Robert Rauschenberg’s Combines at MOCA Los Angeles

18.09.06

Robert Rauschenberg’s Combines at MOCA Los Angeles

Robert Rauschenberg’s Combines at MOCA Los Angeles

September 2006

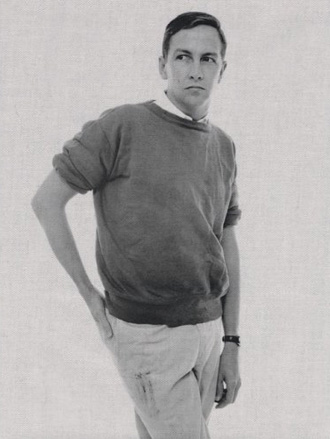

Oil, paper, fabric, wood, engraving, printed reproductions, and printed paper on canvas and wood with four Coca Cola bottles, bottle cap and unidentified debris, reads the materials list for 1958’s Curfew (Plate 79). Dark and formal as a Gothic window glimpsed at night by passersby, Coca Cola bottles gleaming like bars on a locked cell, panes cracked with yellowed etchings, the bull treading upon the wolf, hunk of coal glittering from within a recess, the prisoner’s watchful, dying eye. I like to imagine the artist as a young man, trolling his 1950s Greenwich Village neighborhood, crisp white shirt sleeves rolled up beneath a soft-wool sweater, pale and downy as a baby chick, filling the pockets of his paint-besmirched jeans with “unidentified debris.” The Museum of Contemporary Art’s Robert Rauschenberg: Combines exhibition is not only the first show consisting completely of Combines since Rauschenberg’s first museum show at the Jewish Cultural Museum in 1963, but a call for the return of the gentleman artist—one equally at home in the studio in a smart sweater and paint-splattered loafers or, alternately, (and just as good) rollerskating whilst wearing a parachute.

In the first of seven galleries dedicated to Rauschenberg’s, at-times, sprawling combines at MOCA’s impressively scaled exhibition, eleven pieces belonging to MOCA’s permanent collection—the rest on loan from various international museums—stands Minutiae (1954, Plate 15). Freestanding on legs, the patchwork curtain, red paneled, homemade armature is one of Rauschenberg’s first forays into three dimensions and is the bridge between his early, transitional Red Paintings made between 1953-54 and his later, highly sculptural combines, made from 1954 to 1964. Originally used as a set for a John Cage and Merce Cunningham (Rauschenberg’s old school chums from Black Mountain College in North Carolina) performance piece, Minutiae emphasizes the performance aspect of Rauschenberg’s work. Called by Jasper Johns as “the man who in this century invented the most since Picasso,” Rauschenberg personifies artist. Not solely a painter, sculptor, or performer, but an artist for whom life itself is the work, whose guiding principle is to “act in the gap.”

In the first of seven galleries dedicated to Rauschenberg’s, at-times, sprawling combines at MOCA’s impressively scaled exhibition, eleven pieces belonging to MOCA’s permanent collection—the rest on loan from various international museums—stands Minutiae (1954, Plate 15). Freestanding on legs, the patchwork curtain, red paneled, homemade armature is one of Rauschenberg’s first forays into three dimensions and is the bridge between his early, transitional Red Paintings made between 1953-54 and his later, highly sculptural combines, made from 1954 to 1964. Originally used as a set for a John Cage and Merce Cunningham (Rauschenberg’s old school chums from Black Mountain College in North Carolina) performance piece, Minutiae emphasizes the performance aspect of Rauschenberg’s work. Called by Jasper Johns as “the man who in this century invented the most since Picasso,” Rauschenberg personifies artist. Not solely a painter, sculptor, or performer, but an artist for whom life itself is the work, whose guiding principle is to “act in the gap.”

“My art is about paying attention – about the extremely dangerous possibility that you might be art,” Rauschenberg is quoted as saying.

Picasso validated this idea of artist as performer when he appeared drawing pictures with colored light in a darkened room, and painting behind glass in the 1951 Clouzot film le Mystere Picasso. 1954’s Elaine’s Party (Plate 5) includes a news clipping with the blaring headline “DE KOONING DRAWS LIGHT,” delineating the lifelong death spiral (off ice) a la Picasso, De Kooning, and Rauschenberg—ambivalence toward, yet reliance upon, one’s predecessors, whether through imitation and homage or obliteration and literal erasure.

