Reviews: Wayne Koestenbaum’s Hotel Theory and Masha Tupitsyn’s Beauty Talk & Monsters

26.08.07

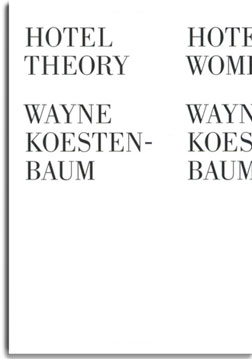

In Hotel Theory, Wayne Koestenbaum presents two apparently disparate parallel narratives, running them on each side of the page. The left side consists of eight note-filled dossiers, the collective mission of which is to “refurbish the meaning of hotel.” The right side, a “dime novel,” tells the story of Lana Turner, Liberace, and their respective families at Hotel Women, a luxury resort situated directly across the street (i.e. page). Each text regards the other through windows and frames, theoretical and fictional, interacting like voyeurs performing from adjacent buildings. Together they function as yet another, ever-changing story. Consider them the right and left sides of the author’s brain: the left capturing the melancholic solitude of a certain itinerant state of mind; the right, using Sirkian strategies of melodrama, subverts that sensibility by articulating a frivolous, fictitious underbelly for it. Each arrives at roughly the same place, an unwritten, bittersweet loneliness located somewhere at the center of the book’s blank middle column.

In Hotel Theory, Wayne Koestenbaum presents two apparently disparate parallel narratives, running them on each side of the page. The left side consists of eight note-filled dossiers, the collective mission of which is to “refurbish the meaning of hotel.” The right side, a “dime novel,” tells the story of Lana Turner, Liberace, and their respective families at Hotel Women, a luxury resort situated directly across the street (i.e. page). Each text regards the other through windows and frames, theoretical and fictional, interacting like voyeurs performing from adjacent buildings. Together they function as yet another, ever-changing story. Consider them the right and left sides of the author’s brain: the left capturing the melancholic solitude of a certain itinerant state of mind; the right, using Sirkian strategies of melodrama, subverts that sensibility by articulating a frivolous, fictitious underbelly for it. Each arrives at roughly the same place, an unwritten, bittersweet loneliness located somewhere at the center of the book’s blank middle column.

“A deluxe hotel (five hundred rooms) contains five-hundred destinies,” notes Koestenbaum’s left side. “Some rooms shift occupancy, night to night. Others contain permanent residents.” As in the dossiers of Joseph Cornell’s legendary basement archives, figures from literature, music, and film make appearances in Hotel Theory, reconfiguring its conceptual geography by checking in and out of its rooms. “Each room in a hotel is a now,” writes Koestenbaum, “but each now disregards the next, nor is there a coherent point of view that can legislate the serial progression of now to now, of next to next, or articulate it as a sequence rather than a simultaneity.” The same could be said of the two texts comprising Hotel Theory, which are absorbed by the reader like the twin screens of “Chelsea Girls”. As with Warhol’s twelve-reel opus, originally intended to be shown in whatever order the projectionist chose, Hotel Theory is a Kama Sutra of possibility, in which the variables of interpenetration are endless. Koestenbaum’s meditation on hotel state-of-being, like that film, contains a series of walk-ons: Tennessee Williams and his surrogate characters—themselves rooms to hide in—Chopin, Tallulah Bankhead, and Joseph Cornell, whose boxes are themselves like rooms.

It’s not surprising that Koestenbaum admits (or boasts) to being a very sexually-preoccupied person, describing his work habits in terms of impulse and stamina. “I get kind of obsessed and manic,” he says, “and work daily on the process and just keep going until I run out.” A gleefully intense polymorphous perversity is on full display at Hotel Women, where Liberace’s “pampered yet manly organ” spends as much time in as out of his swimming trunks. Liberace caresses Lana’s breast. Lana fondles Liberace’s nipples. “Hard wet sand offer[s] pleasant resistance.” Deliberately flat, Hotel Women remains perpetually hot and bothered, yet, excepting suntan lotion, never quite reaches the exchange of fluids.

