Regarding Lil Ugly Mane and Abject Music

14.06.16

Questions of authenticity in music are a frequent and occasionally necessary plague. Crust punks in suburbs, the Rolling Stones’ appropriative empire, murder music made by moneyed club kids. Only with rap, however, is a certain credibility near mandatory. I’ve long held the belief that American rap in particular holds strong parallels with European black metal. The rhetoric is similar, steeped in death, forms of gluttony, sneering rejection of social cues and ways of being. Black metal, and death metal, for that matter, have—contrary to rap—carved themselves niche markets wherein said rhetoric can flourish untouched by howling media outlets and such. With rap, however, judgment and consideration are constant, and thus the parallels seem buried, lost amid more readily recognizable stereotypes than Fenriz’ paled skin. A sort of case: 90s suicidal heads Lo Down Da Sinista, whose Comin 4 Your Soul is every bit as nihilistic and blackened as Deathcrush, the lyrics depressive and working class, the presence masked and threatening.

Enter Lil Ugly Mane, a sort of one-man Crass of contemporary American rap. The work is self-reflexive, death-soaked, lost amid the shit of modern times. The figure himself, it’s uncertain. Bits and pieces exist around the internet. A performance following Brooke Candy in California alongside Antwon—another anomalous punk-inflected modern emcee. The mood, however, seems to be on the order of Richard D. James: it isn’t about the authenticity of the human animal responsible for the genesis of various releases under the Lil Ugly Mane header, but rather about the fabrication of a projected persona and the authenticity of its purpose.

Videos exist of said human animal performing noise music in an auditorium screaming “THIS IS WHAT YOU PAID FOR” at the audience repeatedly. On first discovering his music—by way of the phenomenal fan-made video of a man walking through various vistas holding a handgun for Lil Ugly Man’s “Throw Dem Guns”—I sifted through every bit of information I could find on him, discovering his association to a supposed punkhouse/pseudo-cult called the Church of Crystal Light, hearing rumors that he was perhaps attending law school; and it was after all of this that the above realization came. When I see Attila Csihar of Mayhem/Sunn O))) on stage, covered in fake blood, face painted so he looks like an ancient Viking corpse, lost in miserable growl about the antichrist, I’m not entirely preoccupied with the fact that Attila Csihar’s a father, and worked a pretty average day job prior to his present occupation. It’s interesting, yes, it’s pretty fascinating; but its existence as an aspect of his career does little or nothing to the texts with which he’s associated, nor the performances. When Lil Ugly Mane says “bitch I’m lugubrious/my trap game is stupidest/you actin’ like I’m new at this/I been sick since the uterus/I equate your uselessness/to bitches that are bootyless/your YouTube page is viewerless/it’s humorous” it would seem better seen as a projection, an abstraction of some reality, than someone’s diary. What’s happened, it seems, is the guts of someone’s misery and feeling has been transplanted into music, perhaps performance art though that seems slightly reductive. The strength of these projects isn’t the recreation of a great sound and era in rap; plenty of groups do a decent job of Lil Ugly Mane’s sound and yet never garner the same obsessive exploration. The strength would seem to be the murk between, the moments of Robert de Niro that creep through Travis Bickle’s disgust.

