Seeking Past: An Interview with Jake Syersak

03.01.19

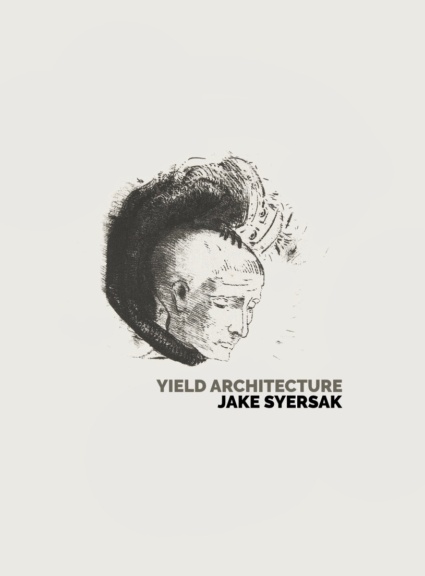

When I first got Jake Syersak’s new book Yield Architecture I flipped around in it at random, eventually coming to rest on page 72, a page that only contains the sentence “& how many warplanes are named after birds?” Above and below those warring birds is white, empty space, hovering, waiting. Reading that line of Syersak’s made me think about the question posed, sure–Nighthawk, Lone Eagle, Pelican, Talon and Osprey, among others–but it also caused me to contemplate poetic intent and surface level understanding and meaning versus something more involved than that. Yield Architecture is a poetry collection filled with densely condensed lines and prose blocks of language and yet it’s also a volume that, like our lone “& how many warplanes are named after birds?” line, situates rather than declaims.

The stridency in the book is less in the (black words on white pages) language than in the potentialities that said language (invisible beige and green ink fading in and out of focus before word and page finally seem both wholly compatible and incompatible unto any scope of readerly comprehension) enacts, could enact. In an interview last year Syersak asserted that “Looking back, I actually think now that [Yield Architecture] was my attempt to purge the influence of LANGUAGE poetry from my own poetics. My poems will always be haunted by their influence, but I hope it endures as some centrifuge of sabotage, maybe through the formless material… that manifests through sensation.”

Maybe that’s what I’m trying to get at it. I don’t know. I do know that the longer I read Yield Architecture the less sure I was what I wanted (or could want) out of a poem or capital P Poetry. And I do know that that’s what I desire out of a poetry collection–to continually have my expectations overthrown, undermined. In an interview that spanned 3+ months, with both interviewer and interviewee persevering through moves across the country, I asked Syersak about poetic success, the cross-pollination aspect of literary translation and how and why cultural and linguistic vacuums are myths, among other topics.

Both short and long-term, what does success look like for you as a poet? And what’s the happiest you’ve ever been made by the art of writing poetry? The saddest, angriest or most despondent?

Man, that’s a tougher question to answer than I anticipated. Partly because it’s so hard to dissociate the term “success” from some sort of ladder-climbing. And partly because success as a poet, for me, has always been trying to use poetry as a ladder from which to try and look beyond that sort of ideology. I’m thinking about how deeply intertwined my interest in poetry was and continues to be in conversation with the ilk of radical politics and anti-capitalist perspectives.

But I’m also thinking about how lucky I was from the start to have been mentored by some truly wonderful humans (Mark Scroggins, Eric Baus, Joshua Marie Wilkinson, Farid Matuk, Susan Briante, to name just a few) who taught me, directly or indirectly, in their own ways, that poetry only exists where there’s a community giving it oxygen–running journals and presses and reading series, writing reviews, translating work from another language, reaching out, etc.. It means a lot to me if I can gain the trust of others in a community like that. I’m well aware this might come off as gushy, overly sentimental, or at worst, naive. Who cares. We need more of that. More grating optimism. More harsh utopian enthusiasm. Especially in darker times. I once heard Susan Briante say something like, the problem with poets is that historically they’re so ready and willing to envision and write apocalypse but hardly willing to write utopia, whatever that is. The beginning of success in poetry on the page is seeing it off the page, maybe. I want to believe that’s true.

Of course, I’d also like to be making at least poverty-level wages, something I’ve been unable to do as a working student for at least the last 6 years or so. I just got done working my annual summer job, which barely keeps me afloat: prepping and painting the exterior of houses in the godawful humid summer Georgia heat for 60+hours/week. I’m made exhausted, sad, angry and despondent more from poverty than anything to do with poetry.

This debacle at The Nation—as a publishing poet, one whose work seem to be the opposite in every single way from that poem published by The Nation’s editors, I’m curious what you think. If poems like that are being published in the U.S.’s most well-known poetry-featuring magazines, does it ever discourage you in anyway? Do you concern yourself at all with submitting poems to old east-coast powerhouses like The New Yorker or The Atlantic Monthly or The Nation or is that not to your interest at all? Does it depend on different factors?

