QUICKSAND

12.07.17

My husband left me for a pile of bricks. I loved him for two years but we’d been married for ten.

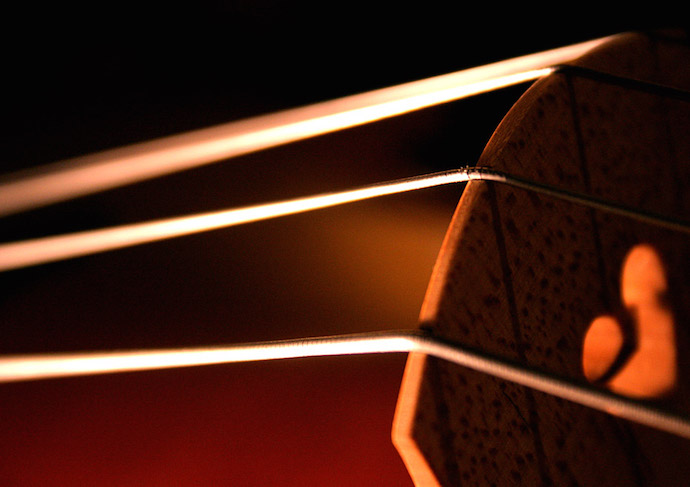

When we first met, he was a beautiful man. He had strong cheekbones and played the cello. I always said to my mother that I’d marry a cellist and when I did, I met her for coffee and stuck my tongue out at her in an act of defiance.

The hair of a mop, the eyes of a methadone addict. His fingernails were feminine and often painted and his abdominal area reminded me of an ironing board. His mouth was like the opening of a conch shell.

He owned many pleasant mahogany items, which he sometimes let me run my fingers across. He also liked to buy objects made of marble and would, on Sundays, go around the house and touch every marble object before going to bed. I can see him now walking around the house, touching the top of a fireplace, a cherub’s penis, stroking a miniature column.

But living with a cellist is not the same as dreaming about cellists and perhaps I should have realised this sooner, but men never live up to their profession. Perhaps the cello itself seduced me and, yes, maybe I should have married the instrument not the man.

My husband was cruel in the first year of our marriage. He impregnated me against my will. I didn’t want the baby to grow inside of me but it did and it grew there for nine months and it had the gall to get bigger too.

During those nine months, my husband played cello all day and all night without socks or shoes. He wore corduroy trousers and a corduroy shirt and I wanted to tell him that this was not okay, but I said nothing. I focused on my body.

The baby was about to be born, so we had to erase an important room in our house to accommodate it. So we decided to get rid of the library, the walls lined with books and memories, and in the baby would go.

I grew to love the idea of the baby the same way one’s tongue grows to love the taste of a vegetable you once hated as a child.

*

My husband noticed that after the birth, I started to become ugly. He pointed out that my vagina had lost its shape. Your hair, too, he said, is falling out, he’d say.

Your toes are still bloated.

Your breasts are constantly sad.

You have old woman veins on a young woman’s legs.

He compared me to a ship containing treasure during a tempest. There is a beauty there, he said, but it’s lost for all man to appreciate.

You’re a shipwreck.

And so after two years, love turned to nothing. I actually thought love was a thing, a physical object. I started looking for it in our house. I looked under the sofa, under the bed. I upturned the ottoman and looked there too. I looked in jam jars, butter dishes, raisin bowls, mugs, glasses, chiffoniers, beds, cupboards, steam trunks, washing machines, boxes, bins, ovens and attics.

*

When I was a young girl I tried my hardest to look like a woman. I put on make-up and wore high heels and bras. I moved in provocative ways in front of the mirror, movements I had learnt from television and spying on women, women who were older than I was, and I even looked at my own genitalia with the eyes of another, judging myself, thinking, yes, this is good and yes, this is a woman.

The house I grew up in was a house of foreignness. My father was a translator and my mother was a bitch. Our house was filled with books with thick spines and golden lettering, some of which I ran my fingers up and down on.

I would tell my mother of the boys I was in love with and she would sit at the kitchen table peeling various fruits – apples, pears, oranges, blood oranges, kiwis – with a small but sturdy knife and she would always lean into the chair and slouch so her legs were spread and she looked dirty and sluttish.

Mother, I love Brian. Brian had ginger hair and ginger freckles and according to the children at school, he wore the clothes of other, dead children.

Mother I love David. David had webbed feet and, we thought, but perhaps incorrectly, rickets.

Mother, what I love about Mark is his passion for milk. His passion for bugs and small animals, his tender hands and foppish ways.

Of course, she dismissed all of these boys with the wave of a fruit-drenched hand.

Your father, now there is a man.

He translates the words of dead languages so we can understand them. He translates the languages of savages so we can understand the savages better. He translates the languages of foreigners, so we can get on well with the foreigners and not kill them, or they us, over a misunderstanding. Your father talks and I listen because he is a man of respect and good bone structure.

I walked away with my head down, defeated and my lungs pricked with a feeling I couldn’t quite put my finger on.

