Seared Into Memory: An Interview with Molly Brodak

08.12.16

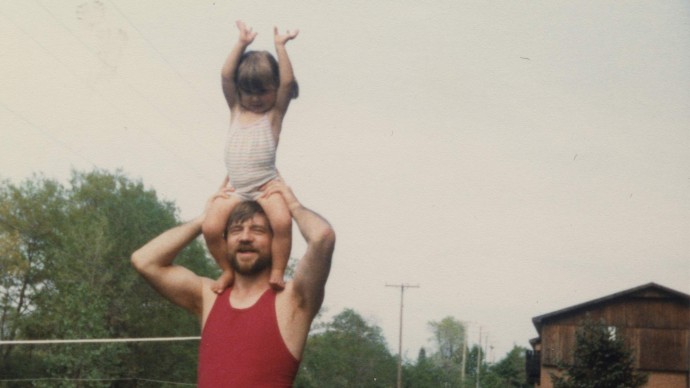

Molly Brodak’s memoir Bandit is the story of her father, the bank robber, as much as it isn’t.

Beneath the headline-grabbing tale of her father’s crimes, it is really an examination of a family shaken off a broken foundation, a fight against stories, and a search for the truth. The blood of it, though, is Brodak’s. She weaves a life out of so many disparate threads, building a whole, beautiful, unfinished thing.

I spoke to Brodak mostly about Bandit, and a little bit about cake.

JAIME FOUNTAINE: One of the first things I thought while reading Bandit was that you write about being a child very well, the strangeness and terror of things, the unearned confidence. But you also write about looking through your old journals and not remembering or recognizing things. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve often find myself asking relatives about myself as a child, not always trusting my memory. Since you said that you did a lot of this initial writing in secret, I’m really curious about the the process of trying to write about your past self accurately.

MOLLY BRODAK: Looking back now as an adult, it seems to me that childhood is a very difficult space, probably for everyone. So much is expected of you, to learn and behave and be patient all while living in this very rapidly growing body that you often can’t control very well. And you have almost no control over your life. I tried to get back into that space with a neutral mind, by looking at my childhood diaries, photos, drawings, and artifacts, and I ended up with much more empathy for my childhood self. No one ever really knows you, even the ones closest to you like family, but in honest reflection you have a chance to get to know yourself and that’s very reassuring. And, one of the magic tricks of memory is that it works in conjunction with emotion, so emotionally-charged experiences will be seared into memory deeply, which is always useful to memoirists since our most intense memories tend to be the most interesting ones to write about anyway.

I was having a conversation with a friend over the weekend about how we both felt like we spent our 20’s acting as if our childhoods hadn’t really affected us, but now that we’re in our 30’s, there’s a value in looking at what happened when you were young, and what coping mechanisms you developed to get through, and whether those are things we can lean on for the rest of our lives. I guess this is a very long-winded way of getting around to asking you what it was like to to spread your life out in front of you the way you have in this book, making connections without drawing any broad conclusions?

There’s no other way to say it but the cliched way: it’s very hard. I actively fought against reducing and narrativizing the complexity of life into this book package, but at the end of the day it is a book package, and it is reductive. On one hand it’s really liberating, very freeing, to finally put these inchoate experiences into words and get to claim my life, but on the other hand the finality of it is terrifying. Like, now I can hand someone this book and just say, ‘here it is, here is my crazy life.’ That’s wrong, you know. But there it is.

The broad conclusion of this book is that broad conclusions are useless to dealing with human nature. We are so irrational, mercurial, iridescent. I don’t think it’s just my dad who is hard to pin down. I think we all are.

I think that active fight against a broader conclusion is one of the things that sets your story apart from so many other memoirs. A lot of them are written to memorialize or apologize or aggrandize the writer’s life or the period of time the memoir focuses on. Yours seems exceptionally personal because you aren’t writing yourself as a character, but as a whole, complicated person whose life so far couldn’t be tied up in neat resolution. Did you start out trying to write the story that way?