Speaking of things that make me angry, and on a related note to my response to the last question, I will say this: I’m not one to tear down other poets, but I’ve personally gotten into heated arguments in the past, on various platforms, to keep Anders Carlson-Wee, and others like him, off the page. And that was for his ritualistic carnivalization of poor, rural, and/or working-class people in what he himself has openly equated to celebrating “primitivism” in the past. Unfortunately, he’s one node in a much larger network of poets I’ve noticed over the years doing so. Fortunately, however, most people who actually do come from the aforementioned backgrounds see through his facade. Even more fortunately, if they don’t, he and people like him, if given the right platform, will inevitably embarrass themselves in even worse ways, as is the case right now–which is why I’m not discouraged by it in the least. I’ve heard people say they’re scared his books will see a spike in sales now on account of the controversy, but I think any person willing to pick up a book of poems is curious enough that they will eventually see what’s really going on.

Though I’ve never really concerned myself with submitting to magazines like that. It’s been a while since I’ve picked up a copy of The Nation, but I know The Atlantic Monthly and The New Yorker still often publish poems embedded in unrelated prose articles, as though they’re second-rate, best dismissed, or, worse, seen as ornamental. One is much, much better off looking taking a look at literary journals whose editors work tirelessly–for no compensation–to curate folios of incredible contemporary writing (often from writers of otherwise marginalized backgrounds): Black Warrior Review, Asymptote, Denver Quarterly, Colorado Review, Puerto del Sol, Court Green, Deluge, Dreginald, Seedings, etc. I’m more concerned with placing my work in the hands of editors I trust and who consistently contribute to making poetry better on and off the page than I am chasing illusory professional merit.

In your poem “Appendix Nailed to the Bathroom Stall Wall of Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain & Addressed to Kenneth Goldsmith” you have Duchamp saying, “I have forced myself to contradict myself in order to avoid conforming to my tastes.” Could you contextualize this quote within your own life? Are there poets you love that readers of Yield Architecture would be surprised by? Musicians, artists, lifestyles, occupations, anything—what are some of the major contradictions in your life that have made you into the person and writer you are?

Well, if as you said my work looks like the absolute opposite of Carlson-Wee’s (and thank god), it’s because it is intentionally so. I was just talking to a friend the other day, who also grew up in a very small town, about how our work doesn’t really indulge or reflect that past. Sometimes you work therapeutically through something head-on and sometimes you work through something, if not by seeing past, seeking past it. Yield Architecture is largely antithetical to large swathes of my life. But it’s got residues all over it. It’s riddled with contradictions, from the title to the epigraph (one of my favorite lines ever, by Rainer Maria Rilke: “& in the vast you vastly yield yourself”) to the pretentious high art references to the cringe-worthy little confessions. I’m really interested in surprises, arresting paradoxes, and contradictions that hold physical and mental spaces together like glue, maybe to a fault (ha!). A funny moment comes to mind all of the sudden: while I was studying in Tucson, the poet Rafael E. Gonzalez, after reading some of my poems (of the more far-reaching variety), turned to me and said, “shit, you’re more Catholic than I am, Mr. Atheist.” What can I say, the glue is really appealing sometimes.

All that said, Yield Architecture is, implicitly, a map of escape-routes from what I viewed as some of the limitations growing up; at least, I’ve come to see it that way now. Some of the more obvious influences of mine are name-dropped explicitly or quoted from in the book itself. It’s hard to say from my perspective what would or wouldn’t surprise people. I can remember reading a lot of Anne Sexton, Gertrude Stein, Kim Hyesoon, Paul Celan, Gerard Manley Hopkins, and Basho while writing it. I’m kind of always re-reading Alexander Pope and Percy Shelley. I suppose some of those will be surprising and some of them won’t. I remember listening to a lot of what I might call anachronistic-sounding music while writing the book: Califone, AJJ, The Tallest Man on Earth, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Mount Eerie, Son House–folky-minded old and new stuff that blends old and new and raw and cooked sounds out of place and time. It may or may not surprise people to learn that after writing Yield Architecture, I’ve cultivated an interest in ecologically-conscious theoretical work of the Speculative Realist variety, especially Object-Oriented Ontology. I’m increasingly obsessed with Maghrebian literature. I don’t know. I once worked at a county fair at the bingo tables and I was a preschool teacher for 2 years. I once lived in the nouveau-riche hellscape of a south Florida town for a year. I watch a weird amount of mumblecore indies and little feel-good romantic comedies to unwind, despite pretty much hating both genres. For some reason I love watching movies I genuinely hate. This question is taking me into too weird an introspective place and I’m going to stop now.

Early in Yield Architecture you write:

architecture, dear architecture,

a friend writes, “the home is for screaming or no emotion”

& I’ve been an envelope of that for years now. how a paper plane

ignores engineering

& takes flight anyway

what am I supposed to do with that? What am I, supposed to that?

what am I, supposed?

Reading that I immediately thought two things: 1) through and through, the speaker of this poem is a hopeless romantic; and 2) the speaker of this poem, heartless, doesn’t have a romantic bone in their body. Viz-a-viz the book being “riddled with contradictions,” you allude to this above somewhat, but for me as a reader the whole of the text is an alluring undercutting. To be didactic, when I felt myself on solid ground in the book that ground suddenly turned into quicksand, then water, then mushy concrete. Is resolution a word that you find yourself interested in as a poet? Do you like endings more or beginnings? Or is it all in medias res all the time?