*

I gave my child away to science and left my lonely house.

At the time, I lived in the city and the memories of my husband, the cellist, were everywhere. I couldn’t walk past a park bench without thinking of him, about that time we kissed on it. The bench was dedicated to a Persian poet, and I noticed that every bench was named after the dead. I started to block out entire streets from my daily walks because we had both walked along those routes. Entire streets, benches, cafes, parks, everywhere, everywhere had become a series of places I couldn’t return to.

I decided that relationships are a series of places that you can’t return to.

And so with a pen and a map, I marked out where I could and couldn’t go. Entire sections of the map were marked red. I remember the streets that we walked down, hand in hand, he carrying a book on cellos, me carrying a freshly cooked sourdough. Other streets were erased because I thought of him there. Like the fountain behind that Georgian building, the fountain that was apparently the cause of a cholera outbreak and I saw a picture of a cholera victim, blue, sad, and thought of my husband. Even the cholera fountain had to go.

Life had become an act of whittling. Life before was like a large tree, I thought, for want of a better metaphor. And then, over time, I started cutting the branches off, chipping the bark, chipping it away, yes, and then chopping the top off to make the whole thing easier and then the shaving started, shaving it thinner and thinner until it became nothing at all and, in fact, to return to the reality of the situation, the map was all red, all except my house and then that was red too.

I couldn’t stay there. I went out and spoke to a group of local vagrants who sat in the alcove of an derelict building, soiled bed sheets, pots and pans, tins of food and I told them that my house was now their house. The vagrants moved in and I moved out.

*

I had infected our house.

Somebody did say I was infectious once, so perhaps it wasn’t farfetched to think that I’d made my house sick.

The sofa got the flu and sneezed up phlegm on my Persian rug. The lampshades got meningococcal septicemia and became covered in sores, red and black. The globe where I kept liquor got microcephaly and became so big I had to leave the room. My bed got cancer and didn’t accept me anymore. The wallpaper began to peel off the walls because it was depressed and, eventually, my microwave got dementia and forgot to cook the lasagna I’d put in it.

There was the sound of the cello, too. It wouldn’t go away. For each dream I had, there was a cellist creating the soundtrack to it; a slow, droning music that echoed in my head even after waking up.

*

I purchased an old farmhouse.

I went to the local landowner and purchased it with the money I’d found under the sofa.

The house was empty. The walls were bare and there wasn’t any furniture. There was a dead owl in the fireplace and I observed the majesty of its feathers before tossing it onto a homemade pyre.

One of the bedrooms was painted mustard yellow and another was painted the colour of vibrant ham.

The view outside my window reminded me of my dreams. If you want to know, there were trees, tall and thin, and some had leaves and some didn’t. The hills were round and lumpy.

For a while, I slept on the cold floor and wrapped myself in a small blanket that I’d found in what used to be a guinea pig hutch.

I remember the noises as if every living thing had been wired with a microphone to my brain. I could hear the blackbirds singing and the spiders crawling through the grass, every leg, and the sounds of foxes rutting, the pain of coitus, air.

*

And then the men started coming to the house, men with different bodies and different accents.

There were big men and small men, fat men and thin men. Men came with white skin and black skin. Some men had no skin at all. Skeletons. One of the men wore a fez, the other a fedora and a cigar. Another man came with a tape measure and insisted I measure him limbs, organs, circumferences.

The short men came in groups, for fear the taller men would wipe them out with their clubs hewn from strong forest wood. The taller men, too, were often wary of the packs of short men and had darting eyes.

There were the men with the big mouths whose stories of personal struggle could be heard over the treetops.

One man said: my mother loved me too much, which is why I’m so caring.

Another said: I was born in poverty and now I’m rich but no happier.

And also: I was born with a gift and this gift produces more life and wee.

The house that I bought was empty but thanks to these swathes of men the house was slowly filled with furniture, a plumbing system, paintings – usually their own portraits – carpets, paintings, pot bellied stoves, pet animals.

I smiled but didn’t ask for this. One of the men came up to me and said: So, what do you say? I said: What do you mean? And he looked at the hundreds of men surrounding the house, each holding a gift and he laughed and said what do you say to all of this? To which, of course, I said I don’t know. And, to which, of course, he replied: you were meant to say thank you.

*

Say these for me, baby. Say: hymen, uvula, rectum, scroll, pegbox, tailpiece, mongoloid, terratoma, syphilis, skin flap, epithelium.

Okay. For you, anything.

*

There they were, camped outside my house. They would come and knock on my door and ask how I was settling in.

Just fine, thank you.

A Tatar with a white hat danced a dance for me and handed me a puff pastry. Enjoy, he said and ran off into the forest where, undoubtedly, the other Tatars were camped and watching me with a collapsible telescope.

*

My body started to improve. My stretch marks magically disappeared or perhaps I just wasn’t looking at them; or that maybe people weren’t pointing them out anymore. And my feet had returned to their former size and no longer a point of ridicule amongst the men. My breasts were the same. My hair was no longer falling out and, again, maybe this was because there was none left to fall out. It all fell out over a number of years and left me with a shiny head and a penchant for purchasing wigs.

