Sarkozy’s Soap Operetta: Eight Months in Office With the French President

12.01.08

“Imbécile!” Nicolas Sarkozy, France’s President, muttered as he removed his mic and walked out on an interview with CBS’s Leslie Stahl. The name calling (presumably addressed at his press secretary) was in reaction to Miss Stall’s inquiry into the separation rumors surrounding him and his wife, Cécilia.

The “60 Minutes” interview aired on October 28, just ten days after an official announcement in France declared the Sarkozy divorce. For many Americans, this was their first look at France’s President, an image that contrasted sharply with the stoic Jacques Chirac, Sarkozy’s predecessor, publicly denouncing the invasion of Iraq in 2001. Sarkozy’s outburst and angry candor was more Bush-esque than Chiracian and may have gone a long way to bolster France’s dusty, snobbish image in America. It went a long way, too, to bolster his own image in America, a country he openly adores (he spent his August vacations in New Hampshire). In one fell, seemingly candid swoop, he made a greater splash in the American media bucket than the Beckhams could before moving to LA.

Mr. Sarkozy has often been accused of close, influential ties with media moguls like Martin Bouygues, who he counts as “one of his best friends.” Mr. Bouygues owns TF1, France’s CBS, NBC, or ABC equivalent. In a study put out on December 4th by France’s National Audiovisual Institute that spanned July, August, and September, Mr. Sarkozy was found to be the most broadcasted personality on the news. He was most commonly seen on TF1.

Back in France, the news of divorce received greater attention, even in a public eye that has historically looked past the private lives of their leaders, such as François Mitterand, who secretly kept a mistress while in office. Even after she bore the President’s daughter, the public remained quiet. Nobody sought reconciliation through an impeachment hearing and a detailed account of his sexual exploits under oath.

Back in France, the news of divorce received greater attention, even in a public eye that has historically looked past the private lives of their leaders, such as François Mitterand, who secretly kept a mistress while in office. Even after she bore the President’s daughter, the public remained quiet. Nobody sought reconciliation through an impeachment hearing and a detailed account of his sexual exploits under oath.

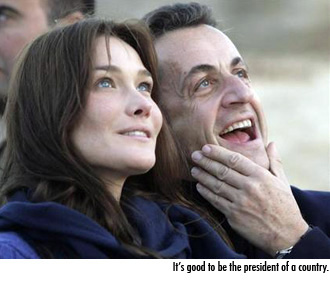

But Sarkozy is the first French president to divorce in office, and, at 52 years old, he is very much available. He wasted little time in proving his virility, appearing openly at a Christmas Parade in Disneyland Paris hand in hand with Italian model/singer Carla Bruni. During the week between Christmas and the New Year, Vincent Bolloré, Sarkozy’s billionaire buddy, flew the pair to Egypt on his private jet. The vacation afforded wonderful photo ops, and Mr. Sarkozy continues to grace the cover of France’s most prestigious tabloid weeklies, like Gala and Paris Match, consistently.

On January 8, at the annual press conference that marks the President’s return to the Elysée, Sarkozy appeared refreshed and almost eager to answer questions about his new relationship. “With Carla, it’s serious,” he declared, but he denied marriage rumors, hinting that “there’s a strong chance you’ll hear about it after it’s already happened.” Miss Bruni, however, donned two new rings, each from Dior and each worth about 19,000 Euros.

The divorce distraction came at an optimal time: amidst a swelling social unrest among a population at the brink of economic reform. Sarkozy was elected on promises of reforming the anachronistic French economy, home of the 35-hour work week and excessive social handouts. His slogan, “work more to earn more,” promised to make overtime hours accessible to workers and almost tax free to employers. But the legislature proved to be as confusing as the French bureaucracy itself, and the 35-hour work week didn’t budge. Prices, however, did, and the French saw their buying power diminishing.

Sarkozy’s answer was a raise, for himself. On October 30, he requested a 140% raise, which was approved by the National Assembly and put his monthly earnings at 18,690 Euros, up from 8,000 Euros. He wanted to be making a comparative salary with that of his homologues. François Fillon, his Prime Minister, nets 20,000 Euros a month.

