Review: Who Gets To Call It Art

06.02.06

WHO GETS TO CALL IT ART

WHO GETS TO CALL IT ART

At Film Forum, 209 W. Houston Street, NY

Wednesday Feb. 1 through Feb. 14th

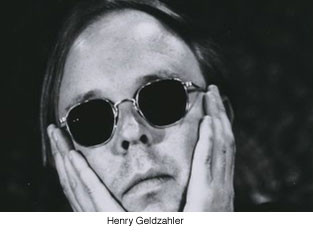

Henry Geldzahler once said: “The history of modern art is also the history of the progressive loss of art’s audience. Art has increasingly become the concern of the artist and the bafflement of the public.”

If the film, Who Gets to Call It Art, is about the debate over what makes something “art,” then Geldzahler––a curator and critic who played a key role in articulating the objectives of art made during his lifetime––is important to center out. The movie vacillates on this point, situating itself somewhere between a biography of Geldzahler (focussing on his life between 1960 and 1970) and an overview of the New York art world in the 1960’s. For better, though probably for worse, the film is not always entirely clear what its objectives are.

Director Peter Rosen blames such ambiguity on the film making process itself––the organic nature of shooting and editing: “You can’t really say what the film is about. It took its own form after we started putting the material together.” But Rosen said he would hate to have the film received as a biography of Geldzahler. Considering the curator was not a well known figure to the public, he felt there would be little draw to the general audience.

This is not to say that the logistics of selling the film wholly defined its shape. As Rosen indicates, it was the editing process. For example, the first sequence in the movie was put together with footage they had put aside because they weren’t sure what to do with it––an interesting creative choice, because the sequence was mostly indecipherable statements made by artists. Of the more remarkable clips is that of Barnett Newman saying: “Aesthetics are to the artist as Ornithology is to the birds.” Rosen likes this quote and thinks that the word aesthetics and his film are both really too vague to define what makes art good or bad. Rosen says his film “just covers this huge history from the 40’s until now with these basic unanswered questions.”

Ironically, Newman’s quote stands in stark contrast to his philosophical writing, which speaks at great length about aesthetics. It is unfortunate that like so many of the cast in this film, Newman is no longer alive.

When I asked Peter Rosen why he chose to begin this way, he explained that in setting up the movie with a number of baffling quotes by artists, he could underscore the importance of a man like Geldzahler, who had the ability to bring clarity of written and verbal expression to the visual world.

While there is some logic to this, it assumes that everyone believes the stereotype that artists do not express themselves well, and therefore a sequence of artists pontificating will simply reinforce these ideas. Since many of the statements made by artists in the opening sequence are exactly the sort of thing that leaves the general public feeling alienated and confused by the art world, these clips do more to reinforce Geldzahler’s observation that art has become the concern of the artist and the bafflement of the public than it does to show why he was needed. Notably, this quote at no point appears in the movie.

Despite these flaws, the film is excellent at contextualizing art made in the sixties, and much like today, art of the sixties built upon, and reacted to art that came before it. Without an awareness of this background, it is impossible to understand what Pop and other movements are all about. The film reveals by way of interviews with art world celebrities such as dealer Ivan Karp and critic Calvin Tomkins how natural the reaction to abstract expressionism was for artists during that period. Tomkins went so far as to call Abstract Expressionism “humorless and boring,” so it is no surprise that people grew tired of this method of expression. Rosen aptly sums up their observations: “Here were all these guys living within 20 blocks of each other, all within the same 5 or 6 or 7 years…all having this reaction.”

Perhaps a more powerful example (and yet another piece of history that did not make it into the movie) is the now classic story of the pop legend, Andy Warhol approaching dealer Leo Castelli in the early sixties. Warhol presented a series of drawings which were rejected because Castelli felt the work was derivative, and too similar to the work of Lichtenstein, an artist he already represented. Although Castelli would soon be the first to sell Warhol’s Campbell soup can prints, clearly, the pop art movement had begun well before Warhol garnered gallery representation.