Picasso validated this idea of artist as performer when he appeared drawing pictures with colored light in a darkened room, and painting behind glass in the 1951 Clouzot film le Mystere Picasso. 1954’s Elaine’s Party (Plate 5) includes a news clipping with the blaring headline “DE KOONING DRAWS LIGHT,” delineating the lifelong death spiral (off ice) a la Picasso, De Kooning, and Rauschenberg—ambivalence toward, yet reliance upon, one’s predecessors, whether through imitation and homage or obliteration and literal erasure.

Rauschenberg’s combines draw sparks with their juxtapositions of decaying photographs and newspaper clippings, found objects and pigment swaths. Although traditionally picturesque, as one moves about them, images and objects seem to multiply in dreamlike succession, liberated by the third dimension. Here execution and observation are equally theatrical; these pieces invite the viewer to circle around them, to scrutinize and inquire, to see the world as the gentleman artist on rollerskates. “There is no reason not to consider the world as one gigantic painting,” says Rauschenberg.

Rauschenberg’s combines draw sparks with their juxtapositions of decaying photographs and newspaper clippings, found objects and pigment swaths. Although traditionally picturesque, as one moves about them, images and objects seem to multiply in dreamlike succession, liberated by the third dimension. Here execution and observation are equally theatrical; these pieces invite the viewer to circle around them, to scrutinize and inquire, to see the world as the gentleman artist on rollerskates. “There is no reason not to consider the world as one gigantic painting,” says Rauschenberg.

The work of Matthew Ronay comes to mind, sculpturally at least, when considering the next loop in the multigenerational death spiral. His assemblages of constructed rather than found objects, like Rauschenberg’s combines, play out myriad, open-ended allegories and playful exploitations of chance, elucidating the pathos/ethos of mutually distant everyday objects thrown together in such a way that, in the end, makes some strange perfect sense. It’s also unified by an “all-overness” coating of paint, Abstract-Expressionist dribbles and smears transformed into the smooth, comic book Lite Brite-ness of mass produced toys, but with a post-Pop, formal quality of meticulously handmade sculpture.

The work of Matthew Ronay comes to mind, sculpturally at least, when considering the next loop in the multigenerational death spiral. His assemblages of constructed rather than found objects, like Rauschenberg’s combines, play out myriad, open-ended allegories and playful exploitations of chance, elucidating the pathos/ethos of mutually distant everyday objects thrown together in such a way that, in the end, makes some strange perfect sense. It’s also unified by an “all-overness” coating of paint, Abstract-Expressionist dribbles and smears transformed into the smooth, comic book Lite Brite-ness of mass produced toys, but with a post-Pop, formal quality of meticulously handmade sculpture.

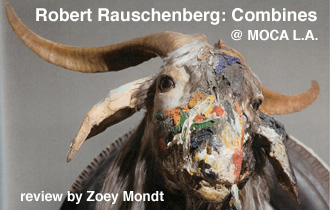

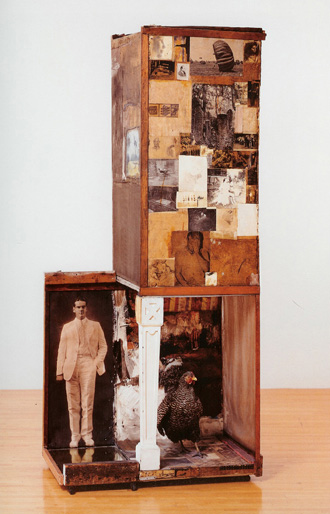

It has been suggested that no reproduction of Rauschenberg’s seminal work, Monogram (1959), can do it justice. I was disappointed (understatement) to find the dusty horned goat with its crimped silver fur girdled by an old tire, a profoundly sad, paint dabbled face and opaque eyes, seared tennis ball pooped onto a collage of newsclippings, boot heel, and police barricade encased in Lucite. Rather than the fathomless experience of stumbling into the back of some dank Wyoming watering hole to discover dilapidated taxidermy adorned by drunks, tire, paint et al, in which the unbelievable circumstance is somehow made believable, viewing Monogram here was instead like discovering Sleeping Beauty in her glass coffin in the forest. Precious, and dead. As Rauschenberg says: “Painting is always strongest when in spite of composition, color, etc., it appears as a fact, or an inevitability.” A few other pieces, Odalisk (1955/58, Plate 29) and Untitled (1954, Plate 28) were similarly embalmed behind Lucite, their casters permanently immobilized, stuffed birds peering out from the freezer section at Ralph’s.