On November 6, Nicolas Sarkozy celebrated six months as France’s president elect, dining on lobster bisque and lamb, face à face with Mr. and Mrs. Bush in the White House. The trip marked the first official visit to Washington by a French president since Jacques Chirac came in 2001 in the wake of 9/11. He spent the next day at Mount Vernon, wooing the American Congress to a dozen standing ovations.

But back at home, social tensions had risen over Sarkozy’s first really controversial reform: social security. France faces a similar problem as the United States: who will pay for the retirement of the Baby Boom generation? Part of Sarkozy’s solution is to target the régimes spéciaux, professions like railway workers, opera singers, and members of the military who, because of the particular hardships of their jobs, are granted early retirement plans and other benefits. Some professions have been exempted since the early 1800’s. Sarkozy’s plan is to raise the number of years they are required to work before taking full advantage of retirement from 37.5 to 40, which would help pay for the increasing number of retirees. The private sector underwent the same reform in 1993.

It is estimated that the government will need to come up with an additional 20 billion Euros by 2020 to compensate for the increasing number of retirees, and the reforms are overdue. In 1995, France’s Prime Minister, Alain Juppé, attempted the same reform, unsuccessfully. A nationwide strike broke out, paralyzing public transportation in France for three weeks until Mr. Juppé rescinded the reform. This is often the pattern in France: reform followed by strike followed by a return to the status quo.

“There will be strikes and rallies, but I will hold out. Not because I’m stubborn, but because it’s the interest of my country,” Sarkozy warned. True to his word, national railway strikes began on November 14. Overnight, one of the world’s most hyper-functioning public transportation systems literally shut down, paralyzing France at a daily rate of 300-400 million Euros in losses for the SNCF and the RATP (France’s state-run train companies).

Sarkozy was uncharacteristically quiet. He gave his last public address on November 13 and then disappeared for the duration of the crisis. In his absence, Prime Minister François Fillon proved that he could speak Sarko, too. “I already demonstrated in the past that I am not the kind to give up. I am ready to face crises and even unpopularity.”

Bernard Thibault, general secretary of the CGT—the union with the most railway worker members—expressed his willingness to negotiate even before the strikes began, as did Anne-Marie Idrac, President of the SNCF. But the government didn’t schedule meetings until November 21, the eighth consecutive day of strikes, when all three parties sat down to round table discussions. The strikes ended the next day.

Nothing was agreed upon at the meeting, although hefty salary bonuses—around 90 million euros a year—were proposed by the SNCF/RATP to compensate delayed retirements over the next fifteen years. More meetings were scheduled and canceled for mid-December, then rescheduled for January. The fate of the régimes spéciaux hangs in limbo.

But even without any real change, Sarkozy can declare his “first political test” a success, thanks to the unflinching government. He himself couldn’t have written a better sequel to the 1995 manifestations: “millions of French hoof it for miles to work during the debilitating 2007 railway strikes, but this would not be enough to deter the determination of the Sarkozian government in implementing profound social reform…”

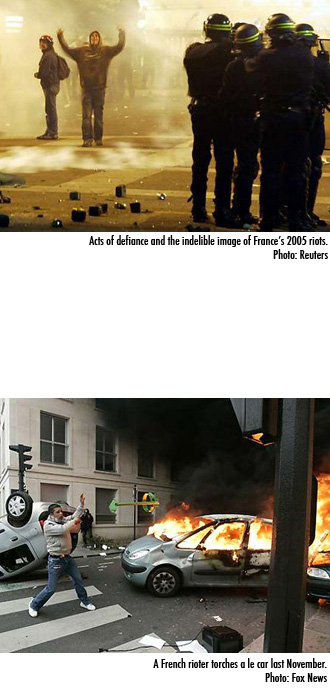

The lull in social unrest, however, was temporary. On the night of November 25th, the deadly collision of two youths with a police cruiser in the Paris suburb of Villiers-le-Bel started violent rioting. For three days and two nights, France relived the drama of October 2005, when the accidental electrocution deathsof two youths in Clichy-sous-Bois sparked 11 days of riots across the country.