If, as Ivan Karp suggests in the movie, Abstract Expressionism is about internalization, then Pop art’s reaction to this was to address the external. It is hard to say what specifically sparked the national debate about art, but certainly this shift played a part in it. As an art connoisseur and curator at the Met, Geldzahler was a key player in all of this, and as such, the movie uses him as the skeleton to hang the details of the decade. Rosen mentioned the idea of Geldzahler playing a Zellig type of character in this movie, someone who is featured working behind the scenes at all times, even though the movie isn’t really about him. Had there been enough footage of artists and curators making these connections in the film, this concept might have been brought to fruition a little more successfully.

Nevertheless, through countless artist, dealer, and critic interviews, the movie does succeed in showing Geldzahler to be a man of great passion and intellect whose keen eye and flamboyant personality made him a natural leader. Geldzahler’s greatest achievement, the conception and curation of the first contemporary art show at the Met, New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940-1970, was a result of his powerful personality, and as such a sizable portion of the film is devoted to discussing this point in Geldzahler’s career. It was also, as Geldzahler says, the last moment you could look at the art world coherently, and as such provides the perfect punctuation point to that time in art history.

Best illustrating the importance of the show and Geldzahler’s achievement, is a statement by painter Frank Stella who recalls that that it wasn’t until he saw his work hung in the museum that he realized just how great the exhibition space really was. On the surface this statement appears obvious, but what it reveals is the degree to which tradition had been entrenched within the institution, and the art world. Even the most innovative artists at the time, could not envision the Museum being used in this way.

Such statements demonstrate the freshness of ideas that are now commonplace to people during that time. Not surprisingly, Geldzahler’s show created a lot of controversy. There were many artists who were naturally upset about being left out of the show, and many critics over the choice of venue.

The film covers this superficially, though it would be a lot richer for greater inclusion of some of these artists. The ideal time to have shot this movie would have been about 10 year ago, since artists like Robert Rauchenberg, would not yet have suffered a stroke, Larry Rivers would still be alive, and Marisol Eschobar, might have been lucid enough to contribute to the film.

Rosen laments that he was unable to include any interviews with women who were part of that scene and acknowledges that it would have enriched the film greatly, but the artists approached all eventually declined. He really wanted Helen Frankenthaler to be in the film. “She can tell you how many times I called her. …. She was key to this. The fact that she was the only women in Geldzahler’s show was a great story for us to tell. So it’s really a shame, and I think my biggest regret in whom we could get in the film and who we couldn’t film is in not being able to work with Frankenthaler, because she was a really important part of Geldzahler’s sensiblities.” The lack of women was not for trying. Rosen said that Marisole was not in any condition to give an interview, and Louise Bourgeois, still very bitter about being left out of that show, wrote an email to the executive producer saying that she didn’t want to have anything to do with Henry Geldzahler.

Rosen says the film would have benefited greatly had they been able to find people who were left out who would talk about that show and what it may have done to their careers. “Being left out of the retrospective like that of the whole 30 years of American art is not the best thing for your career if you’re out there at that time… So we had a whole host of people we would have liked to have put in the film but you can’t get everybody.”

And it’s a shame, because despite its wealth of interviews, the most important are missing. Who Gets To Call It Art has the feel of a movie whose thesis was determined in the editing stage of the film making process as opposed to pre-production. The problems that can be encountered in this method of working are clear, because the interviews lack substance and direction. Rosen, of course, spins this more positively saying, “Because the whole film is like a Rauchenberg collage, it goes by really quick and you get this overview and feel for the period but not a huge in-depth look at any one particular artist or movement or minimalism. It’s not really that kind of film.” This comparison works for me too, because in addition to all this, much like a Rauchenberg collage, you never really know what you’re going to get. One moment you are taken in, and another you wonder why you are bothering at all.