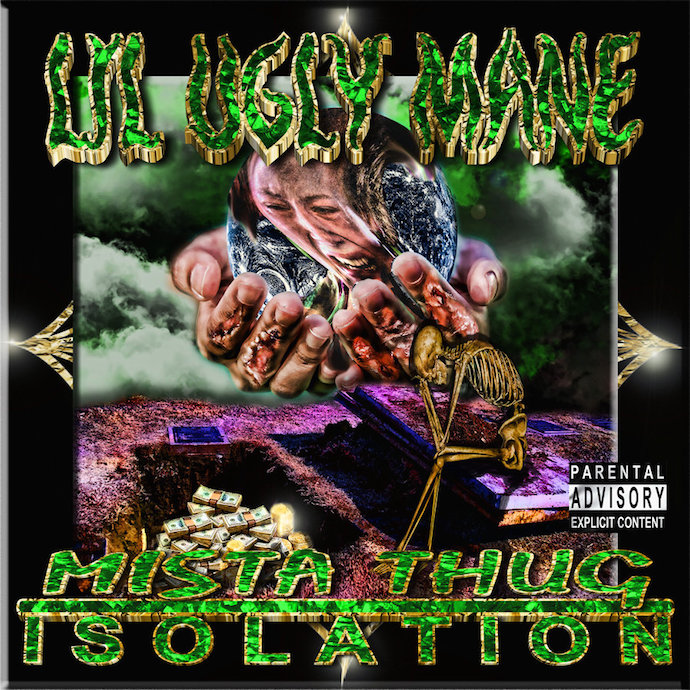

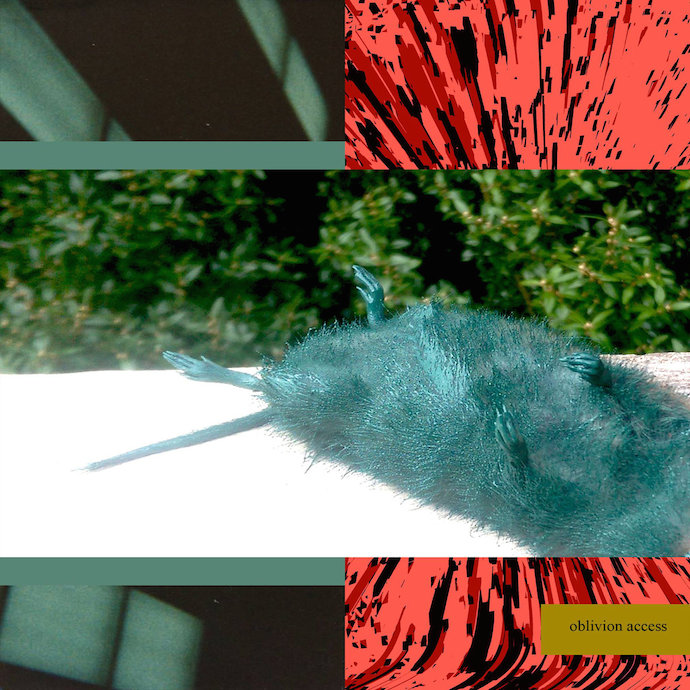

His most recent project, Oblivion Access, is apparently his final ode to the medium, and thus the work bears considering. Also released recently was his solo black metal project—he’s sampled this throughout his THREE SIDED TAPE releases—Sleep Until it Hurts You, under the moniker Vudmurk. The later releases of Lil Ugly Mane occupy a pretty much untouched area in hip hop, made of skepticism, self-reflexivity, and an abject sensibility equaled in large part only by someone like MC Ride. His later work has also grown more feature-focused, which seems to tie in with an ongoing theme of putting rappers on and maintaining support within a particular culture without worrying over money, popularity, or sales.

Although released physically by ORMOLYCKA, the bulk of L.U.M.’s work is most readily available via Bandcamp, a locus for punk and metal outfits of late interested in sharing work, not being fucked over too badly, and releasing quality digital products easy to access for fans. Interestingly—and this ties in with the overall feel of his work and aesthetic—one release, for his ten minute+ track Uneven Compromise—lengthwise itself already more emblematic of a metal aesthetic than a rap one—features the first page of an edition of Georges Bataille’s The Impossible. Bataille’s ideas make perfect sense when applied to the impaled sheep heads of black metal, an extremism in art handed down from the Divine Marquis to artists and writers disinterested in perpetuating the same political ideas, the same social ideas, the same critical ideas that’d left the world so vapid in Bataille’s day. Coming no closer still, the lens of Bataille in interpreting someone like Lil Ugly Mane seems helpful. We hear linguistic ability, literary ability, an intellect that’s sharp and as informed by contemporary newsfeeds as it is Raekwon or Big L, but there’s also that something else that leaks through, a threat perhaps hinting at the precariousness of identity, or if that’s too lofty then at least the sense that something beyond expectation is being vied for; something otherworldly and yet absolutely of this world, something popular yet impossibly unpalatable, something that’s frankly a bit of a nuisance to make sense of and something that wipes out all dogmatic thought. The virus of rap’s language in Burroughs’ sense. A mode of writing that eats contemporary America and removes its guts prior to whole digestion to reveal goldsoaked stage jewelry.

