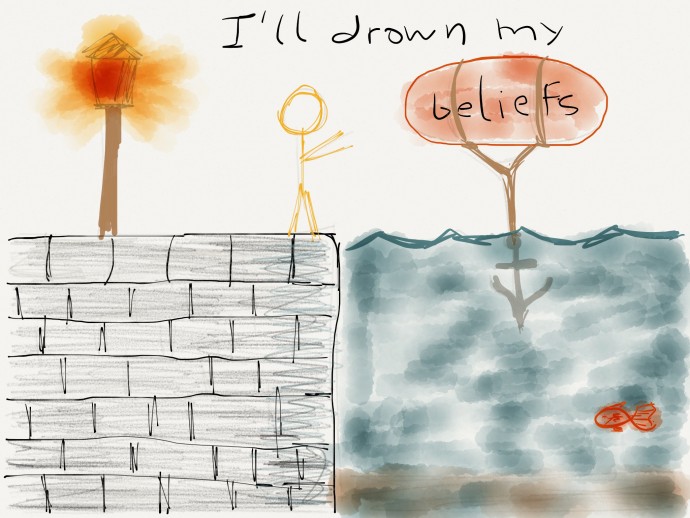

For a write-up of the song itself, I invite you to head elsewhere: you can find out how the line “True love waits on lollipops and crisps” was supposedly inspired by a story Thom Yorke read about a kid who’d been left in an attic and forced to subsist on a diet of junkfood while his parents vacationed for a week, and you can find how the first lines in the song—about the speaker drowning his beliefs to have your baby—speak to the shift from childish to adult love, from selfish what’s-in-it-for-me affection to that firmer, messier sort marked by what-can-I-do-for-you.

But the song doesn’t need explication, and Radiohead needs nothing else said about them by now. Here’s what the song sounds like now (this, anyway, is what the piano sounds like, which is one of only very few instruments used in the song; at present, there’s no online version of the actual thing):

++

There’s a line that comes up in Jorie Graham’s work, but it’s the phrase I now associate heavily with all of her work, and with lots of art I end up liking just in general. I usually remember the phrase having come up in her perfect book Never, but I’m wrong: it’s actually there in “San Sepolcro,” the first poem in her second book, Erosion. The phrase is “seen through to.” The context:

In this blue light

I can take you there,

snow having made me

a world of bone

seen through to.

In its full surroundings it doesn’t hang quite as it does in my skull, where it’s been lodged now ten years. Seen through to. There’s something guiding in the phrasing, something leading. I come back to this phrase more often than I’d admit (at least weekly), and I find something spookily keen in it. Let’s just stipulate that what we’re seeking when we’re consuming art is some vision offered, shared (this’ll all be a gross oversimplification, as is requisite). Let’s further stipulate that one of the saddest experiences re: art is when we come across art is essentially inert, less unchallenging than unpursued.

Perhaps you’ve had the experience my wife and I did two nights back: we watched a movie on Netflix we’d heard positve stuff about from people we trusted, but then the movie turned out not to be bad as much as it was infinitely empty. Bland. As if a movie that took its creater’s first ideas and didn’t pursue them in any way, just assumed that ‘good enough’ meant ‘good.’ Unpushed. A Hollywood friend sometimes describes such premises or jokes as being First-Meeting jokes or premises, meaning they’re the sort of thing you think of right off the top of your head, and are funny, but not really engagingly so. They’re what you’re used to, and so are comfortable and somewhat comforting, but almost by definition can’t really be much lasting. Which is nightmare territory, because at least with bad art you can countenance it, recoil, move elsewhere, but with good-enough art all you can do is sorta stomach it: it’s not bad enough to regret, but not good enough to make you happy you consumed it. The analog to eating works well: if you eat poisonous food, you can puke it up, but if you eat blah, empty calories (bag after bag of those ridiculously white hot dog buns made entirely of enriched bleached flour), all you’re doing it taking your stomach’s space.

This is where the phrase seen through to, for me, exists. The stuff that’s most resonant is stuff that feels like it’s been tended. This doesn’t mean fussed: a good rock and roll song needs just as much seeing-through-to as some tender ballad. The point is, there’s something I’d argue almost religious about art that’s been pushed to be all it can become, has been pushed all the way. Art that’s been asked of; art that risks asking something of us.

++

For the record, neither my record-store-working friend nor I can think of a band who’s done anything like it, can think of zero examples of bands who’ve had a song they’ve played live for twenty years and have, finally, after two decades, recorded a studio version of the song in a way that’s radically different from the original version, radically different from all previous recognized versions.

Because just listen to this new version. Those four (piano?) notes that start the song, how they work their way down. The skeletonized quiet through which Yorke looses his still-so-sweet keening. It’s just about the same key as the original version; the chords are still all there; the song moves in the same way. It’s precisely the same song, in important ways, yet what Radiohead’s done seems the equivalent of stripping nine layers of paint off finished moulding. The gears have been exposed. What originally was a phenomenally sweet love song has been rendered somehow both steelier and infinitely more fragile. What originally was a song by younger men about devotional love has been cast in starker spookiness by middle-aged men who presumably have, twenty years on, a much firmer grasp on the realities True Love demands of us.

I’m not arguing that Radiohead’s Still An Important Band or that You Should Love Them, any of that. Their new album, A Moon Shaped Pool, is useful to me, but I’m old now, and those here’s-why-you-should-whatever are young people skirmishes. But what Radiohead’s just done with “True Love Waits” hasn’t, to my ears, been done before, by any band in rock’s history: they waited two decades to record a studio version of a song that’s long been an audience favorite, and then recorded a studio version radically different from what the audience has heard all these years, from what the audience certainly was expecting. I’m not arguing all bands should consider following this path, nor all artists (Yeats is probably the best example, in writing, of someone who so obsessively messed with stuff, who so ceaselessly saw-through-to he’d revise poems he did in his 20s decades later), but in the rush and incessancy of what constitutes contemporary music (its making, its consumption), what Radiohead’s just done needs to be noted. Needs to be considered, reckoned with. Their raw grip on a vision. A sort of ferocious devotion. Their belief in trying again and again and again. On finding. I can’t imagine how any of us could be worse off by experiencing more art that’s been this seen through to.