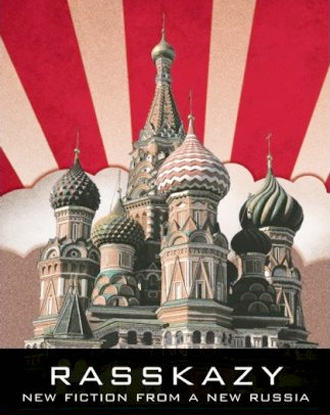

Rasskazy: New Fiction From a New Russia

23.08.09

Rasskazy: New Fiction from a New Russia

Rasskazy: New Fiction from a New Russia

edited by Mikhail Iossel and Jeff Parker

400 pages

Tin House Books

(September 1, 2009)

Rasskazy: New Fiction from a New Russia, which includes the work of about two-dozen young Russian writers and nearly as many translators, can be read as something of a survey of contemporary Russian literature. While many of the pieces here were previously published in Russian journals and magazines, this is the first time these writers have been published in America.

The idea of a new Russia enticed me. In both contemporary media and the popular imagination, the attraction to a stereotypical, dreary and neglected Russian cityscape, in which people furtively connect between shots of vodka and bouts of unhappiness, seems inescapable. Upon reading Rasskazy it becomes apparent that fiction from the new Russia too often relies on retreading these images of the past or, as in Arkady Babenko’s story “Diesel Stop,” which takes place in the dire landscape of Chechnyan conflict, history merely repeats itself. Oleg Zobern’s story “Bregovich’s Sixth Journey” highlights the preeminence of the past and the shadow of Russia’s cultural history: “The dead: they’re like family to me already. Take Tarkovsky, take Pasternak. There’s no place I’d rather drink a Crimean red with a girl than at Pasternak’s grave.”

The melancholy and apathy that flourish among people who lack control of their own fates fill many of these stories. Should we be concerned that Mikhail Iossel and Jeff Parker characterize the stories as “New Russian Realism” in their foreward? Aleksander Bezzubtsev-Kondakov’s “Russian Halloween” contains the bitterness of divorce, alcoholism, and loneliness. The past is contained in the landmark of the story itself, the Soviet-era block-style apartment building where Igor lives, which shapes his outlook on the world because it smells of “unhappiness and suffering.” In that apartment building he helps an alcoholic to his abode and he has sex with a young girl who frightens him with her foreign Halloween festivities. Even the image that represents a hopeful note connected with Igor’s friend’s decision to be born again by leaving his present life is concealed in ugliness: “A green Zhiguli six, which sped indifferently along the street toward the two of them, squealed its brakes and flew into a puddle covered in thin, caramel crustlike ice, almost splashing Anton with a murky wave.”

The stories that are more experimental in nature stand out and use their style to transcend the limitations of the past. “They Talk” by Linor Goralik is one of those stories. It is built on snippets of conversation that reveal psychological breakdown, discomfort, and distrust of friends and lovers. The most drastic example of conversation shows that while most of the characters in Rasskazy seem to be able to live with the unpleasantness in their lives, some are pushed to clinical breakdown. “…[W]hen he loved me, I wasn’t jealous, and when he didn’t love me—I was. I’d start calling, aggravating both myself and him, until one time an ambulance came for me.” “The Seventh Toast to Snails” is a similarly fragmented nautical love story with sentences that merit reading for the sake of their beauty such as, “Your skin burns even under your shirt, because the rays of the sun in that part of the world are so greedy that they penetrate even the weave of fabric,” and “What particularly attracted her to him was a singular facial expression that made her want to grab him by the chin.”

Although the collection might primarily be considered as a showcase of new Russian literary talent, it also serves as a stage for translators. In some of the pieces here the translation creates a reading experience as seamless as the original, while in others certain phrases stuck out so much that I began to wonder how the text might read in the original. Who were those city “fufus?” Why is a “mammy” present? And how did a shed acquire its “second half”? In translation there exists a fine line between inventing new linguistic concepts in the target language and simply falling short of an adept translation.

One recurring problem in Russian translation is sentences which, in the context of English appear to be egregious run-on’s. But Victoria Mesopir uses this technique to create a linguistic beauty that transcends the starkness of the story in her translation of Maria Boteva’s “It All Depends on Who You Believe.” “In front of us sits a person who is also in love but is scared to death of admitting it and taking some kind of steps we sat all night and listened, we had one bottle of champagne which of course we drank very quickly and what is there to talk about of course immediately there were five of us that’s probably about all and what is a bottle of champagne for five people it’s not even serious.”

I was attracted to the neglected landscape presented in Rasskazy––peeling leather-upholstered doors, a dog named after a famous prisoner, and a village called Paradise that is the opposite of paradise. While it is exciting to be exposed to this world that only exists on the periphery of my personal experience, I wonder if there are stories within the landscape of contemporary Russian literature that deviate in their tone as much as some of the stories in Rasskazy pleasurably deviate stylistically.

*BTW: Here’s the publisher of Rasskazy, Tin House.