Koestenbaum thrives on such combustible abstinence, the illicit tension between the excessive and the incomplete. Restricting himself or his characters in some almost punitive way, he creates an order or a system from which they, and he, may enjoy a broad spectrum of deviation. Often, his characters are rehabilitating, trying to get some impossible urge, frequently libidinal, under control, or at least kept to a minimum. In Moira Orfei in Aigues-Mortes, protagonist Theo Mangrove tries to curb his patronage of hustlers. In Hotel Theory, Liberace has been sent to Hotel Women by his parents for some unnamed impropriety, possibly involving binoculars. Discussing Model Homes, his book-length, ottava rima poem, Koestenbaum speaks of “allowed topics” and rules, those imposed by the dictates of the form, others by himself. In writing Hotel Women, he imposed restrictions on his “unruly syntax”; the words “a”, “an” or “the” could never occur, a strategy of omission he refers to as a personal salvation. “I’m totally into punishing narrative,” he explains.

Masha Tupitsyn, whose first book, Beauty Talk & Monsters, was recently nominated for the 2008 Young Lions Fiction Award, seems to regard her text similarly, engaging in a love/hate relationship with her source material (movies, particularly; other people in general). “I don’t think anyone really takes reading seriously,” she observes in “Reading is a Nightmare”, in a tone which exemplifies the book’s authorial impatience with the ways people choose not to commit, “and when they do, it’s because they’re readers themselves. But even then, they treat it purely as an act of pleasure, which it isn’t.” Beauty Talk, like Hotel Theory, is in part a meditation on the symbiotic pleasures and impositions of intellectual exile—at once an indictment and a celebration—a poetic expression of voluntary solitude which questions what it means to hole up inside yourself, to resist the roles you’ve been assigned and the thoughts you’re conditioned to accept as your own, and to willfully separate from the disappointment of other people without losing your engagement in and appraisal of the world around you.

Masha Tupitsyn, whose first book, Beauty Talk & Monsters, was recently nominated for the 2008 Young Lions Fiction Award, seems to regard her text similarly, engaging in a love/hate relationship with her source material (movies, particularly; other people in general). “I don’t think anyone really takes reading seriously,” she observes in “Reading is a Nightmare”, in a tone which exemplifies the book’s authorial impatience with the ways people choose not to commit, “and when they do, it’s because they’re readers themselves. But even then, they treat it purely as an act of pleasure, which it isn’t.” Beauty Talk, like Hotel Theory, is in part a meditation on the symbiotic pleasures and impositions of intellectual exile—at once an indictment and a celebration—a poetic expression of voluntary solitude which questions what it means to hole up inside yourself, to resist the roles you’ve been assigned and the thoughts you’re conditioned to accept as your own, and to willfully separate from the disappointment of other people without losing your engagement in and appraisal of the world around you.

Disguised as a series of short stories, Beauty Talk is in fact a collection of tightly wrought, multi-layered observations, many of them about women who seek the kind of “apartness-as-refuge” to which Koestenbaum refers. Sometimes, refuge is sought from other people; other times, from other people’s limiting opinions and extravagant selfishness. Tupitsyn articulates how such “apartness” sits with other people. Her writing, like the dark-haired, “angry” girl of Beauty Talk’s “Metablondes” (along with “Kleptomania”, one of the best pieces in the book) displays an insatiable, restless intellect with a mixture of resentment for having to justify it and pride in her frequent refusal to do so: “Why are you always so fucking obvious and traditional when it comes to having fun?” allegedly angry “M” asks her popular, allegedly uncomplicated blonde friend, who accuses her of being too serious, too perversely complex and solitary. Popular blonde friend plays the game by established rules, wiggling the right things, silencing the wrong, in a way that most of the women in Beauty Talk find despicable, if not impossible. In Beauty Talk’s scenarios, there’s no such thing as solidarity, and the argument could be made that solitude is the only choice from the beginning:

L stepped on M’s Brain and the way M thought about things like a foot-stool. M always pulled the stool out from under L. It was their routine, a circus-act, until they were fifteen and M split off like the Siamese twins in Sisters […]

This kind of writing wants to switch rooms frequently. Constantly changing views, it reinvents itself in ways that are as organic as Koestenbaum’s rules are regimented. Tupitsyn takes an architecture like the one proposed in Hotel Theory, a system, and reconfigures it, interchanging not just its inhabitants, not just its rooms, but the specific, distinguishing components which make each recognizable as such, recombining these facets to make an entirely new whole. She’s not exactly opposed to genre, just rather impatient with its façade of facile reductions. Like Koestenbaum, she has something of a voracious curiosity regarding possibilities, but where he tends to draw a line, if a thin one, dividing neatly down the middle two impossible oppositions, Tupitsyn banishes any such segmentation altogether, embracing both the vagaries and the advantages of hybridization as a more realistic, if not more readily embraced, representation of self within society.