While all these matters persist through Oblivion Access and even his final Third Side of Tape release, there is again a new depth of abjection and disgust leaking through the sound. Notes on L.U.M.’s Bandcamp indicate that these works were held in various states over the past few years and slopped together as a final gesture toward the project—a “patriotic dry heave” as mentioned in the title to his On Doing an Evil Deed Blues. What’s interesting is that the most conventionally exciting or affirming tracks of his exist in projects more toward the middle of a brief career. These later works are pulled apart and willfully broken and far more noisome. It’s pleasant, to be sure, and as welcoming as the entirety of his catalog, but its as if the two ends of this project were set on fire leading to a fully realized implosion toward the center. Hip hop itself is a recursive thing, “so how’s it been forty years/and all we fucking rap about is weapons?” goes the lament in ODaEDB, and it’s not far off. What’s glossed over there though is the surrounding culture, the militia culture that still sops its subcultures up with so much bleach. Forty years is nothing in the trajectory of the human fuckup, and this hip hop is right on course as far as its evolution. We need work, though, that begs questions about the nature of the field itself. We need Throbbing Gristles for every Joy Division. We need Hank IIIs for every George Jones. We need Wolves in the Throne Rooms and Sunn O)))s for every Slayer or Judas Priest. Anomalous acts in the arts help to better solidify and explicate the merits of a given genre. Apparently fucked up takes on established masterpieces by Jean-Michel Basquiat only lead to fuller appreciation of either, or both, or a range of possibilities between. It would seem to fit this vein, the work of someone like Lil Ugly Mane. A disruption, a thorn in the side of a potentially stagnant culture.

The presentation of Oblivion Access itself is an ongoing thing, an endless point of consideration. The tracklisting warps language more engagingly than most contemporary poets, and a sort of manifesto accompanies the work:

“OBLIVION ACCESS IS THE LAST OF THE FILTHY WATER FUNNELING OUT OF THE BATHTUB I’VE BEEN SOAKING IN FOR 5 YEARS.

IT’S ALL THE SHIT AND CUM AND BLOOD AND PISS AND SWEAT AND FLAKES OF DEAD SKIN AND HAIR COLLECTING BY THE DRAIN. TOO THICK AND CLOTTED TO FIT THROUGH THE TRAP.

YOU HAVE TO DIG YOUR HANDS IN IT AND FUCKING DEAL WITH IT.

YOU HAVE TO PICK IT UP AND SMELL IT WHEN IT’S TIME TO CLEAN UP.

YOU HAVE TO LOOK IN THE MIRROR AT YOUR STUPID FACE AND PRUNED BODY SURROUNDED BY THE GHOSTS OF YOUR DEAD FRIENDS WHEN YOU WASH THE SHIT FROM YOUR HANDS

YOU HAVE TO STARE AT YOURSELF AND LOOK FORWARD TO SOMETHING INTERESTING.

OBLIVION ACCESS IS NOT A CLUB RECORD. THERE ARENT ANY HIT SONGS.

IT’S JUST ME AND A FRIEND SORTING THROUGH A BATHTUB OF MY SHIT AND GRIEVANCES IN A BASEMENT FOR A MONTH SO THE WATER COULD FINALLY DRAIN OUT AND I COULD GO HOME.

C YA L8R ;b

ALSO:

WATCHING DUDES CLAMOR AND COMPETE TO BE THE “FIRST” TO LEAK A RECORD IS LIKE WATCHING SOME DARK PEDO-CUCKOLD FANTASY GAMESHOW WHERE THE WINNER GETS CYBERWANKED AND TOLD THEY ARE COOL BY TEENAGE BOYS FOR ANOTHER MAN’S ACCOMPLISHMENTS.

I JUST POOPED.

ALSO:

EXPECT A FOLLOW UP OF REMIXED MATERIALS, RAW FILES, AND VARIOUS “BONUS” BULLSHIT”

After a range of mechanical, industrial sounds not unlike those that open Mista Thug Isolation, a theme presents itself. “Facts are human arrogance/We barely know a fraction”/”I don’t know, anything/I don’t know, anything” is repeated on “Columns,” a track roughly the rap equivalent of the Nietzsche Turin Horse episode, picking apart not only the tendency of rappers to assert understanding, but people in general. Information’s actually pretty constantly at stake in L.U.M.’s music, arguably the logical starting point for an artist engaging with their audience primarily by way of the internet. Just like Tonetta’s videos bring forth all kinds of questions about the nature of online performance, sexuality, and YouTube, the tracks throughout Oblivion Access seem heavily linked with the idea of rapper-as-writer, writer-as-interpreter-of-information. As with other releases, the production is an aggressive piling of 70s filmscore sounds, dejected instruments, whispery samples and amplified voices. The aforementioned industrial sounds affect everything, calling Throbbing Gristle to mind as much as DJ Paul.

It’s a love letter to the genre, and a particular strain of the genre. Hip hop made in a particular context wherein the only thing sufficient to one’s desired ends is a mixture of electrified rhythm and angry, miserable, violent writing.