Haha, well, I am “formally” trained, above all else, as a Romantics scholar, so that reaction doesn’t really surprise me. Nor does your reading of that being “undercut,” confused, or challenged, since my other major interest is the historical avant-garde, or, what keeps the artistic avant-garde churning in the cement-mixer, so to speak. I wrote the majority of Yield Architecture in my final year of my MFA at the University of Arizona, mostly from recyclings and fragments of stuff I had accumulated for the previous 3 years or so. The more I look back on the book, the more it reads to me, simply, as someone just very self-consciously trying to figure out how to write a book of poems–not just how to write a poem with a capital “P,” mind you, but trying to configure its coordinates amongst a gigantic history of “The Arts.” It’s a simultaneously audacious/arrogant and beautiful thing, romantic and contra-romantic, to assert the right to throw your hat into that ring, isn’t it?

But yes, I definitely wrote Yield Architecture with an arc in mind, in the context you’re speaking to. That is to say, it wasn’t just compiled out of disparate chapters. I think of it more as a long poem. The “mushy concrete” feeling at the end is pretty apt, as I think the book becomes messier as it progresses, and if it comes to any “resolution,” it’s just that: let’s run through the concrete, before it seals itself off from us, for good. Let’s look for interobjective chance, opportunities to make imprints that, if not felt, at least leave some residue of trying to be felt. There’s no real resolution to be had in trying to stomp out the footprints of tradition; it just becomes another step. I guess what I’m trying to say is that I don’t really consider resolution possible in a book of poems. In that sense, I’d say I hate beginnings and endings equally. In the arts, they seem a little artificial to me. That’s probably why the book is so referential. There are seams everywhere–some tighter, some looser. The vacuum is a myth.

You translate the work of other writers a lot. Can you A) share one of these translations; B) share why, out of all the non-English poems, poets and poetries out there, you choose to translate it; and C) give some generalized or specific notion on your own conception of translation? Do you attempt to get as close as possible to the original or is (small or large) veering not only inevitable but needed? Does it (obviously) depend on the poet/poem/language? Thoughts?

Unfortunately, copyright law prevents me from sharing whatever I want, whenever I want, without specific permission. But some of my translations from of Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine are available online. I’m also beginning a translation of the poet Hawad’s selected poems (my translations, in fact, are translations from his wife’s translations from the Tuareg language into French). Both authors are from postcolonial francophone North African countries. I began familiarizing myself with largely untranslated authors of this region a few years ago when it was becoming increasingly clear how much momentum Trump and white supremacist organizations were gaining traction. Like a lot of us, I felt increasingly helpless, and trying to work through those matters in the medium of poetry seemed increasingly tedious. Let me be clear: I don’t necessarily believe that’s true. But for me, personally, at the time, it was seeming so. As a white poet, I felt I could only do so much through my own original work, so I increasingly turned, and am continuing to turn, to translation to try and elevate other voices.

Both Hawad and Khaïr-Eddine are particularly interesting to me because they both work from a politically-charged Surrealist aesthetic similar to that of Aimé Césaire, taking advantage of Surrealism’s “universal” language to strike out at their colonizers. Both Hawad and Khaïr-Eddine developed particular aesthetic techniques as means in this endeavor. Khaïr-Eddine developed what he coined a “guerrilla linguistic,” in which a violent, volatile, syntax-wrenching, iconoclastic poetry is deployed with the intention of warping the colonizer’s language in such a way that reveals its dominion in speech and culture and re-presents it, as an affront, to the colonizer. Particular sounds, slangs, or double-meanings become weaponized. Hawad deploys something similar with his “furygraphy,” a term combining “fury” and “calligraphy,” designed to generate a poetry of long-but-elegant, bizarre stylistic repetitions that foment space in his poems and, alongside it, increasingly more static illumination.

But to answer your question, yes, getting close or far away from the authors is heavily dependent upon the context. In translating non-Anglo-European authors, a firm rule of mine, especially if working with authors of a colonized region, is that their cultural allusions remain in-tact and are not domesticated. I want the reader to be affronted by the foreign. I’m not going to invite someone to share their world only to tell them it needs to look more like mine. That would defeat the most revolutionary act of translation, which I take to be the cross-pollination of ideas and, moreover, cultural approaches to said ideas.

Darn. As a non-translator for the most part, I find that all pretty amazing, especially “I’m not going to invite someone to share their world only to tell them it needs to look more like mine.” 100%.

Let’s just end with something completely different. First thought, best thought:

Favorite sensation:

Under a warm blanket in a cold room

Favorite turn of phrase:

“Gotta nuke somethin’”

Favorite love story:

Hiroshima Mon Amour

Favorite enemy:

Toss up between Richard III, Satan from Paradise Lost, and Evil/the Deadites from Evil Dead

Favorite thing to forget:

Social media passwords

Finally and most importantly:

Anything’s anything and we all die alone

Most important thing to forget:

Anything’s anything and we all die alone