Yeah, thank you, I’m really glad to hear when people see this in the book because I was definitely going for that. I did start writing it exactly like that. I encountered a ton of resistance from my editor over this issue, though. She saw what I was doing in resisting classical narrative structures and tropes as not intentional but as bumbling, like I just didn’t know what I was doing and she could help me correct it. Her editing put a lot of intense pressure on the book, which definitely made it better, but it was a very, very hard process. Along the way, I started to question everything about the book, even about my life at times, but the fact that the book came out of the editing process with a strong stance against turning real people into characters and real situations into plot points shows that it must have been very important to me to fight for these features.

How did your background in poetry influence the way you wrote this book?

It helped in some ways and hurt in other ways. I’m used to being elliptical and condensing language as much as possible, so when I first started writing I would write a short paragraph and be like, “there, done. Chapter five,” or whatever. I had a hard time learning how to flesh out my points and keep my a long, complex scene or idea going. I think you can still see me struggling with that in the book, which I’m fine with. On the other hand, I could use my skills in managing imagery to evoke concepts or sentiments quickly. I could focus on the language of my sentences and be patient about word choice.

I saw those shorter sections as a great way to write about memory as an uneven thing. The way a person can remember the exact smell of a laundry detergent their grandmother used in the 1980s, while forgetting most of fourth grade.

That’s really interesting, I like that! Memory is a very uneven thing. Those very specific little flashes of moments or sensory input, those are my favorite parts of memoirs. They are gold.

When you wrote about your sister in the present-tense, she’s someone of whom you are very protective, but you write that weren’t very close as children and didn’t always live together growing up. What was it like to write about your relationship with her? Did you consult her a lot? Did you fact check?

When you wrote about your sister in the present-tense, she’s someone of whom you are very protective, but you write that weren’t very close as children and didn’t always live together growing up. What was it like to write about your relationship with her? Did you consult her a lot? Did you fact check?

This question really gets to my heart. I do feel very protective of her, because I believe she bore a heavier weight than I did as a child (since she lived with Dad and I didn’t), and I saw that firsthand. It’s funny how writing about my parents felt no-holds-barred, like since they were the responsible people in our lives I could hold them accountable and just lay out their lives for all to see without hesitation. But writing about my sister’s life was different. I consulted her carefully in the beginning to make sure she was ok with what I was writing. And I grew closer to her in talking about Dad. But there were certain things she didn’t want to talk about, and I had to be sensitive to that. I feel a kind of survivor’s guilt when I think about my sister, and the feeling is very raw and I’m not sure it will ever go away. Her life was deeply, deeply messed up by our dad, and it took a long time for her to feel secure and healthy again, so writing about her was precarious and charged with a lot of emotion for me.

Siblings, maybe even more than parents, can be such important people to us, maybe the most important people. You witness together. You learn to navigate the adult world together. You can’t get that kind of permanent closeness even in a friend.

That’s so true. And I think if you’ve experienced some difficulty in your childhood, it’s nice to have someone who you don’t have to explain it to. You captured the effect of your father’s actions on your sister in a way that I think does her real justice and doesn’t say too much. You don’t make her an object of pity, and you don’t try to speak for her.

Thank you. She’s got her own story to tell, really. Every single person has her story to tell, and it is valid and valuable. I can’t tell you how many people wrote to me or came up to me to talk to me about their stories. People are just bursting with the urge to make sense of their lives. It’s humbling and wonderful and if one memoir about deep dark family history can make even one other person feel emboldened to tell her story, that’s worth everything.

Have you been getting a lot of weird hugs? The kind that people give you because they wish they could have saved you from your childhood, even though you’re fine now? (I am very familiar with these hugs.)

Ha! Yes I have a had a few from friends who’ve read the book, which are nice. I’m not a big hugger in general, so I think I give off a ‘don’t hug me’ vibe that tends to ward off stranger or acquaintance hugs.

You say that writing about your parents was “no-holds barred,” but I think you were very generous with your father, and sympathetic to your mother. There’s a real value in understanding the people that shaped you, even if they went about doing it in the wrong ways. The chapter on your mom is really beautiful and kind and rational about mental health stuff. I feel like there isn’t enough writing like that on the subject. What made you decide to dedicate a section of the book to her story?