The lull in social unrest, however, was temporary. On the night of November 25th, the deadly collision of two youths with a police cruiser in the Paris suburb of Villiers-le-Bel started violent rioting. For three days and two nights, France relived the drama of October 2005, when the accidental electrocution deathsof two youths in Clichy-sous-Bois sparked 11 days of riots across the country.

Two years ago, Sarkozy, then Interior Minister and Presidential hopeful, fanned the national riot and media flames with terse insults. He coined the name racailles, literally “scum,” for the burbs’ youth, and used the term so openly that so-called racailles physically denied him access to urban suburban areas. But this time, he was physically absent, abroad on his first official trip to China. There, he finalized contracts between China and French companies worth 20 billion Euros, including the sale of 160 new Airbus airplanes.

In his place, Michèle Alliot-Marie, his successor as Interior Minister, paid a surprise visit to Villiers le Bel amidst the riots. The visit, officially, was aimed at assuring a just investigation of the accident and went duly unnoticed. Miss Alliot-Marie has no public aspirations to become president.

The riots themselves differed greatly from those of 2005. For the first time, armed rioters open fired on police. Youths declared that they would kill two police officers for the two teenagers they lost. It finally took 2,000 riot police to “calm” Villiers-le-Bel, but the radicalization of the violence succeeded in highlighting Sarkozy’s failure to fulfill pre-election promises of “cleaning up” the suburbs.

Fadela Amara, France’s Secretary of State for Urban Policies, was also blatantly silent. She is in charge of attacking the problem and is at work on the much anticipated “Marshall Plan” for the suburbs, which will be unveiled on January 22. The plan should earmark millions of Euros for “ghetto” reconstruction. But will the money succeed in jump starting the economy in places like Villiers-le-Bel where, in certain neighborhoods, as much as 40 percent of the population is unemployed?

On Monday, December 10, Sarkozy celebrated Human Rights Day by welcoming Colonel Muammar al-Gaddafi, the dictator of oil-endowed Libya, to Paris. Colonel al-Gaddafi has ruled Libya since 1969; Libya was held responsible for the terrorist attacks on Pan Am Flight 103, which killed 180 Americans in 1988, and UTA Flight 772, which killed 54 French people in 1989.

Sarkozy was the first western head of state to officially host al-Gaddafi. He hoped that the visit would be “a success” and lead to a “certain number of economic agreements.” Instead, it lead to outspoken criticism. “France is not a doormat where a leader, terrorist or not, can come to wipe off his bloody feet from his own hideous crimes,” explained Rama Yade, France’s Secretary of State of Foreign Affairs and a member of the UMP, the right-wing political party that Sarkozy belongs to. Sarkozy was also the only European Union leader to congratulate Vladimir Putin on the success of his party, Russia United, in Russia’s highly-criticized legislative elections on December 2nd.

Optimistically, these two gestures mark the dynamism of France’s President. In an effort to usher in a more modern phase of French politics, he is reaching out to new, albeit controversial, territory. Yes, al-Gaddafi was a terrorist, but he has made significant progress in human rights in the past decade, including the dismantling of Libya’s nuclear arms program. Realistically, the moves could be purely economic. Sarkozy has often eluded to his private sector ambitions once his career in the public sector runs its course. As CEO of France, Inc., he is profit maximizing and building his resume.

For now, little has tangibly changed in France under Sarkozy. His term appears to be a glorified continuation of his electoral campaign, ripe with more opportunity for exposure across the world. He is a new breed of French President, hyper-mobile and super-present on the international scene, but he appears more interested in making splashes heard ‘round the world than sitting at home to deal with sticky domestic issues.

The New Year should prove more concretely insightful. Negotiations on the régimes spéciaux will pick back up. The government’s solution for the suburbs will be disclosed. The fruits of Sarko the diplomat may be harvested. And, although his fascinating private life is currently overshadowing the successes and failures of his public work, Miss Bruni might have a greater effect on French politics than Richelieu under Louis XIII. Since her arrival, Sarkozy’s persona has shifted from brooding to exuberant, positive proof of the virtues of copulation.