It has been suggested that no reproduction of Rauschenberg’s seminal work, Monogram (1959), can do it justice. I was disappointed (understatement) to find the dusty horned goat with its crimped silver fur girdled by an old tire, a profoundly sad, paint dabbled face and opaque eyes, seared tennis ball pooped onto a collage of newsclippings, boot heel, and police barricade encased in Lucite. Rather than the fathomless experience of stumbling into the back of some dank Wyoming watering hole to discover dilapidated taxidermy adorned by drunks, tire, paint et al, in which the unbelievable circumstance is somehow made believable, viewing Monogram here was instead like discovering Sleeping Beauty in her glass coffin in the forest. Precious, and dead. As Rauschenberg says: “Painting is always strongest when in spite of composition, color, etc., it appears as a fact, or an inevitability.” A few other pieces, Odalisk (1955/58, Plate 29) and Untitled (1954, Plate 28) were similarly embalmed behind Lucite, their casters permanently immobilized, stuffed birds peering out from the freezer section at Ralph’s.

In the final gallery stands Gold Standard (1964, Plate 170), the last combine Rauschenberg made. Consisting of a gold, Japanese folding screen laden with objects ranging from an old boot, a clock, a cardboard box, electric lights, and a construction barricade, along with a small ceramic RCA/Victor dog tied to a bicycle seat, Gold Standard embodies Rauschenberg’s inclination towards ambiguity. Embittered by queries, Rauschenberg refused to answer a reporter’s questions, instead replied by merely adding objects to the screen. This aggressive inconclusiveness contradicts MOCA’s curatorial decision to include in the piece descriptions on the museum walls not only title, date, and materials used, but blurbs defining for viewers the artist’s intent and even directives on how each piece ought to be viewed. An established critic once told me, “Art is not about education.” What fun is there in being told what to think, especially about art? In a small corner of Minutiae there is a clipping of the funny pages’ The Little King in which his royal highness attends an exhibition of modern sculpture. Rauschenberg’s inclusion of this clipping illuminates his questioning of sculpture, exhibition, and context. I wonder how his Majesty would feel about MOCA’s installation and its insipid insinuations.

In the final gallery stands Gold Standard (1964, Plate 170), the last combine Rauschenberg made. Consisting of a gold, Japanese folding screen laden with objects ranging from an old boot, a clock, a cardboard box, electric lights, and a construction barricade, along with a small ceramic RCA/Victor dog tied to a bicycle seat, Gold Standard embodies Rauschenberg’s inclination towards ambiguity. Embittered by queries, Rauschenberg refused to answer a reporter’s questions, instead replied by merely adding objects to the screen. This aggressive inconclusiveness contradicts MOCA’s curatorial decision to include in the piece descriptions on the museum walls not only title, date, and materials used, but blurbs defining for viewers the artist’s intent and even directives on how each piece ought to be viewed. An established critic once told me, “Art is not about education.” What fun is there in being told what to think, especially about art? In a small corner of Minutiae there is a clipping of the funny pages’ The Little King in which his royal highness attends an exhibition of modern sculpture. Rauschenberg’s inclusion of this clipping illuminates his questioning of sculpture, exhibition, and context. I wonder how his Majesty would feel about MOCA’s installation and its insipid insinuations.

Rauschenberg quotes pulled from the Robert Rauschenberg: Combines exhibit catalogue (2006)

images in order:

1. Monogram (detail) (1955-1959, Plate 114)

2. Curfew (1958, Plate 79)

3. Minutiae (1954, Plate 15)

4. Robert Rauschenberg in sweater.

5. Odalisk (1955-1958, Plate 29)

6. Untitled (1954, Plate 28)

7. Gold Standard (detail) (1964, Plate 170)