I wanted to make sure this didn’t turn into a biography of my criminal father, which could have been an easy trap to fall into because his story is so interesting. Equally interesting to me is that such an intelligent, creative, and sensitive person such as my mom could get sucked into his manipulations. So it was really important to touch on her story too, for balance, but also because she deserved to be written about.

I think you do a good job of laying out her hardships without making it into a “cause and effect” situation. And I think that’s another thing that sets your approach apart from a lot of memoir writing. You’re not saying, “My mom had mental health issues, and that’s how it was so easy for my dad to deceive her about his first family” or “my dad robbed some banks, so I tried my hand at shoplifting.”

You wrote about the headspace of your shoplifting phase very similarly to how you described recovering from your brain surgery. They’re very different experiences that you reacted to differently, but the element of disassociation is similar. Was that intentional?

I struggled to explain to my editor why I really wanted the brain surgery section in there. She–and some other readers too–felt like it didn’t belong there. Part of why I wanted it there was just to show the weirdness of that day when my dad drove 6 hours down to West Virginia where I was living to visit me when I was recovering. That day visit was so awkward and kind of horrible for both of us, and I wanted that to be part of the story.

But you’re right, part of it was also about dissociation. I knew if I wanted to write this memoir in the best possible way I was going to have to have courage to say the embarrassing and hard things that some might scrub from their memoirs. I had to consider the idea that I have some of my dad’s sociopathic tendencies in how I dissociate from situations and from others. I had to “go there,” as it were, although I think in toying with the idea I came away with a comforting sense that I am not, in fact, like him. But yeah, having brain surgery and feeling a complete disconnect from one’s head to one’s body is a lot like the kind of hyperfocus and complete loss of self, which I consider close to the radical self-negation concept muga in zen Buddhism, is what can make you a successful shoplifter. It’s a scary place though, and I’m glad I don’t go there anymore for this petty criminal purpose. I go there for writing, or art, or baking instead.

Speaking of baking, you make some astonishing cakes. You are making these elaborate, beautiful things, just to be eaten. What kind of a process is developing recipes for you? Is it similar to your writing process? Is it an escape?

Writing recipes is like writing computer code. It’s a great challenge, because you essentially give up the code to anyone willing to run it, and if you’ve done a good enough job writing the code the outcome should be consistent and wonderful. I’m drawn to challenges, and to hands-on work that will balance my thinky writer’s life. Baking is not so much of an escape as it is reconnecting with this other part of me that needs to make and build and do physical labor.

Another connection I made between the shoplifting and brain surgery sections was in the way you spoke about having a “self.” You really distilled the process of how a person becomes and presents herself to the world in a way that’s very honest and matter-of-fact.

I think we are taught to believe in innate personalities, but I think a big part of being is choosing one’s self. Borders between what you are and what you aren’t are constantly redrawn. I find that encouraging, really.

You wrote, “The layers of my feelings toward him seem to have no conclusion…” and included a letter from your father, explaining his motivations for the bank robberies. What made you decide to do that? How much, if anything, do you believe?

I put his letter last because I wanted to give him a chance to speak for himself, as it were, in the book. I thought that would be fair. Generally I think we humans overestimate each other in our ability to articulate our motives. We expect people should be able to answer the question “why did you do this?,” but it seems obvious to me that we hardly know ourselves what motivates us most of the time. Some of it is subconscious, unknown. Some of it is a feeling we might not want to admit to. So the explanations offered are usually not very useful. I think you can see that in my dad’s explanations.

In chapter 72, you wrote about going to a Valentine’s Day party with your sister and your boyfriend, that you were “embarrassed by my happiness.” This is such a beautiful scene. It really captures a feeling that I don’t often know how to put words to, that effortless joy that sneaks in like light through the cracks. In a different kind of memoir, that scene would have been the close of the book. What made you include that scene, which feels very unlike so much of the book?

I just wanted, first and foremost, to show everyone I’m ok now, and my sister is ok now too. That’s a typical memoir move but it needed to be done, because it’s true–we came out from our weird/horrible childhoods ok. Like most people. Also I just wanted to thank my friends by showing the reader how wonderful they are, how kind and generous and forgiving and interesting. They are my family here in Atlanta, and I love them.