What seems to be a story about the protagonist of Hitchcock’s Marnie, Diane Keaton, and Judy Garland meeting for cocktails shifts suddenly, in “Kleptomania,” into entirely unfamiliar territory, moving from a critical evisceration of Jack Nicholson’s endless imitation of himself to the mostly female cast of The Witches of Eastwick and the contortions they perform in order to play supporting roles to his caricature. “I get the horrible feeling that movies are so fucking sneaky,” she writes. Less stealthily, the piece zigzags kinetically from issues of memory and memoir to doubles and double standards. Somewhere within these permutations, the narrator, whoever that is, rents an endless series of movies from Netflix, changing them like costumes and sets, marveling at how movies by turns constrict and liberate her, romanticizing her solitude then turning it into outright loneliness. The one thin line Tupitsyn maintains is that between on-screen and off-screen. Pop culture is subject, theme, character, and plot in her work, which takes American media as a narrative foundation, a set of Lincoln Logs with which to construct and tear down rooms that might give shelter to her thoughts.

What seems to be a story about the protagonist of Hitchcock’s Marnie, Diane Keaton, and Judy Garland meeting for cocktails shifts suddenly, in “Kleptomania,” into entirely unfamiliar territory, moving from a critical evisceration of Jack Nicholson’s endless imitation of himself to the mostly female cast of The Witches of Eastwick and the contortions they perform in order to play supporting roles to his caricature. “I get the horrible feeling that movies are so fucking sneaky,” she writes. Less stealthily, the piece zigzags kinetically from issues of memory and memoir to doubles and double standards. Somewhere within these permutations, the narrator, whoever that is, rents an endless series of movies from Netflix, changing them like costumes and sets, marveling at how movies by turns constrict and liberate her, romanticizing her solitude then turning it into outright loneliness. The one thin line Tupitsyn maintains is that between on-screen and off-screen. Pop culture is subject, theme, character, and plot in her work, which takes American media as a narrative foundation, a set of Lincoln Logs with which to construct and tear down rooms that might give shelter to her thoughts.

While they often include protagonists and themes, plots and plot devices, the pieces in Beauty Talk & Monsters sometimes read like cut-ups, creating juxtapositions within juxtapositions. This is narrative as Woman Descending the Staircase, the subject’s flickering visage challenging what Tupitsyn has referred to as a collective “notion of art as this autonomous wall that blocks out the messiness of the world.” Eschewing the pervasive tidiness which movies pass off as reality, a system which oppresses and alienates anyone in touch with the complexity of her feelings, Beauty Talk pushes fiction into black holes of potential created by the merging of mind and media. For Tupitsyn, spaces and walls like those in Hotel Theory are inevitably ubiquitous and fixed, solitude is precious but ultimately an imprisonment, and the free-form state of being Koestenbaum locates specifically in a hotel’s compartments is simply a more refined and diffuse confinement, its exits and ports of entry more elusive to locate.

Context is everything. Tupitsyn’s characters merge with other characters; are real, then unreal. Narrator openly merges with author, movie with viewer, resulting in something in-between. In “Web Life”, the narrator surfs the web for a sense of her former boyfriend’s present state of mind, seeking closure or some forbidden, fugitive intimacy from her estrangement. “I wasn’t allowed to be inside,” she says about her web search of the-private-as public life of someone who has long since shut her out, “but I am anyway because there is more than one way to get there.” Like Koestenbaum, she concludes, “There is more than just one inside.”

Hotel Theory is available from Soft Skull Press

Beauty Talk & Monsters is published by Semiotexte