*

There was no sex, although the men offered to move into my vagina as if it were a house. Can we move in, they said. It’s cold out here and probably much warmer in there.

I said no. This house is not for sale. It’s not up for rent, either. In fact, this house is abandoned and empty. There’s a box of toys in the house and they’re from a time before we were born and over the box is a muslin cloth and nobody’s touched these toys in years.

*

My body wasn’t my body but a film. My eyes were cameras, 35mm cameras, and looking at my hands I thought: these are not my hands, but a moving image of what my hands look like. The same for my face in the mirror; it was like the first person had become the third person.

There she is.

There it is.

It’s not happy.

And this continued for some time. I became a character in the house and watched a life unfold.

I watched, as it was cooked dinner by other men. I watched it receive kisses in locked bedrooms and saw it getting undressed, positioned carefully by the bedroom window with the lamp illuminating just enough of its body – the curve of its back, buttocks, a nape – so the men camped outside could watch.

It was a body with an audience with perfect grammar.

*

The men complained of injuries, others of grievances suffered throughout their lives.

I broke a toe, one said.

My wife left me for a younger man who looks the same as me, but if better in almost every single way.

My wife left me for herself, who she said was better than I could ever be.

I became tired of listening to the men. I had listened to my husband for ten years. I listened to other boyfriends for years, too. I tried to think of how many hours I’d spent listening to men and created a pie chart in my head illustrating the ratio of time spent enjoying my life and time spent listening to men.

I thought of all the men who had used me for various things in their life: for talking at; for sex; as a punch bag. Looking at childhood photographs, it is interesting to see vitality in my eyes. Now, however, you could say some bulbs had blown in my vessel. I was tainted. I’d been handed around too many times. I was like an object that once had vibrancy but over time and with wear and tear had become dulled, blunted and ultimately nothing.

When all the men had gone to sleep and my doors were locked, double and triple locked, I sat in my bedroom with the lights off. Out there were the dying embers of the men’s fires and I could just about make out their eyes, open and staring back at me.

No matter where I go or where I travel, those eyes will be staring at me and their fires will not die out.

*

Sometimes the men danced. They danced into the night and made whooping noises. Some men got undressed. It was usually the fatter men who did this and their buttocks looked like battered pillows.

The men would become drunk and haunted in their eyes. Sometimes they’d storm the house but thankfully they provided me with barricades only hours before in case of such an emergency.

*

My breasts can fit several pens underneath them. I don’t need a penholder. And then my feet; my husband said they were large – even larger when the baby was on its way. Look at the size of these, he’d say and I’d say nothing. I’d smile a big wide smile that was fake and looked like I needed the toilet. He used to turn me over and investigate me. Look at this, he’d say. A prod. Look. And it was a spot on my spine. How does a woman get spots on her back? I don’t know I said and I was still smiling even though it wasn’t really a smile. How does a woman get a spot on her back? And here too. He prodded just above my anus, which was unshaven and shabby – his words, not mine – and there was a spot there too. I was covered in spots. He said I was a shipwreck again and again and that my body was sinking treasure. I smiled and smiled and smiled.

Learn things too, he said. I play the cello, what do you do? I read. He said learn this, learn that. I did. I learnt about burn marks on bodies. I learnt about plastic surgery techniques and how people learnt to use prosthetic fingers after having them crushed. I learnt things for him. I learnt the cello. I learnt about castrato singers. I was a fountain of knowledge and full of beans. His words not mine.

*

In fact, the act of swallowing had become a problem, which we shan’t get into but I basically had to count to three before swallowing, like taking a leap of faith, and only then did the water or soup go down my throat.

The men had no problem eating and I watched them, jealously, as they skinned rabbits, cooked rabbits and ate rabbits. The men were constantly fat with gin and here I was in the house alone, counting to three and creating new superstitions and new rules to impose upon myself, as if I couldn’t sink any lower.

*

The men now reside in my house and my body and when I talk they tell me to be quiet and be beautiful and they tell me my faults and I smile and I sink to the bottom of the ocean and they watch my shipwreck surrounded by sand and seaweed and sharp, jagged rocks. They stroke my hair and I say nothing and sometimes I purr because they tell me to. Their eyes search for my treasure but their eyes are tired, but I know their eyes will not stop looking at my shipwreck, that their eyes will not die and I think of the quicksand and, yes, that maybe I should sink. All their language became foreign the lower I sank. My ears would fill with liquid and all I heard were the languages of savages, foreigners, sounds.

*

I remember when I first met my husband, the cellist. It was in a café. People sat in the café facing each other and, perhaps, staring through each other at other cafés, thousands of miles away where the exact same action was occurring.

We also sat staring at each other. We’d met outside. So perhaps it’s safe to say we didn’t meet inside the café, but outside the café. Now we were inside and two black coffees sat beneath our chins.

I went to talk but he was first and said let me tell you about life and pain.

I smiled.

And then I said, okay and listened.