Rituals of the Body: Marina Abramovic and Yara Arts Group

08.05.10

Ancient rituals play a large part in Marina Abramovic’s current exhibition at MoMA, Marina Abramovic: The Artist is Present, which runs through May 31, and in Yara Arts Group’s recent performance at La MaMa E.T.C., Scythian Stones.

Ancient rituals play a large part in Marina Abramovic’s current exhibition at MoMA, Marina Abramovic: The Artist is Present, which runs through May 31, and in Yara Arts Group’s recent performance at La MaMa E.T.C., Scythian Stones.

Entering Abramovic’s exhibit calls for a ritual all of its own. On a Friday afternoon I waited in line along with thousands of other museum-goers. On the particular day that I went to see Abramovic it was cold. None of my outer-layers seemed to protect me against the wind. I found myself trying to think on Abramovic’s terms. She would block out the cold, evidenced by the way she doesn’t seem to notice her surroundings as she sits in one position at MoMA, from open to close, at a table with an empty chair across from her in which museum-goers can sit as long as they want. She would forget. Whether it was due to the sun collecting between buildings, the bright glow of the Radio City Music Hall sign, or simply the promise that the line would soon start moving forward; my thought process proved successful.

In one of the rooms of Abramovic’s exhibit, accessible by passing between two nude models that stand close enough together to make the experience uncomfortable, she portrays three fertility rituals. In a video, men fuck the grass, some more ardently than others, to bring a good harvest. In a second video, a woman in an embroidered shirt and black scarf looks up to the sky and rubs her breasts, an act to precipitate rain during drought. In a third video, women in folk costumes run through a field lifting their skirts, sometimes letting their bodies fall to the ground (based on the legend that revealing one’s genitals to the rain will make it stop). Abramovic created these pieces after the end of her great relationship and partnership with Ulay, an artist with whom she had an intense collaboration and was also her lover. They marked their break-up with Lovers, a piece from 1988, when they walked from opposite ends of the Great Wall to meet in the middle. The parting caused her to question her own personal, cultural, and national identity, and to return to these ideas that were an inherent part of her culture.

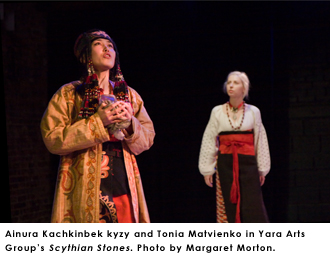

Because Abramovic’s work relies heavily on ritual, it coincides with Yara’s. Yara’s performance relied on rituals of the parting of mother and daughter to portray the importance of the passing of tradition. One mother-daughter pair was played by Kyrgyz artists Kenzhegul Satybaldieva and Ainura Kachkynbek kyzy. The other mother-daughter pair was played by a real mother and daughter, Ukrainian artists Nina and Tonia Matvienko.

As the mothers in the Yara performance prepare their daughters for departure, they adorn their bodies and hair, which intimately connects mother and daughter. In the Abramovic exhibition, the connection between the two models exists through the interweaving of their differently colored hair as they sit back to back. Both rituals create a unique artistic experience in which the body is essential. According to scholar Maria Maierchyk, in Ukrainian culture hair was once covered with marital oil, which would bring storms and rain to encourage fertility.

The Yara performance included ancient wedding songs. In Ukrainian culture the wedding is seen as a time of mourning, a wedding-funeral, because the mother was eternally separated from the daughter. “When I leave some things will linger with you/ My sweet tears will always grace your table,” the daughter reassures her mother in one of the wedding songs sung in Scythian Stones. Other rituals included the capture of the bride. The rituals focus on women.

The Yara performance included ancient wedding songs. In Ukrainian culture the wedding is seen as a time of mourning, a wedding-funeral, because the mother was eternally separated from the daughter. “When I leave some things will linger with you/ My sweet tears will always grace your table,” the daughter reassures her mother in one of the wedding songs sung in Scythian Stones. Other rituals included the capture of the bride. The rituals focus on women.

The performance’s stage was in the shape of DNA helix constructed by set and light designer Watoku Ueno. The helix, a recipe for life, conveys the passing of tradition through genes. It gives the actors the opportunity to be on both higher and lower levels, and creates a perfect situation to show the parallels between the Kyrgyz and Ukrainian worlds that are portrayed through dress, songs, rituals, and words.

The show began with Nina Matvienko, a legendary national artist, dressed in a traditional costume. She sings a song imploring a great harvest. “Oh the eagle plowed the field,” she sings and moves her body as if she were an eagle. According to Maierchyk, the bird often represents the soul. The mother may have been hinting at her soul flying away in the form of her daughter. The song also included a prayer for the harvest. The girls were that harvest. The eagle returned later in the piece, after the Kyrgyz daughter left home (soaring like an eagle).

As the girls let their hearts guide them on their own, they fell into the great below where they are ominously greeted by Susan Hwang and Maria Sonevytsky of the girl group Debutante Hour. This vision included a poem by Mary Karr in which hell is an armchair in the front of a TV, “Instead a circle of light opened on your stuffed armchair.” This brought the ritual aspect of the performance into the present day.

“I know I will die a difficult death – / like anyone who loves the precise music of her own body,” the Yara performers recite before leaving the stage, accentuating the fact that partings are sometimes arduous. Through her exhibition at MoMA, Abramovic also proves to love the music of her own body. She sits still conducting a silent interview with the museum-goer. Her stillness and intense gaze chisels away at the museum-goer’s confidence. The museum-goer swallows, lowers his or her head, and finally gets up and walks away.

There is beauty in the ritual of the parting.